Legendary Artist and 'LOVE' Sculptor Robert Indiana Dies at 89

Famed artist Robert Indiana, who garnered international acclaim for his iconic LOVE paintings and sculptures, died of respiratory failure at his home off the coast of Maine on Saturday, May 19.

Born Robert Clark in 1928, American artist Robert Indiana—who hailed from New Castle, Indiana—is best known for creating one of the world’s most beloved images.

Yet Indiana’s practice began long before, and continued long after, LOVE.

The artist worked across disciplines as a prolific painter and sculptor. He began experimenting with art in the 1940s through a series of figurative and landscape pieces executed in gouache, watercolor, and graphite; and following three years of military service, Indiana enrolled in The Art Institute of Chicago from 1949 through 1953. He spent a summer at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, and then a year in Scotland at the Edinburgh College of Art. In 1954, he settled in New York City with an initial focus in poetry.

It was in New York that Indiana would cross paths with Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, and Cy Twombly, all of whom worked within—and helped cultivate—the spheres of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and color-field painting.

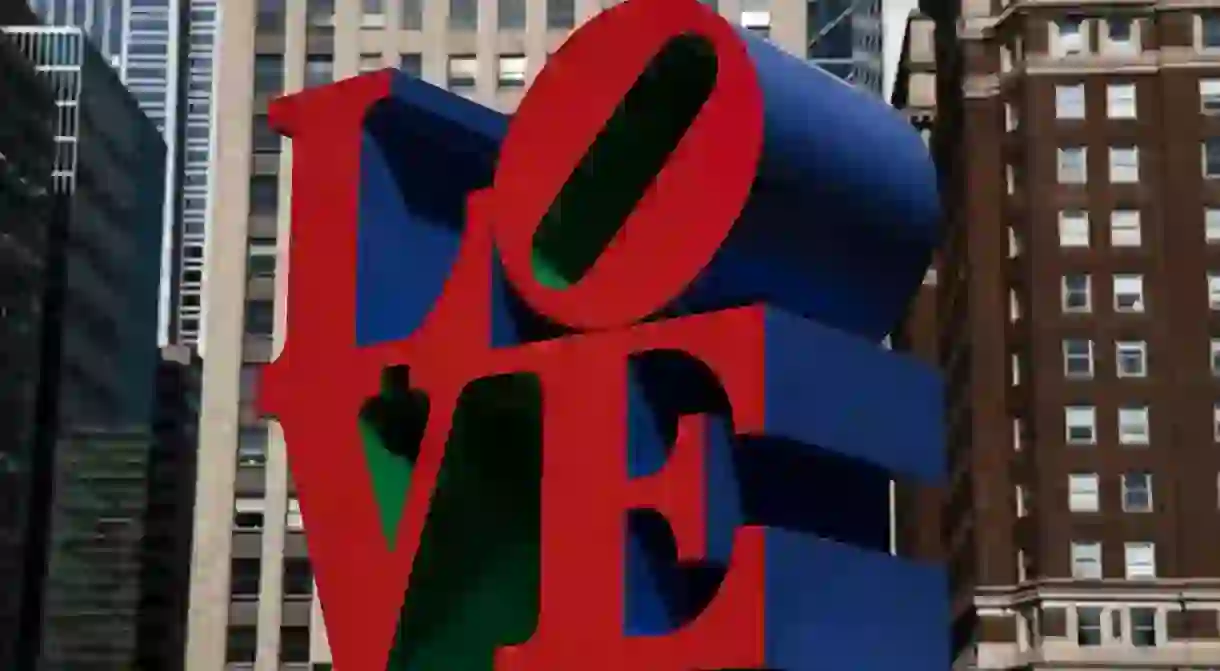

In the late 1950s, Indiana’s aesthetic morphed into an amalgamation of these reigning contemporary styles, and he contributed to the American Pop-art movement in the mid-1950s and 60s alongside Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. He was already a known entity in the New York art scene, but in 1965, the Museum of Modern Art released a printed Christmas card with the letters “LO” stacked above “VE” in red with a blue and green background, and this singular commission would evolve into Indiana’s most recognizable—and inescapable—series.

“The word LOVE got to be the way it is because I have a kind of a passion about symmetry and the dividing of things into equal parts,” Indiana once said. “The word LOVE is that way because those four letters best fit a square if the square is squared by that particular arrangement. And it was really that sort of a necessity for a very compact form that I came upon that arrangement…With the red, blue and green paintings the interaction in the eye is of such a nature that with the slightest change of light the fields automatically interchange, the positive becomes negative and vice versa, with almost a violent effect in the eye.”

LOVE became so popular that it eclipsed the entirety of Indiana’s oeuvre. The artist created several variations on this theme using the words EAT, HUG, DIE, even AHAVA and AMOR (the Hebrew and Spanish words for love), but the striking simplicity and affirming message of the original iteration, especially amid the Love Generation of the 1960s, rendered this particular motif the most enduring of his career—at the cost of everything else he ever created.

His eventual disillusion with the New York City art scene, which repeatedly criticized and dismissed Indiana as a one-trick pony, prompted the artist’s retreat to Vinalhaven Island off the coast of Maine in 1978. There, he became increasingly reclusive until his desire for solitude became almost as famous as his work.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BjETtPxB-47/?tagged=robertindiana

It wasn’t until 2013 that the Whitney Museum of Art in New York City staged a major retrospective of Indiana’s practice aptly titled Beyond LOVE that the artist came back into the spotlight.

“LOVE, and its subsequent proliferation on unauthorized products, eclipsed the public’s understanding of the emotional poignancy and symbolic complexity of his art,” the museum wrote. “This retrospective reveals an artist whose work, far from being unabashedly optimistic and affirmative, addresses the most fundamental issues facing humanity—love, death, sin, and forgiveness—giving new meaning to our understanding of the ambiguities of the American Dream and the plight of the individual in a pluralistic society.”

In 2016, the Bates College Museum of Art held another retrospective, Robert Indiana: Now and Then, which was the last Indiana would live to see. It exhibited some 70 works, with his most famous and lesser-known pieces sitting side by side.

Indiana continued to work from his home studio in Maine, revived by his retrospectives. In 2008 he created HOPE, a new artwork in the style of LOVE, for former president Barack Obama’s campaign. But in recent years, the artist, who didn’t have a family of his own, became worryingly distant from his friends and colleagues.

Just one day before Indiana died, the Morgan Art Foundation, a licencing company that had worked with the artist, filed a federal lawsuit in New York against art dealer Michael McKenzie, his editions company American Image Art and Indiana’s caretaker Jamie Thomas for copyright infringement and breach of contract, among other claims. The Foundation alleges that these defendants were creating unauthorized reproductions of Indiana’s artworks. The artist himself was also named as a defendant, as he “provided the alleged power of attorney enabling the creation and sale by other defendants of infringing works,” but the Foundation were unhappy in doing so, as they believed Indiana’s vulnerable state had been exploited by McKenzie and Thomas.

Speaking to artnet News Mckenzie responded: “Numerous counterclaims will be filed and we will have more to say shortly.”