Defining the New South: Faulkner, Williams and Wright

Flannery O’Connor, the doyenne of Southern Literature, famously said that literary portrayals of the South must ‘distort without destroying’; Lindsay Parnell looks at how this dictate was followed by three iconic Southern writers: William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams and Richard Wright.

The South is plagued by a historical hangover of failure and ‘well-publicized sins’, said O’Connor in a lecture to students on ‘the Regional Writer’. The literature of the South must therefore interrogate these historical sins, as well as confronting their legacy; the bigotry that for some has come to define the region. Writers and artists must play a pivotal role in the attempt to re-craft a progressive ‘New South’ or risk being subsumed by the regressive cultural norms of their day.

Southern writers have thus articulated the often silenced voices of marginalized identities in the American South. This concept has been explored in the revolutionary work of writers William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams and Richard Wright, whose work examines a resurrected but broken South.

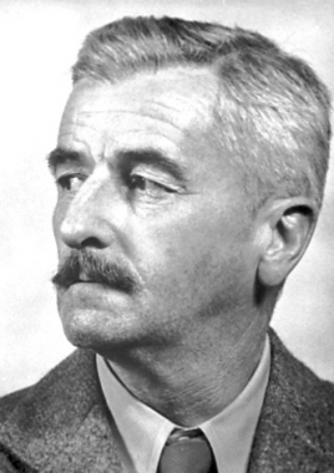

Born in New Albany, Mississippi in 1897, William Faulkner has maintained his reigning deity status of Southern Literature since the publication of his first novel, Soldier’s Pay (1926). The fictional county of Yoknapatawpha, Mississippi is home to many of Faulkner’s novels (14 of his 19 are set there). His most productive period, from 1929 until 1942, featured the publication of novels including The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Sanctuary (1931), Light in August (1932), Absalom, Absalom! (1936) and Go Down, Moses (1942), all of which have been acclaimed as classics of both of Southern writing, and canonical works of English Fiction.

Throughout all of his fiction, Faulkner explored the idea of the American South as breeding a sense of the abject within impoverished communities. In his work this region is plagued by ‘others’, deviants that threaten the structure of society and law, who have subverted the codes of normal society. He did this through a narrative lens of historical and regional tension, incorporating war, poverty and racial injustice into the seams of his fiction. Faulkner’s astounding articulation of the South’s cultural pathology sees the region as one which is haunted by the crimes of its past, and characters as having internalised the pathology of guilt, until history itself becomes a wilful and pernicious presence. It was a body of respected work that earned Faulkner a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949.

A brilliantly dominating presence of American theatre, Tennessee Williams explored the ‘New South’ for the stage in his forty-year literary career. Born Thomas Lanier in Columbus, Mississippi, Williams’ relocation at a young age from St. Louis proved damaging as it distanced him from his home. This move however would assist him in discovering the founding principals of what would become his dramatic canons—characters victim to psychologically debilitating isolation and detachment from any society or community to which they could belong.

Williams’ prominent dramatic scripts highlight the underlying humanity of the South, often buried under discrimination and intolerance. His examination of the conflict existing between the public and the private defines his numerous works of drama and prose alike. His stage plays famously explore deeply dysfunctional families in a post-Civil War South. Along with inquisitions into the role of religion and sexuality, Williams’ characters seek out the boundaries of their own self-hood while simultaneously seeking out a regional identity.

The playwright’s preoccupation with the emergence of a ‘New South’ is depicted most famously in A Streetcar Named Desire (1947). This Pulitzer Prize winning drama tells the story of the ‘expired’ Southern Belle, Blanche DuBois, who has moved in with her sister Stella and violent brother-in-law Stanley in New Orleans. Nearly a decade later, Williams published Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955, Pulitzer Prize for Drama) in which a birthday celebration for Big Daddy’s birthday on the family plantation in Mississippi turns sour when his two sons wives return home. The domestic turmoil is tangible in a tangled matrix of anger, resentment and the lies of family secrecy.

With an acclaimed canon of novels, poetry, memoir, screenplays stage plays, Tennessee Williams still remains an incontestable dramatic force investigating still relevant questions for the South. Williams’ courageous exploration of sexuality is comparable to the stirringly inspiration investigation of racial prejudice in the work of fellow Mississippian, Richard Wright.

Born at the turn of the 20th century, novelist and short story writer Richard Wright experienced an impoverished childhood in Mississippi. His family moved from Mississippi to Memphis, Tennessee only to witness the tragic death of Wright’s father. Shortly after the death of his father, Wright’s mother moved her children to Chicago. After school Wright became a member of the Communist party before relocating to the famous cultural hub of Harlem in 1937. This move would prove to be one of the most influential and creatively inspiring events of Wright’s life as he was consumed by the artistic spirit of the Harlem Renaissance. Wright also spent time abroad in Paris befriending fellow literary expat and novelist James Baldwin.

Questioning the state of race relations in the United States was the nucleus of Wright’s literary preoccupations. Wright’s most distinguished and critically acclaimed work, Native Son, was published in 1940. Native Son is the story of the greatly impoverished Bigger Thomas, a young man living in Chicago. Bigger feels the pressure to provide financially for his family. He becomes involved in a life of petty theft to protect and provide for his family and is a victim of racial prejudice. The racial injustice plaguing his life forces him to commit unspeakable acts in the name of survival. Wright never excuses Bigger’s behavior throughout the novel, but presents a captivating character study of someone who is a victim of his own social conditions.

Faulkner, Williams and Wright all present enthralling and challenging multifaceted portrayals of the Southern identity. An understanding of the American South calls for an explicit recognition of a culture defined by its violent oppositions and a reality removed from its antebellum notions of plantation wealth and Southern grandeur. This is evident in the work of these three great writers, who, by interrogating the prejudices of their native land, redefined what Southern culture would come to mean.