Celebrating Mexico’s Day of the Dead in San Andrés Mixquic

As visitors travel southeast out of Mexico City, they can expect to smell pungent incense and see venders at roadside market selling buckets of marigolds. Despite its evolution over the course of history, Mexico’s famed Day of the Dead has stood the test of time and offers a unique cultural insight into what the country’s people hold dear. Here Culture Trip examines how Día de los Muertos is celebrated in San Andrés Mixquic.

Though it might fall on Halloween, Mexico’s Day of the Dead is a far cry from the commerciality of the macabre holiday celebrated in other parts of the world.

With time-honored customs dating back to the indigenous Aztecs in 1100 AD, many consider Día de los Muertos as the oldest festival in the world. Originally observed at the beginning of the summer, it was moved at the time of Spanish colonization to coincide with All Souls’ Day (November 2nd) a tradition observed by western Christianity. Consequently, its practices are cherished in every country pervaded by Hispanic lineage and culture. But nowhere does it like Mexico, and as such UNESCO recognized the holiday as an indelible part of Mexico’s cultural heritage in 2003.

Día de los Muertos is not only a time for families to gather to commemorate the lives of their dead, but also to welcome their spirits back to earth. To this end, people create altars in honor of the dearly departed decorated ornately with fresh flowers. Prince among them is the marigold known as the flor de muerto (‘flower of death’) because many believe it attracts the souls of those gone before.

Altars are festooned with ofrendas, gifts chosen with meticulous attention to the tastes of the departed. Locals invest as much as possible to tempt the spirits to earth because the dead are believed to be the gatekeepers of prosperity for their surviving family members. Pan de muerte, (‘bread of the dead’) is scented with aniseed, and topped with sugar, candied pumpkin, artisan chocolate, fruit and even Mezcal, Mexico’s native drink.

Calaveras, or skulls, were believed by the Aztecs to represent the life cycle, and are still part of the celebration, from candied skulls, decorated with brightly colored sugar crystals to vibrant ceramic skulls lined up in rows at the local mercado. Likewise, homage is paid by people of all ages who paint their faces in variations on the skeletal theme.

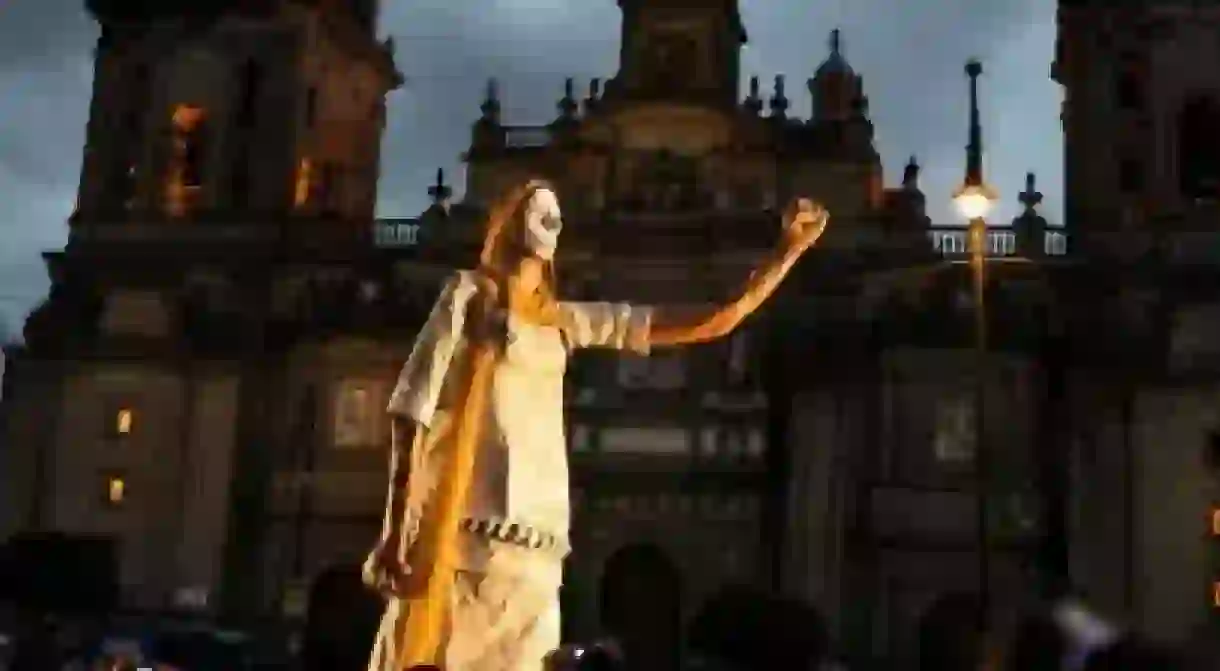

Santa Muerte (Our lady of the holy death) is the Mexican folk saint that officially personifies the celebration, worshipped not during her time on earth but for giving mortals safe passage to the miraculous afterlife in death. However, it is Calavera Catrina that has become the latter day poster girl for Día de los Muertos. Born of a satirical illustration created before the revolution to mock Mexicans aspiring to emulate the European elite, her poignancy became even more compelling in times of political and social independence.

On the day, mourners make their respectful procession to the graveyard surrounding the San Andres Apostol, a former monastery, where their family-owned plots are loaded with relatives spanning generations. Above ground it’s a similar story, with visitors from elderly relations rolled in wheel chairs to toddlers wrapped in swaddling cloth. Tombs are decorated in the same way as the altars, scattered with marigolds, ofrendas and candied sweets.

After nightfall, families gather graveside and pay tribute to the spirits of the deceased with an all-night vigil. Shadows dance on the granite crosses cast by twinkling candlelight. Incense burns a thick dense fog as cleansing rituals are performed to remove spiritual impurities. Patriarchs read a slow, morose roll call of the departed from the head of the grave. Glass-eyed mortals lost in a reverie of remembrance pray silently. It is incredibly moving to glimpse this very public grief, especially since this emotion is oft kept for privacy.

There has been Catholic resistance to the Día de los Muertos, particularly since the faith doesn’t acknowledge Santa Muerte. Many see the festival as the dilution of deep-rooted Catholic traditions with pagan practices. There is evidence of this in the commercial thrum of the mercado outside San Andres Apostol where the constant sizzle of grilling corn tortillas and perpetual chink of passing pesos drowns out the few cries of damnation. It’s not uncommon to see placards that read ‘Jesus has sent me to warn you.’

The emblems associated with the Aztec festival have certainly infiltrated Halloween celebrations across the world.

But, fancy dress aside, Día de los Muertos is a poignant, respectful and moving festival. There is something very uniting, supportive and dignified about celebrating the dead in one day rather than visiting a graveyard to grieve alone. It is the cultural embodiment of wearing your heart on your sleeve, and Mexicans do so with great aplomb.