We Spoke to Memoirist Lou Cove About His Childhood Friendship With a Playgirl Model

The author of Man of the Year talked to us about coming of age in the late 70s, the fruitfulness of unorthodox friendships, and Playgirl‘s impact on America.

While it may seem odd to consider it as such, Playgirl, the erotic magazine for women, was at one point one of the most progressive cultural magazines of its time. Founded in 1973 during the rise of the 1970s feminist movement, its founder Doug Lampert reversed the conventions of pornography by selling images of the male body to a female audience. When Ira Ritter took over the magazine four years after its founding, he emboldened its mission to service not just hetero women’s sexual desires (and, indirectly, gay men as well), but to create a space where issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, and feminism could be openly discussed.

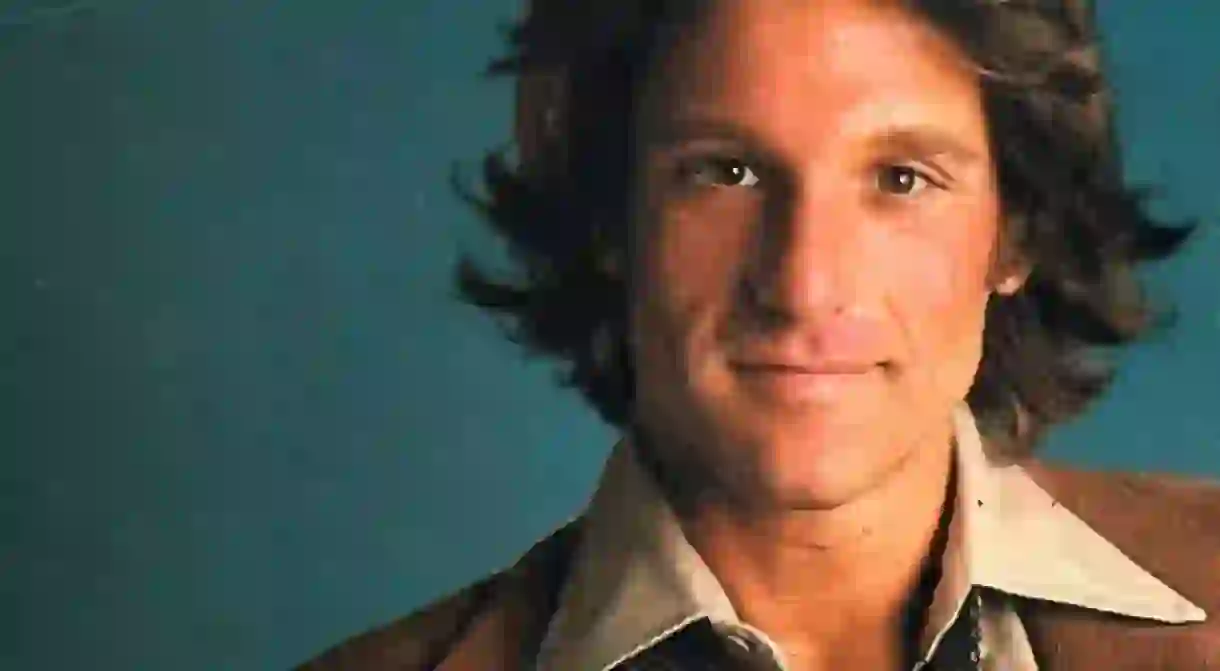

Playgirl, at least in its early years, also helped to liberate the lower torso of the male body from its upper half. Because many of its models appeared in its pages “full frontal” Playgirl models doubled as spokesman for the sexual revolution, particularly the publicized winners of the magazine’s coveted “Man of the Year” award, which highlighted the best of the magazines annual monthly models. In 1979, that honor went to a young film actor and pornography actor named Howie Gordon. To get earn that title, Howie didn’t just pose pretty, he launched a campaign and enlisted a boy named Lou Cove to be his manager.

Nearly 40 years later, Cove has published a memoir of that account. Then barely a high schooler, Cove had moved from New York City to Salem, Massachusetts and was ever the new kid in town when Howie, an old friend of his father’s, came to live with Cove’s parents, bringing along his new wife Carly. His family and social life being less than stellar, Cove took to Howie as both a favorite uncle and best friend, helping to see Howie to victory while the model served as a liberator to Cove’s troubled home life.

We spoke to Cove about coming of age in the late 70s, the impact Howie Gordon had on his life, and how Playgirl foresaw the liberal / conservative culture wars that divide America today.

Man of the Year is set just after you’ve moved from New York City to Salem, Massachusetts, and you paint a great portrait that town circa 1978. But could you talk a bit more about the city you left behind? What did you miss about New York when you moved to Salem? And what about that town felt alien to you?

New York City is like Wonka’s Chocolate Factory when you’re 9, 10, 11…you had magicians and bubblegum blowing contests in Central Park. The Empire State and Chrysler buildings watching over you. Smoked fish, cheese, and babka at Zabar’s (where my family made a pilgrimage every weekend instead of going to synagogue). And there was such an amazing diversity of people in the city at that time. It was impossible to feel like an Other, because everyone was Other. At precisely that age when you don’t want to feel different, you didn’t have to in New York.

