Meet Grant Achatz, America’s Most Creative Chef

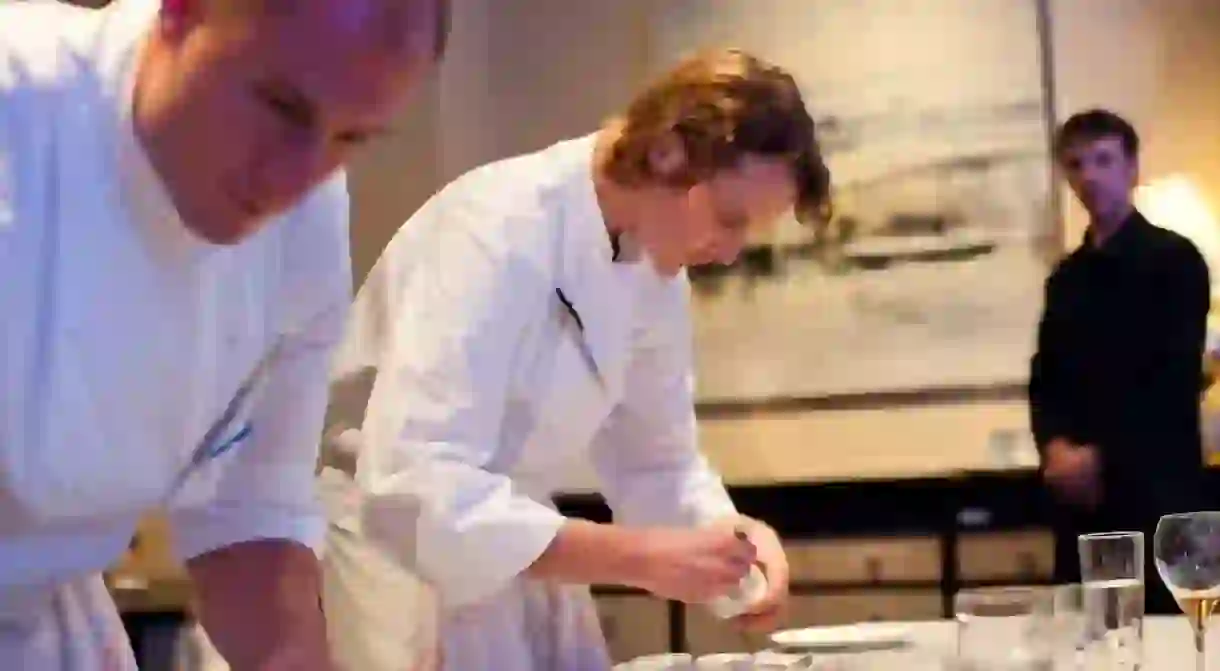

Grant Achatz, the chef of Alinea and several other Chicago restaurants, as well as two new bars in NYC, dazzles diners with his innovative approach to food and drinks.

It might seem a cliché to say that Grant Achatz, the Chicago-based chef of Alinea, Next, The Aviary and The Office, and Roister, is as much an artist as he is a chef. But it’s a more accurate statement applied to him than to perhaps any other chef alive today: He gets plating inspiration from art museums; his primary motivations are pushing boundaries and eliciting emotions—notions you hear about much more often in the art world than when talking about restaurants.

It might be equally tempting, though, to say he’s even closer to a magician—surprising and astounding and upending his guests’ expectations. In his drive to question his own assumptions about food, he wants to make his diners do the same.

In the dozen years since Alinea, Achatz’s first restaurant, opened, he’s become known as one of the leaders of the molecular gastronomy movement in America. (Although he hates that term; he prefers to say “progressive American.”) Whatever you call it, he’s using science to manipulate the flavors and textures of food in innovative and unexpected ways, and winning a whole lot of accolades along the way for his groundbreaking tasting menus. This, despite being told in 2007 that he had Stage IVb cancer of the tongue and likely had only a few months to live. Of course, he’s never been one to hew to expectations.

