This Star-Shaped Cell May Change the Future of Architecture

Astrocyte, a design spectacle in Canada, gains international attention as a prototype for future interactive architecture.

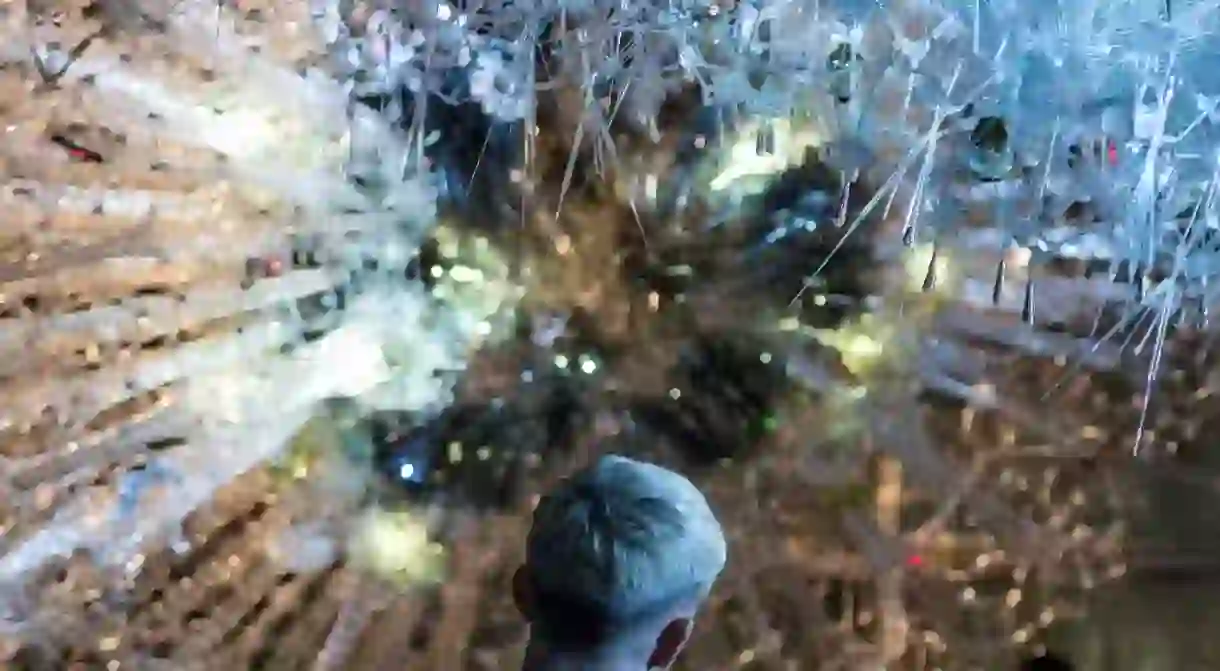

Using 300,000 custom components, Living Architecture Systems (LAS) created an interactive sound installation for Toronto’s 10-day festival, EDIT (Expo for Design, Innovation & Technology) back in October—and since then it has gained world-wide attention.

LAS designers consider the immersive installation as a new testbed for the future of architecture, one that incorporates chemistry, artificial intelligence, and kinetic systems of electronics. At the core of the 3D structure, a star-shaped cell made of electronic actuators and sensors responds to viewers’ motions. The installation behaves as “a harmonious swarm of insects,” says LAS’s director, Philip Beesley.

Sure, the structure is a stunning visual explosion, but what’s the experience of it like? Patterns of light envelop the viewer, while a complex, spatialized sound system (created by Netherlands-based sound artists 4DSound) creates a multidimensional experience through acoustics. The goal, according to LAS, is to create environments that can feel and think with us, even empathically.

Made from a thermally-formed acrylic meshwork cut into geometrical patterns, the structural forms are clustered into bundles. These bundles are, in a sense, anthropomorphic—they closely resemble the “multiple filaments spanning between outer and inner shells of natural bone structures.” The result is a resilient design that is able to support a variety of motions and forces.

So how does “chemistry” come into play here? LAS uses “artificial chemistry” suspended as custom glass, which combines “oil, inorganic chemicals, and aqueous solutions” to create chemical skins. These skins, according to LAS, may perhaps form basis for a future prototype of self-renewing skin for future architecture.

Astrocyte is, according to the designers, part of a larger framework for interdisciplinary research, one that centers around art, architecture, science, and engineering. It serves as a catalyst for new dialogue, hoping to address questions surrounding the future of built environments.

What does the future of architecture look like? How can robotics help build symbiotic exchanges between humans and the built environment? How can we better adapt to the ever-evolving social and environmental landscape? And, even more daring perhaps, can future buildings or structures become conscious? Will they one day be able to think, or care?