By contrast, Salem was a place where everyone conformed and outsiders stuck out like a sore thumb. It’s not a coincidence that this is Scarlet Letter land. Being a New York Jew with long hair and ripped jeans immediately set me apart from the townies. Ironically, you could be a witch in Salem and not be given much of a hard time in the 70s. But aside from that exception, it was status quo or go.

The book is propelled by Howie Gordon, who is invited by your father to stay with your family almost as soon as your family itself has moved to Salem. Before he moved in, what was his relationship to your family like? How much do you feel you owe your coming of age to him?

Howie was a former intern of my dad’s. They worked together for the War on Poverty in the late 60s and early 70s. Howie had flitted in and out of our lives over the years, so he was vaguely familiar to me. He’s ten years my dad’s junior, but they were always very close and my father treated him like a younger brother. That said, I didn’t really get to know him until he and his wife, Carly, ended up living in our house for 12 months. My mother was — and still is — completely charmed by Howie. She also developed a deep friendship with Carly. So their presence in our lives has always been a positive thing.

But my father helped me to come of age. He was there for most of it. But if anyone came in second it would be Howie. Particularly since the example he set, and the ways in which he exhibited his masculinity (not just on the pages of Playgirl) were radically different from my father’s. Where my dad was stiff-lipped and tough, Howie was shockingly honest and vulnerable. Where my father chose to make a clear distinction between adults and children and how we should engage, Howie followed no such boundaries. The result, playing Hutch to his Starsky, was that Howie made me feel as if I had already come of age. We were a team. At least that was the way it felt at the time. So I certainly thought he had taught me everything I needed to know to be a man. But there were still a few lessons yet to learn!

Howie also brings his new wife Carly to stay with your family. She remains a bit in the background throughout the book, but did she grow close to your sister or your mother? What was that relationship like?

Carly was the kind of person that could make strangers feel comfortable opening up about topics that were in that era totally taboo. Carly developed a therapy practice built around discussion groups in which women would come to our living room and engage in honest conversations about intimacy and sexuality. Anyone who can do that successfully has a gift — a way with people that makes them feel safe and heard. So her effect on my mother and sister, two people who were wrestling with their own kinds of repression and fears, was profound.

Carly also demonstrated a powerful ability to express love and joy in a way that my family, although extroverted, did not come close to. She brought out the best in all of us. My sister, being only nine, experienced Howie and Carly as colorful, sensational, surprising roommates— the extraterrestrial hippie aunt and uncle sleeping in the room next door. I don’t think their presence informed her coming of age in the way it did mine, but it cemented a relationship and an affection that has lasted throughout for both her and my mother. In fact, Howie and Carly are coming to visit all of us this coming Thursday for a week. Or perhaps it will be longer…

Howie recruited you on his quest to become Playgirl‘s “Man of the Year” which later in the book, you realize is an idea that mainstream America hasn’t quite warmed up to. Even Donahue, whose show Howie appears on, ridicules him on air. In a sense, it foreshadows the liberal vs conservative culture wars the America is engaged with today. Do you see it that way?

The irony is this: compared to what my teenage kids can find with a quick Google search today, what was turning Phil Donahue’s hair white back then was so incredibly tame. On the one hand, Playgirl magazine had as many as two million subscribers in the late-70s, making it a major national magazine, even if people didn’t admit they were reading it. So it was already mainstream, at least by the numbers. But that doesn’t mean that Middle America was comfortable with it, and Phil Donahue, whose show was based in Chicago, had his finger on the pulse of that more conservative center. Looking back at the video of that interview, you can certainly see where the cultural fault-lines are. Some folks are titillated, while others are absolutely scandalized. The difference today is just how shrill the opposing sides have become. The great thing about Donahue was that he curated a national dialogue. These days, everything in the media feels like either an echo chamber or gladiatorial combat.

Man of the Year is your debut book. How long did you spend writing it? How has it been to see it out in the world? And has it prompted you to work on another book?

Once I was clear about the story I wanted to tell, the writing went relatively fast. It took me approximately ten months to complete a first draft of the memoir, which was written in the past tense. Just seemed like that’s the way one should do it. But when I came back to the manuscript I didn’t feel the immediacy of those adventures the way I did in my memory. So I rewrote the entire book in the present tense. And that took some time.

As for the reception: There’s no greater thrill than seeing a book you’ve written in the window of a bookstore you have frequented. Good reviews are icing on the cake — that’s beyond any expectation I had when I was working on this story. I just wanted to get it out into the world. But reading to audiences and hearing from readers who have found something universal in my particular tale has been the best. Whether it’s rediscovering an obscure 70s song, having an unconventional upbringing, or recalling a crazy character that helped make you who you are — those connections are the most deeply gratifying.

So, hell yeah I want to write another book. I’m in the research phase now, so all I can say for the moment is that a minor character in Man of The Year will make a major appearance in the next one.