A Brief History of Mexico’s Day of the Dead

The Day of the Dead is one of Mexico’s most widespread traditions, which is now heavily associated with Catrina skulls, all-night vigils, and Halloween. Although the Día de Muertos celebrations do roughly coincide with the more commercialised (and previously Pagan) Halloween festivities, there are in fact vast differences between the two events, despite their shared ‘Christianization’. Here’s our brief history of Mexico’s Day of the Dead.

The Day of the Dead is an annual tradition, now celebrated on November 1 and 2 (although preparations can take weeks), in which the living honour the dead, both so as to help them into the afterlife and encourage them to visit the world of the living for one night. November 1—often called Día de los Inocentes or Angelitos—is reserved for honouring deceased children, while the second day is for deceased adults. While the idea of celebrating death might seem a tad morbid in many societies, in Mexico it’s quite the opposite; death is not the end, it’s just a new beginning.

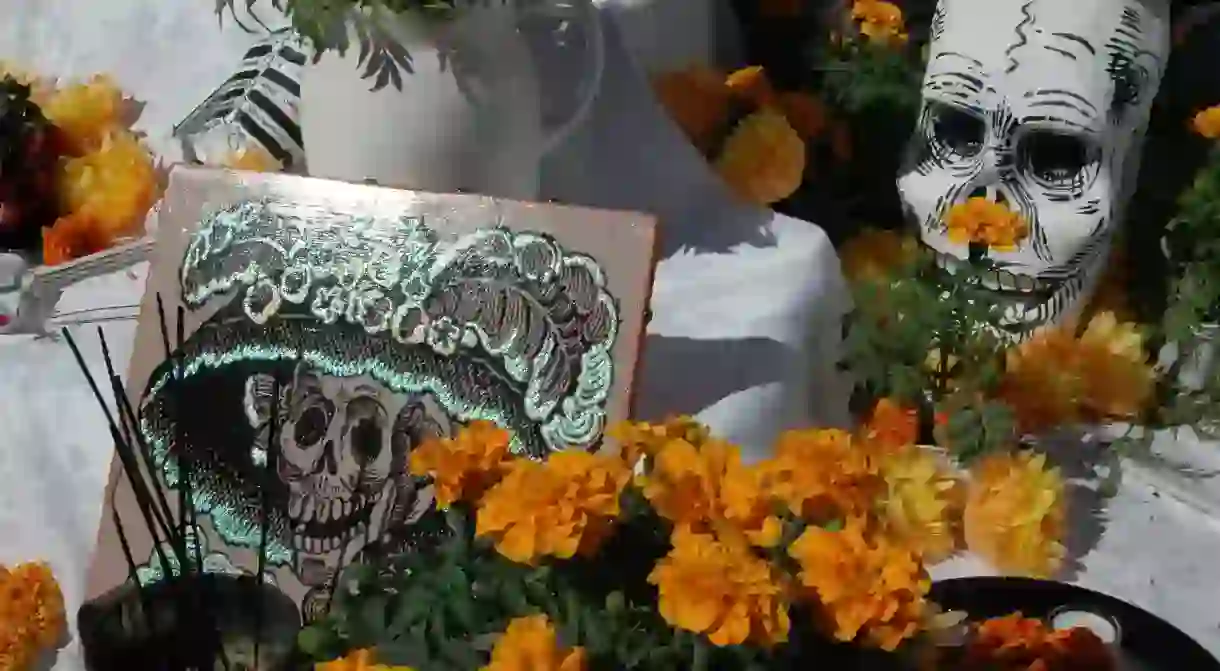

Día de Muertos is popularly celebrated by holding graveside vigils, at which altars honoring the deceased’s life are typically constructed. However, many people also choose to construct more private altars in their homes. These altars (altares) are decorated with the ubiquitous cempasúchil (Mexican marigold) flowers and candles, as well as skull iconography in some shape or form, and ofrendas (offerings) such as the deceased’s personal possessions, favourite drinks or foods—don’t be surprised to see cigarettes, cans of Coke and football shirts on a Day of the Dead altar! These items supposedly convince the deceased to return to the world of the living. Some other common traditions include the eating of pan de muertos, a distinctively shaped sweet bread which is lightly orange flavoured and covered in sugar, the creation of sugar skulls, and painting one’s face to look like that of a Calavera Catrina. (The latter is admittedly much more of a traveler tradition than a local one.)

The origins of the Día de Muertos are rooted in Mesoamerican culture and possibly Aztec festivals that celebrated the goddess Mictecacihuatl. However, the festivities are now more widespread than they were then. Predominantly native to southern parts of what is now Mexico, the north of the country, due to different indigenous groups and rituals, was in fact only introduced to this tradition within the last two centuries. Either way, due to the arrival and influence of Christianity which sought to annihilate many indigenous rituals, the festivities we see today in all likelihood vary somewhat from the Mesoamerican Día de Muertos celebrations. This is most true when we consider the moving of the festival’s dates; previously celebrated sometime around early August onwards, Christian influence shifted the Día de Muertos to All Hallows’ Eve and All Saint’s Day. Ultimately, the Day of the Dead is now an agglomeration of various different cultures and beliefs.

Even so, the Day of the Dead holds such cultural significance that in 2008 it was declared a UNESCO event of ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’, and in the 60s it was introduced to Mexican school curriculums, which led to its designation as a national holiday. If you want to respectfully immerse yourself in the festivities, some of the most typical places to visit during the Day of the Dead period are Michoacán’s Isla de Janitzio or Oaxaca City, where parades, vigils and concerts are held to celebrate the occasion. Outside of Mexico, Europe and the US observe many Mexican Day of the Dead traditions, such as honoring their dead by making offerings and visiting gravesides on All Saint’s Day. Brazil too celebrates Finados (Day of the Dead) on November 2, whereas in Bolivia, a similar day (Día de las Ñatitas) is celebrated on November 9.