Ways of Seeing: Three New Art Publications Reviewed

A look at a critics memoir, a series of artist profiles, and a classic example of ekphrastic writing

1977 is a year so infamous in New York City’s history — Son of Sam, the Manhattan Blackout, the birth of Hip Hop — that it has elicited think pieces, novels, and even its own documentary. If you pick away at its timeline of events, you’ll undoubtedly come to an exhibition curated by art critic and historian Douglas Crimp, simply titled Pictures. Organized by Artists Space, a young gallery that has since become a vaunted NYC institution, it had invited Crimp to be its first outside curator, and would create its first catalogue for an intimate show highlighting five artists — Sherrie Levine, Jack Goldstein, Philip Smith, Troy Brauntuch, and Robert Longo. These five artists would define the then, burgeoning (but still underground) genre now generally classified as postmodern image.

“It could have included many more artists,” writes Crimp in his newly published memoir Before Pictures, “but when I had to decide between a small, focused group show and a larger survey I chose the former.” The show’s opening was modestly reviewed by caught on by word of mouth, helping give its reception legendary stature. As Guggenheim curator Nancy Spector wrote in 2008, “Today, Pictures has entered the pantheon of paradigm-shifting exhibitions, comparable to first exhibition of Futurism … the introduction of Suprematism and Constructivism … and the consecration of conceptualism.” Crimp, unsurprisingly, has complicated feelings about the show’s fame: “I respond to Pictures with ambivalence,” he writes. “It historicizes me.”

In Before Pictures, the now lauded critic examines his formative years. Crimp was born in Coeur d’Alene, an Idaho city, he writes, noted as much for its natural beauty as it is for its xenophobia (it was the birthplace of the Aryan Nation neo-Nazi movement). Crimp doesn’t explicitly hate on his home town (he boasts that his sister was, for many years, Coeur d’Alene’s three-term progressive mayor). Still, as a gay man in a conservative American town, Crimp made sure to leave as soon as he could, first to college in New Orleans where his sexuality blossomed, and then to New York where it doesn’t, at least at first: “I would have to learn how and where to be queer all over again, since being queer is a matter a world you inhabit, not something you simply are.”

Nor is this book simply a memoir. Crimp doesn’t write a straight narrative account of his life. Often he gives in to digressions, asides, and material that might better serve the text as footnotes. Where one scene may end with the “I” another may begin with the “eye” — Crimps’ gaze abruptly shifting from mirror to image. One chapter begins with an examination on the color palette of artist Daniel Buren, then abruptly shifts to Crimp talking about his first New York job: working at the Guggenheim. Right as one begins to wonder what all the fuss about Buren’s use of color was all about, Crimp picks the thread back up. Buren’s work, he tells us, had been was meant for a major Guggenheim show, only to be pulled at the last second at the request of Dan Flavin.

Crimp has the odd natural ability to be either at the right place or at the wrong place, but never it seems, at just a place. He’s fired from the Guggenheim, “presumably for knowing too much” about Buren’s removal, and his loft is burnt to a cinder from an explosion caused by a faulty heater. That same year he also lands his first curatorial show — an exhibition of Agnes Martin paintings (who is now the subject of a major retrospective at the Guggenheim). “It had the distinction,” he writes, “of being the first noncommercial exhibition of her work.” Crimp’s account of visiting Martin in far-flung Cuba, New Mexico (using a hand-drawn map provided by the artist herself), is one of the best anecdotes Crimp’s has up his sleeve. But then, again, Crimp takes a sharp right from memory lane stopping to examine Martin’s oeuvre at length.

He does the same too with artists Kelly Ellsworth and Cindy Sherman, dedicating not just passages, but pages, at times the majority of a chapter to their work. Especially with Sherman: “I will always regret that I didn’t appreciate Sherman’s early work fully enough to include her in Pictures.” There is a sense of the critic using this book to provide overdue attention. This can be discombobulating, but it also serves to underline a statement — Crimp wouldn’t be the critic he is today without having spent significant time with these artists. But nor is he an apologist or always so buttoned up. There are as many art parties in Before Pictures as there is art criticism, especially when Crimp transitions from curatorial to critical for places like Artnews and Artforum, before finally putting the art aside to enjoy the fruits of the city. In one chapter, Crimp takes to describing the debauchery he found at the house of John Ashbery, who for a time edited Artnews, and his exploits with the boyfriends of gallerists; in another Crimp is acquainting himself as much in Balanchine ballet as he is with disco balls. “I was trying to become serious as an art critic,” he admits, “right at the time I became a disco bunny.”