Beginnings

Achatz grew up in a restaurant family; his parents owned a diner in Michigan, and according to Achatz, he spent more time there than he did at his own house. By age five he was washing dishes there, and working as a line cook by age 12. He was making purely basic, utilitarian food, though; his parents discouraged even the simplest of garnishes. It wasn’t until he, at the goading of an uncle, ate a pickle wrapped around a bundle of French fries, that he fell in love with food—with the interplay of flavor elements (starch, fat, acid, salt). “It wasn’t about physical cooking,” Achatz says on Chef’s Table. “For me it was about curiosity. It was about toying with things.”

After graduating from the Culinary Institute of America, he spent an unhappy stint working for chef Charlie Trotter. He moved from there to the French Laundry, where he was dazzled by Thomas Keller, the head chef. Keller was similarly impressed by his protege’s drive, and sent him to do a brief spell at El Bulli, which was at that time the world’s leading molecular gastronomy restaurant. Achatz returned to the French Laundry inspired, perhaps a little too much so: His outlandishly creative ideas wouldn’t play in Keller’s more traditional kitchen. He felt stifled, and knew it was time to leave.

Achatz struck out for Chicago, taking the reins at a restaurant called Trio. There, he impressed a diner named Nick Kokonas, who offered to fund a restaurant should he ever want to go solo. He did.

Thus came Alinea, a mind-bending restaurant that gave Achatz the perfect outlet for his relentless creativity, a place for him to explore, invent, and play with food to his heart’s content, surrounded by like-minded people.

“Early on at Alinea, we had this realization that there’s other disciplines that we can draw on for inspiration,” says Achatz on Chef’s Table. He would take his team to art galleries and view huge pieces of art, and he was frustrated that as a chef, he was limited to a scale determined by plate manufacturers. He was full of questions: Why can’t you eat off of a tablecloth? Why do you need to use a fork or spoon, or serve a dish in a plate or bowl? Is there a better way to do things? He was determined to break—or, at the very least, question—every existing rule of dining.

#flashbackfriday to Strawberry, jasmine, basil, balsamic at Alinea #happyfriday #dessert #legos #helloweekend #alinea #foodandwine #chicagofood

A post shared by The Alinea Group (@thealineagroup) on Feb 26, 2016 at 3:06pm PST

“The leading chefs in the world know that they can make delicious food,” says Achatz on Chef’s Table. “So we have to take it a step further. At Alinea, we’re actually trying to curate an experience. I want the guest to have a sense of wonderment. ‘What’s going to happen next?’ They shouldn’t go, ‘I know what this is going to be like.’ They should expect the unexpected.”

From the very start, he aimed to make it the best restaurant in the world.

Success

He largely succeeded in that quest. Alinea opened in May of 2005. Notable critics like Frank Bruni and Ruth Reichl visited on opening night, and food-world fame followed near instantaneously. The accolades flowed in: Best Restaurant in America from Gourmet magazine, a near-immediate appearance on the World’s 50 Best list, and many more.

Sweet cicely, Sesame in gold, Chinese cinnamon (📷 @matthew.gilson )

A post shared by Grant Achatz (@grant_achatz) on Jul 22, 2016 at 2:08pm PDT

It is impossible to overstate how different Alinea is from what had ever come before. Merely entering the restaurant is disconcerting—an exercise in confusion and illumination and surrender. Those feelings only intensify throughout the meal. “The thing that’s important for me,” says Achatz on Chef’s Table, “is the guest has the ‘aha’ moment where they feel they’ve discovered something. It’s like being a kid and opening the present at Christmas: Until you lift that lid and peer inside, you don’t really know what’s in there. And then there’s the reveal. And then there’s the reward. It’s a magic show.”

