A Street In Bronzeville: A Glimpse From Gwendolyn Brooks’ Window

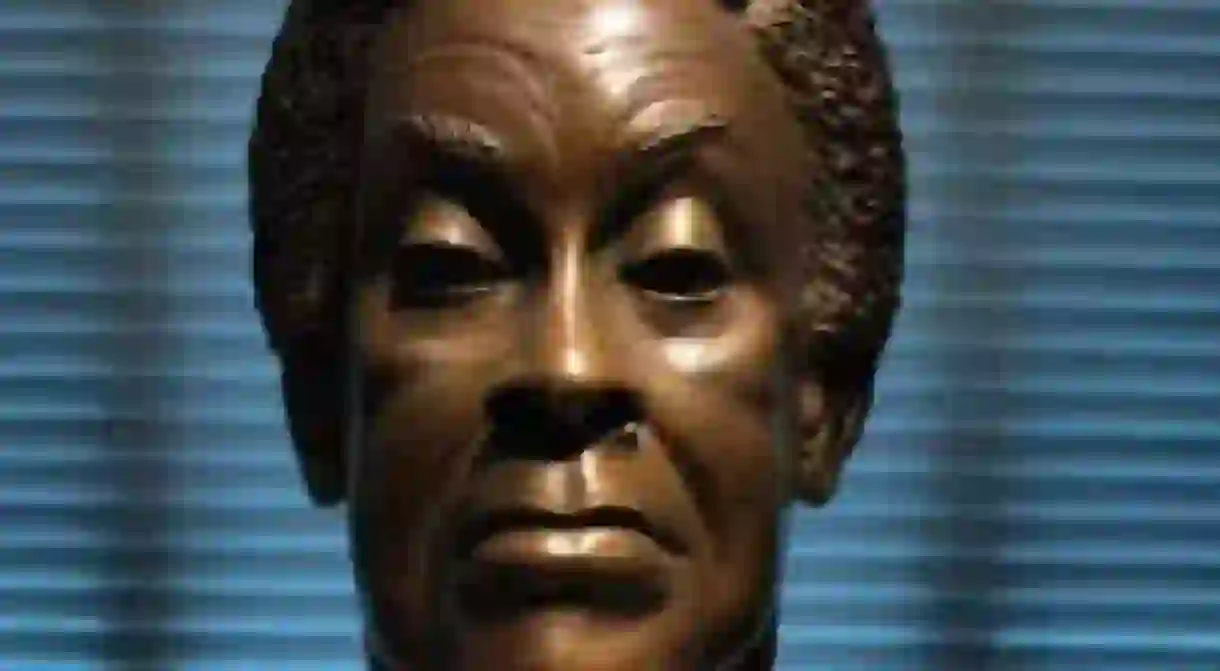

Born in Kansas and raised in Chicago, Gwendolyn Brooks was the first black author to win a Pulitzer Prize (1950). Discover how Chicago was at the heart of her poetry and what made her a prominent figure in the 20th century.

Chicago has been home to many great novelists such as Ernest Hemingway and Lyman Frank Baum, but not all of them used the city as an inspiration in the way that poet Gwendolyn Brooks did. Using the city’s South Side as a backdrop, Brooks published her poetry collection A Street in Bronzeville in 1945, which brought her fame.

Born in Topeka, Kansas in 1917, her family moved to Chicago when she was only six weeks old. In Chicago, Brooks attended three different high schools: Hyde Park High School, the predominantly black Wendell Phillips Academy High School and the integrated Englewood High School. The different racial prejudices found within each school greatly influenced Brooks’ understanding of social and racial dynamics.

It was this setting that helped the poet create memorable characters. Brooks would be the first to admit it, as she did during an interview with Black Issues In Higher Education. She claimed that her writing would not have been the same had she grown up in Kansas and was thankful that her parents decided to move to Chicago: ‘I am an organic Chicagoan. Living there has given me a multiplicity of characters to aspire for. I hope to live there the rest of my days.’