Crimp is as scrupulous a critic as he is a fantastic storyteller, and his personal portrait of 1970s New York is arguably among the most enthralling in print. On occasion, however, he dances around essential information without ever landing upon it, or perhaps presumes it to be pedantic toward his audience who might already know much of this material. For example, Crimp doesn’t quite clarify what brought about the genesis of Pictures, nor does he really describe the evening of its opening (though the book does include pictures of it). And October, the now defunct but glorious art magazine that Crimp edited, is only sprinkled about the book without it being given its full due. Before Pictures isn’t polished to give a clear portrait of Crimp’s come-uppance in the art world. But likely he prefers it that way. As Crimp puts it in his description of Gordon-Matta Clark’s City Slivers: “We glimpse the city in pieces, in the background, in our peripheral vision—and in recollection.”

***

In Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, one of the great satires on the contemporary art world, the eponymous protagonist is visiting the floating city during its biennale. Art from all over the world and in all its capacities is on display, either at the Arsenale or Giardini or within the UN of pavilions scattered across the lagoon. This creates an atmosphere where nothing is beyond critical assessment. Upon discovering a trash heap, Jeff is sent into an reverie, giving the piles of garbage a proper appraisal: “[It] had been compacted down into a dark tar, a sediment of concentrated filth, pure filth, filth with no impurities, devoid of everything that was not filth. . . On top of this was an assortment of browning marigolds, bits of soggy cardboard… and freshish-looking excrement. The whole thing was set off with a resilient garnish of blue plastic bags. In its way it was… a contemporary manifestation of the classical ideal of squalor. I was quite excited by it, was tempted to ask the driver to stop so that I could have a better look, perhaps even take a picture.”

This lampooning of art criticism might elicit both laughter and a bead of sweat from those actual critics who work to define the ephemerality of art. As writers Katya Tylevich and Ben Eastham point out in their new book My Life As a Work of Art, this is a necessary, albeit difficult, task; one that can either illuminate the contemporary or turn it even more enigmatic.

In a breath of fresh air, Tylevich and Eastham have assembled profiles of eight contemporary artists, stressing their impact by looking at a single work from each. Rather than written in the scholarly tone common to art criticism, Tylevich and Eastham write as immersive journalists, freely using the “I” to inject a sense of intimacy with their subjects. Here’s Tylevich in conversation with Marina Abramovic:

“Abramovic laments the fact that ‘we don’t dream anymore’. Dreams are a subconscious language, and there are a lot of things dreams can tell you. But we all use sleeping pills, or watch television, or get drunk, so we don’t dream.”

Tylevich asks if she’s ever used sleeping pills. “Not in my life,” replies Abramovic. “I sleep like a baby.”

The two are in conversation about Dream House, a site-specific piece that opened in the small Japanese village of Uwaya in 2011. In each of the house’s six rooms lies a casket bathing in the light of an LED. A different color for each room. Guests are asked to sleep in the room and record their dreams in a provided journal upon waking. Tylevich weaves in her own narrative of making the pilgrimage to Dream House along with a series of interviews, at one point catching the artist as she is doing her laundry. This hair-down approach allows Abramovic to talk about her work, particularly Dream House, in a way that you wouldn’t read on a wall text or filmed interview: “You’re there for a purpose and nothing else. You can’t sleep together in Dream House. You can’t have sex. The purpose is to concentrate on your bloody dream and dream.”

