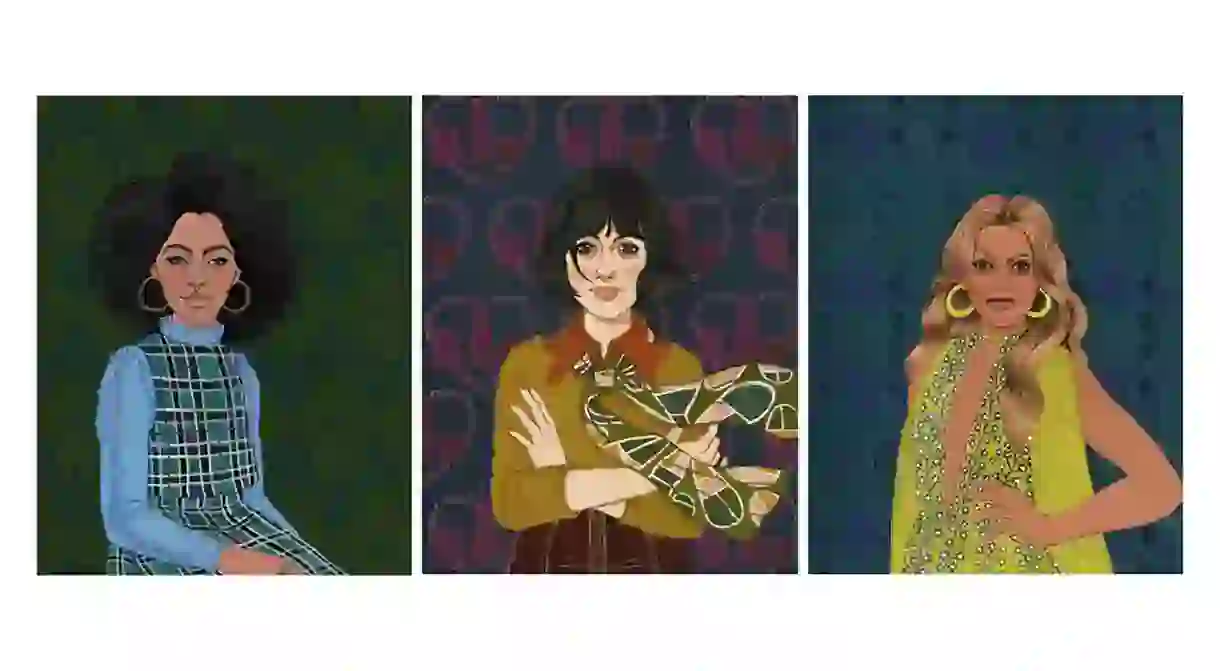

The Renegade Queens of American Screens

Elizabeth Weitzman’s newly published book Renegade Women in Film & TV profiles the movers and shakers who have disrupted a male-dominated industry. Here, the New York film critic and author takes Culture Trip through 100 years of both setbacks and progress.

Culture Trip: Your book explains that while there were opportunities for women directors in early Hollywood, once the studio system solidified, as you put it, pioneers like Lois Weber and Dorothy Arzner suffered badly. It’s as if the studios closed ranks against them.

Elizabeth Weitzman: As soon as it became clear that this was an industry in which there was real money to be made, women were shut out in often heartbreaking ways. Lois Weber was hugely famous, but her career ended in a very sad way. Women filmmakers were also shut out by film historians, so it’s important to restore them to the history of film.

CT: In the ’30s and ’40s, melodramas were tailored to female moviegoers. Why wasn’t it recognized that women could make these films as well as, or better than, men?

EW: It’s understandable that the people in power would want to keep the power. Dorothy Arzner, who was the only prominent female filmmaker in the ’30s, made women’s pictures, but in a completely different way to male directors. Her movie Craig’s Wife [1936], written by Mary C McCall Jr – another formidable woman in Hollywood – stars Rosalind Russell as a woman whose life is defined by her position as a homemaker and a wife. The play on which it was based is very cool to the heroine, but when Arzner and McCall reconfigured the story, it became an indictment of a society that gives women no option but to aspire to being a perfect homemaker.

CT: Which of the women you wrote about surprised you the most?