He employs magicians’ tricks—sleight-of-hand and misdirection and even occasional levitation—to astonish guests. He disguises tasting menu courses as centerpieces. He hides foods within the preparations for other foods being served. He sends out floating edible balloons, and dishes resting on a cushion of fragranced air that puffs out as you eat. Dishes might be billowing with smoke, or suspended from a wire, or “spray-painted” with sauce at the table. His kitchen might create something that looks like a strawberry but tastes like a tomato, or vice versa. “It’s a fun dynamic: to be able to surprise people with food,” Achatz says. “That’s always the thing for us: At every turn there’s a little twist.”

Happy 11th Birthday, Alinea! #windbackwednesday to the signature balloon, helium, green apple. #alinea #happybirthday #balloon #greenapple #celebrate #chicagofood

A post shared by The Alinea Group (@thealineagroup) on May 4, 2016 at 3:20pm PDT

And his techniques employ science, to be sure—all the usual tricks of molecular gastronomy. But ultimately, Achatz is creating art. Back to that pillow of scented air, for example. Aroma has always been incredibly important to him. Nothing is more effective than scent at evoking memories, and harnessing and capturing that ability is another tool he employs in curating a dining experience. “We treat the emotional component of cooking food as a seasoning. You add salt, you add sugar, you add vinegar, you add nostalgia,” he says. “If you’re able to move people, we’re moving on to something else—it’s not just about food; it’s not just about a restaurant or eating dinner. It’s about something more.”

Illness

Not all was well during that time, however. In 2004, while he was still at Trio, he started to be bothered by what he initially took to be a canker sore on his tongue. He made an appointment with a dentist, who told him he was likely biting his tongue because of stress. As he developed Alinea he continued to be bothered by it; the spot grew and worsened. By early 2007, the white bump had grown into full-on tumor. He saw an oral surgeon and was told he had tongue cancer—Stage IVb, basically as bad as it gets. To put it another way, there is no Stage V. He was told that surgeons would need to amputate most of his tongue, much of his jaw, and both sides of his neck…and even then, there was still a 70% chance he’d die within a few months.

This is a tragic enough prognosis for anyone. But for a chef, who makes his living off of his sense of taste, it’s catastrophic. “How can you be a chef, how can you cook, and not be able to taste?” he asks on Chef’s Table. Achatz told Kokonas that he would prefer to die gracefully, forgoing treatment.

Achatz and Kokonas decided to make an official public announcement about his illness; they figured word would get out soon enough anyhow. After hearing of Achatz’s predicament, doctors from the University of Chicago reached out; after a consultation, Achatz was offered an experimental, more conservative, treatment that would allow him to keep his tongue and jaw. Plus, these doctors gave him a 70% chance of survival with this treatment regimen, flipping the odds he’d been given before. Achatz decided to give it a go.

@grant_achatz – #alinea #chicago #chefstable #bookings #continuallyevolving (📷: @matthew.gilson)

A post shared by The Alinea Group (@thealineagroup) on May 27, 2016 at 12:55pm PDT

The University of Chicago treatment involved 12 weeks of chemotherapy, during which Achatz continued working long hours at Alinea, a grueling schedule. He also received six weeks of radiation targeting the area from the tip of his nose to his collarbone. Soon after the radiation started, Achatz noticed that foods began to taste strange. Within a week, he’d lost his sense of taste entirely, and doctors couldn’t tell him whether he’d ever regain it. This isn’t something he’d been warned would happen. He was suddenly thrust into the uncomfortable position of having to create food that he could not taste.

He continued to cook during this entire time, relying on other senses—smell, of course, and even sight, as well as his memories of flavors—to guide him. And simply continuing to serve existing dishes wasn’t an option for him; his raison d’etre is consistently creating, inventing, changing up the menu entirely every few months. It invites an obvious comparison with Beethoven, who continued to compose even after he’d gone deaf. A writer from The New Yorker mentioned it during an interview with Achatz during that time, whose reaction was grim. “Achatz answered, his hoarse voice rising, ‘[Beethoven] did it, but did he enjoy it? Sure, he wrote a great symphony when he couldn’t hear. I can cook right now and I can’t taste. So I enjoy it on a mental level. But do I wish I could taste my own creation and be satisfied with it? Sure I do.’”