Eastham has equal success in catching the little bits of an artist’s mind. Describing French artist Camille Henrot (whom I’ve interviewed elsewhere), how her lucid, erudite, and tangential way of speaking—“as one thought emerges, she seems to recognise in it a possible connection to another idea, as yet unconsidered”—can be traced to her insatiable curiosity. On another occasion Eastham observes how, as Henrot worked on an installation at Chisenhale gallery, she would spend hours in a thrift store pouring over “its kitsch, abandoned tat.” The director Polly Staple tells him “More stuff just kept appearing in the hallway…[Henrot] had a very clear system, but conversations about the placement of, say, the CD cover, should it be next to a watermelon? Or next to a statue?…You have to say, ‘We’ll come back to that later…’”

This may sound like manic behavior, but Eastham uses this color of Henrot’s personality to illuminate the work that put her on the map: the cosmological art film Grosse Fatigue, a history of the cosmos at the “break-neck speed” of 13-minutes, propulsively narrated by the NYC artist and musician Akwetey Orraca-Tette, that uses hundreds of objects and material housed at the Smithsonian where Henrot was an artist-in-residence. “It functions as a work of internet-era mythopoeia”, writes Eastham on his experience of first viewing it, “an eclectic, mind-boggling agglomeration of physical artifacts, musical styles, cosmological narratives and belief system. As I walk into the screening room and back into the light, the world around me seems pitifully slow.”

It’s this narrative and prosaic quality that makes My Life As a Work of Art insatiably readable. By putting the reader into proximity with their subjects, Tylevich and Eastham make them human,understandable. Whether it’s Tylevich browsing the Home Depot website with artist Erwin Wurm for a bucket to fit a human head, or Eastham, who, in the midst of composing a chapter on Michael Borremans’ dark-humored Abu Ghraib painting BLACK MOLD, is called by the artist and informed the painting is no more. His plan for it had “changed”: “I’m sorry if this makes it difficult for your project.”

In the introduction provided by Marc Valli, editor-in-chief to the excellent contemporary art magazine Elephant, he states “contemporary art is not always easy; it is not for the fatuous and the intellectually incurious.” If anything, this book isn’t a primer for contemporary art, but a literary guide to its practitioners. “Money is not everything,” continues Valli, aware of the tight relationship between art and market. “The work of art is everything.”

***

If contemporary art is becoming the wheelhouse of the “sumptuously imaginative,” literature is right there along with it. In fact it always has been: ‘ekphrasis’ is a term used to describe the translation of a work into literature. It is also the name of a opulent new series of books being published by David Zwirner Books, the publishing arm of the renowned gallery. Among its first offerings is “Chardin and Rembrandt,” an essay written by Marcel Proust when the writer was in his early twenties. Proust proves to be a perfect exemplar of ekphrastic writing with his description of Chardin’s painting The Diligent Mother:

“There is amity between the sewing box and the old hound who comes in each day to his usual spot, lying as he always does with his soft, lazy back against its cushioned fabric. It is amity that so naturally draws to the old spinning wheel, where they will feel so at ease, the dainty feet of the distracted woman whose body unwittingly complies with habits and affinities she unknowingly accepts. Amity, again, or marriage between the colors of the fire screen and those of the sewing box and the skein of wool.”

All of this serves to lift the painting into another dimension of viewership, letting it move in time rather than be captured by it. The rich language complements Chardin’s oiled characters, and it’s that harmony that makes ekphrastic writing work. Part of Proust’s allure must be credited to translator Jennie Feldman who describes how she “sought to keep Proust’s exuberant tone and resonant cadences.” She notes how this essay prefigures Proust’s magnum opus The Remembrance of Things Past in its ability to connect “the things around us and our experiences of them.” So too does it figure in Proust’s more famous ekphrastic work, found in his grand novel’s final volume, in which the writer Bergotte encounters Johannes Vermeer’s View of Delft at an art exhibition.

“He noticed for the first time some small figures in blue, that the sand was pink, and, finally, the precious substance of the tiny patch of yellow wall. His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious patch of wall. “That’s how I ought to have written,” he said. “My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall.”