EW: Alla Nazimova, who in the late 1910s and early ’20s was one of the most famous and highly paid actors in America, male or female. She was also an openly feminist, Jewish queer immigrant, whose story we should all know today. She was so ahead of her time that she pushed things too far. She produced and starred in an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé [1923], an avant-garde work of early queer cinema, radical in its artistry, which audiences were not remotely ready for. She also created a hedonistic community at her Hollywood mansion, the Garden of Alla. And she hosted ‘the Sewing Circle’, a group of gay and bisexual women who couldn’t be themselves in public because they had to protect their images. Eventually her backers withdrew their support and Nazimova couldn’t make films any more. She returned to Broadway, the site of her first success in America, and was acclaimed for her stage work again.

CT: New York seems more receptive than Hollywood to talented women like Nazimova, Mae West, Barbra Streisand, Elaine May, and the remarkable Gertrude Berg, who wrote and starred in The Goldbergs [1929-46] radio serial. She brought it to Broadway and TV, and there was even a film. As a story of a Jewish family, it’s a precursor of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.

EW: So much TV can be traced back to Gertrude Berg, who created the first successful family sitcom. When I started researching the book, I found that many women who faced a closed door in Hollywood went into TV – and really pioneered it. Lucille Ball and Ida Lupino are great examples of that. From 1949 to 1953, Lupino was the only female director working in Hollywood, but after that she directed almost exclusively for TV. The women directors Ava DuVernay hires to film episodes of her series Queen Sugar should all be working in film constantly, but it’s great that she’s created an amazing arena for their work.

CT: Critics rave about the New American Cinema of the ’70s, but it didn’t benefit women.

EW: Everyone talks about the ’70s as this golden era of filmmaking, but it only was for men. The critic Molly Haskell showed us in her book From Reverence to Rape how badly women were portrayed on screen at that time: as mothers, wives, girlfriends, prostitutes and neurotics. Take Diary of a Mad Housewife [1970]. The only woman making mainstream films then was Elaine May. It wasn’t easy for women in TV either, but Mary Tyler Moore made a real breakthrough playing a woman who turns her back on the marriage-and-motherhood ideal to become a career woman – a TV news producer – with a romantic life on The Mary Tyler Moore Show [1970-77]. That show addressed women’s issues in ways that weren’t being addressed on the big screen.

CT: The ’70s and ’80s saw the emergence of directors like Barbara Kopple, Joan Micklin Silver, Kathryn Bigelow, and Susan Seidelman, and the advent of indie cinema in the ’80s also gave women filmmakers a boost. The door opened.

EW: I would say it cracked open. Barbra Streisand had a lot to do with that when she directed Yentl [1983] after trying to get it made for 16 years. She also co-wrote, produced and starred in it and became the only woman so far to win the Golden Globe for Best Director, which is kind of crazy.

CT: In your interview with Molly Haskell, she says, “We may be looking at a genuine turning point, even a massive one” for women filmmakers today. Have #MeToo and Time’s Up had a positive influence on gender parity in film and TV?

EW: Absolutely. Opportunities for women are occurring in ways they never have done before. And the more women work in the industry, the more will do in the future, because women support each other. This has been the case from the beginning. Alice Guy-Blaché, the first woman director, helped Lois Weber get her start. Then Weber mentored Frances Marion, who wrote films for Mary Pickford and helped Lois Weber after her career had collapsed.

CT: What are your favorite New York movie theaters where people can go and see films by and about women?

EW: Anthology Film Archives has great series celebrating female filmmakers. The programming at Metrograph and Film Forum frequently includes female filmmakers. Yesterday, I took my daughter to see Elaine May’s Ishtar at Film Forum – I’m glad she saw it in such an amazing theater. We also go to Alamo and Nighthawk in Brooklyn.

CT: If there’s a place in New York that represents progress for women in the industry, it’s 30 Rockefeller Center, home of Saturday Night Live.

EW: SNL has always made a place for women in entertainment, but it was much more of a struggle in the early years. Gilda Radner was always an icon, but Jane Curtin has never shied away from talking about how difficult it was. Tina Fey and Amy Poehler and their generation said, “We deserve to be here.” And they were so brilliant and funny that everyone accepted that.

CT: Your book profiles these amazing women in a roughly chronological order. It must be significant that you end with four African-Americans: Shonda Rhimes, Laverne Cox, Ava DuVernay and Jessica Williams.

EW: There are not as many women of color in the first chapters because few were working, sadly. But how wonderful that women who represent so many different elements of entertainment today also represent an incredible diversity of experience and voices.

Renegade Women in Film & TV, published by Clarkson Potter, is available from Amazon.