Achatz felt the need to keep demonstrating that he, and the restaurant, were still innovating. He worked out new ways to communicate to his cooks what new dishes should taste like. He also realized, for the first time, that he couldn’t do everything alone; he needed to relinquish some control in his kitchen.

@dan_perretta ‘s @aviarycocktails course of Maitake mushrooms,Perigord black truffle, concord grape and hazelnut. #cocktails #theaviary

A post shared by Grant Achatz (@grant_achatz) on Jun 20, 2017 at 5:45pm PDT

“I honestly think him being sick taught him how to be a chef,” Dave Beran, who worked at Alinea during that time, says on Chef’s Table. He says that previously, Achatz had felt he needed to do everything himself, even plating a new dish for the first week or two weeks before he’d allow anyone else to do so. “Now, he’s creating food without ever touching it.”

Recovery and new beginnings

By the end of 2007, Achatz was declared entirely cancer-free. A short time later, he noticed he could taste sugar; his tastebuds were starting to return. Salt returned about a month later. Flavors came back to him in waves. He was essentially experiencing a baby’s taste development…as a 33-year-old. It was revelatory to him. “I was on fire with an amount of energy that I think I’ve never had before,” he says on Chef’s Table. “because I got a second chance and I didn’t want to screw it up.”

He threw himself into his work more deeply than ever. In 2008, he was awarded the James Beard Award for Outstanding Chef. In 2011, the team opened Next, a tasting-menu restaurant whose menu—and entire concept—changes completely every few months; it received the James Beard award for Best New Restaurant the following year.

Also in 2011, Achatz and Kokonas opened The Aviary, and its companion “speakeasy,” The Office. The focus at both is on cocktails; uber-modern The Aviary employs techniques developed at Alinea but applies them to drinks. Remember those pillows of scented air? You’ll find them here, too—perhaps a whiskey-based cocktail delivered in a smoke-filled bag that releases aromas of sandalwood with each sip.

The “Wake and Bake” by @micahmelton For the Aviary NYC. Many people have been asking us how the NYC Aviary will differ from Chicago. This is a good example of how we have nudged the food and drink based on the new location. The drink: Aviary Selected Mississippi River Distilling Company Rye, Coffee & Orange Infused Vermouth, Coffee Liquor, Everything Bagel Aroma. Basically a NYC breakfast infused Manhattan. The wake part of the name is easily disciphered, the bake part is from the use of the volcano vaporizer used to fill the bag full of aroma. Well played @micahmelton #cocktailnames 📷@ahemberger

A post shared by Grant Achatz (@grant_achatz) on Sep 16, 2017 at 10:22am PDT

Alinea currently holds three Michelin stars and a seemingly permanent spot on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list. Nevertheless, Achatz and Kokonas closed the restaurant for several months last year to do an extensive renovation, for no reason other than to keep changing things up to move forward, they say.

The team also continues to expand their restaurant empire. During their renovation of Alinea, they also opened Roister, a more casual concept that’s already earned its first Michelin star. Earlier this summer, they opened a sister location of The Office in NYC, high up in the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Columbus Circle, and are on the cusp of opening the NYC location of The Aviary adjacent to it.

“There’s a need to feel alive in anybody, and the way that it works for Grant is that he works at something, works at something, works at something, creates it, he goes, Oh, now I need to go do something radically different,” says Kokonas on Chef’s Table. “And ‘new’ is a way of feeling like he’s propelling himself forward.” We can’t wait to hear what’s next for the team.

Opening Night… again! #theaviarynyc

A post shared by Nick Kokonas (@nkokonas) on Sep 27, 2017 at 1:31pm PDT