In his afterword, the aptly-named French art historian Alain Madeleine-Perdrillat writes that part of Proust’s genius lies in his instinct about what kind of writing a work of art demanded, in Chardin’s case, elegiac prose, where a poem or critical description may have suited others. But Madeleine-Perdrillat is careful to call Proust’s writings “critiques of quite an ordinary aestheticism to a supremely nuanced exploration of a wholly personal experience.” Meaning ekphrasis can, like any feat of the imagination, be boundless in its possibilities. For instance, Proust begins his essay not with the work, or even himself, but by imagining the viewer as character:

“Take a young man of modest means and artistic inclinations, sitting in his dining room at that banal, dismal moment when the midday meal has just finished and the table is only partly cleared. His imagination full of the glory of museums, cathedrals, sea, and mountains, he feels unease and ennui, a sensation close to disgust and akin to spleen, at the sight of a knife trailing on the half-hitched tablecloth that hangs to the floor, and next to it the remnant of a tasteless, undercooked cutlet.”

It’s an atypical way to begin an essay, but in Feldman’s translation, she allows Proust’s prestidigitations to soar. It’s through the eyes of a fictional young man, that Proust is able to assert what it is that moves him about these very real Chardin and Rembrandt paintings. He describes Rembrandt’s rendering of daylight, its alterations of the existence of objects in a sense of time that “seems to pass through all the agonies of death.” He remarks: “at such an hour we are all like Rembrandt’s philosopher.” Could it also be that the philosophy is as much in the gaze as it is in the description?

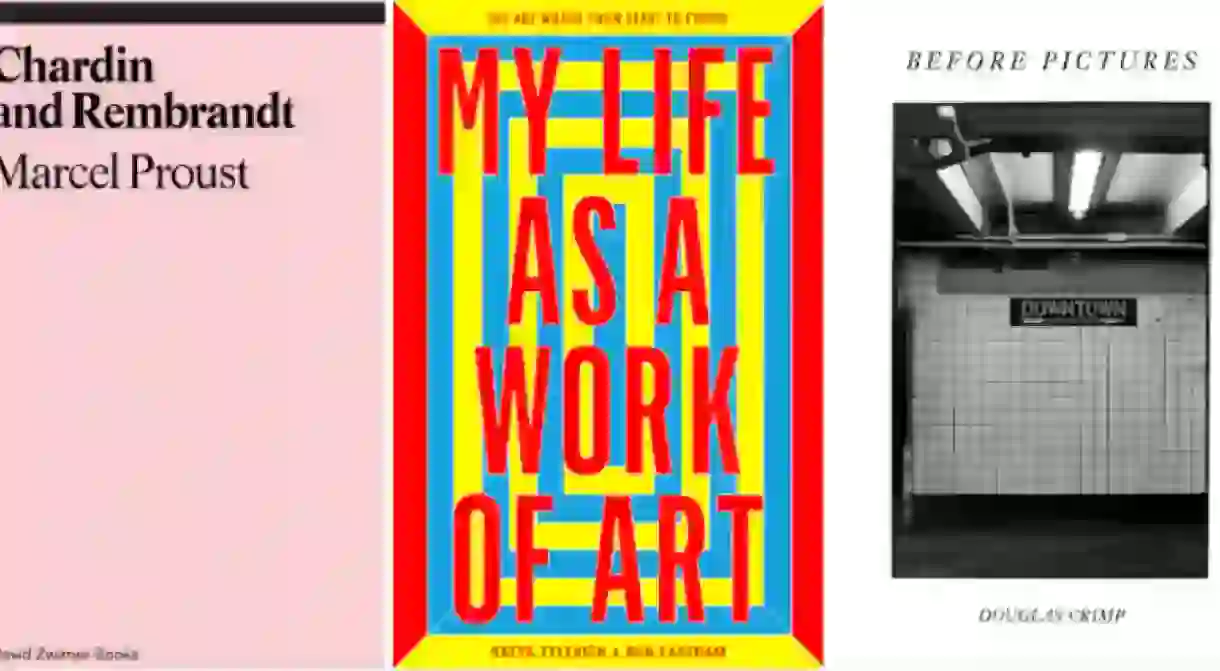

BEFORE PICTURES

by Douglas Crimp

Dancing Foxes / University of Chicago

288 pp.| $39.00

MY LIFE AS A WORK OF ART

by Katya Tylevich & Ben Eastham

Laurence King Publishing

336 pp.| $28.00

CHARDIN & REMBRANDT

by Marcel Proust, translated by Jennie Feldman

David Zwirner Books

64 pp.| $12.95