Brooks discovered her love for writing at a young age. She was first published at the age of 13 in American Childhood Magazine and kept writing ever since. Later in life, Brooks is known to have said, ‘I felt that I had to write. Even if I had never been published, I knew that I would go on writing.’

Meeting Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson shortly after being published, Brooks was determined to keep writing since both authors encouraged her to write regularly and read T.S. Eliot and modern poetry.

However, it was from Inez Stark Boulton that Brooks learned Modernist poetry in the early 1940s. The upper-class Chicagoan held a poetry workshop in the South Side’s Community Art Center, which Brooks attended regularly. This exposure would explain why her poems are a mixture between black folk poetry and modernism.

In 1950, Brooks published Annie Allen, which chronicles a black girl growing into adulthood, for which she received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. This marked her as the first black (the term she preferred over African-American) woman to receive the award. This was only the beginning of her accolades. In 1962, Brooks was invited to read at a Library of Congress poetry festival, and in 1968, she became the Poet Laureate of Illinois. She also received the honor of being Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985.

The late 1960s marked a turning point in the poet’s life since it led to her awakening as a leader in the Black Arts Movement. She moved away from leading publishing houses and toward black publishers like Broadside Press. Her poetry also underwent a slight change; it focused on free verse and was more concerned with social issues.

Gwendolyn Brooks was an active laureate until she passed. She participated in multiple public readings, taught at a multitude of colleges like University of Wisconsin, and, perhaps more importantly, kept encouraging young writers to voice their thoughts through poetry. Ever the Chicagoan, Brooks organized poetry activities for the underserved children of Chicago. In the end, Brooks’ wish came true; she lived in Chicago for the rest of her days, faithful to her home in the South Side, and passed away from cancer on December 3, 2000.

A closer look at Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry:

The Pulitzer Prize winner’s bibliography boasts of 36 published works. What connects all of her writings together, said Professor Maria K. Mootry, is the respect for modernist aesthetics of art and principles of social justice.

A Street in Bronzeville was the compilation that brought fame to Brooks. In this collection, you can see how she uses a variety of poetic forms to bring her characters to life. Brooks goes from ballads to urban blues poems to sonnets to Chaucerian stanzas, and it is in this great mixture of forms that you see how Brooks synthesized all of her influences into her own voice. Her titles can be found in the lower case like E.E. Cummings, some poems have a flair for the dramatic as seen in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry, and others remind you of Langston Hughes’ jazz.

Although different in form, the poems in her collection all share the same idea. As Mootry put it, the compilation tells the stories of poetic characters, their struggles, their small triumphs and ultimately their unheroic survival. Brooks once told historian Paul M. Angle that she ‘wrote about what I saw and heard in the street. I lived in a small second-floor apartment at the corner, and I could look first on one side and then the other. There was my material.’ As you read the poems, you can imagine that is exactly what happened — Brooks was simply soaking in life around her because the poetic subject appears to be simply reporting the facts as life goes on in Bronzeville, the name which represents the entirety of Chicago’s South Side.

While some of her poems may appear to be written at a casual level, that shouldn’t be mistaken for simplicity. For example, in A Street in Bronzeville, she writes a powerful anti-abortion piece titled ‘the mother’ that is easy to understand, but the casual reader of Gwendolyn Brooks should be made aware that the bulk of her poetry is actually complex. For instance, her mock epic poem ‘The Anniad,’ found in Annie Allen, is divided into 43 stanzas plus appendix poems that are riddled with sexual politics.

Brooks’ poems reveal to the reader an ugly world filled with violence. Fratricide is discussed in ‘the murder,’ prostitution in ‘My Little ‘bout-town Gal’ and ‘The Lovers of the Poor’ satirizes those who pretend to be charitable. Yet her mastery over language and poetic techniques and her growing dedication to social justice make her poetry an illuminating read.