The Stunning Mayan Murals of San Juan La Laguna, Guatemala

Young Mayan artists from Lake Atitlán are preserving their culture with dazzling murals.

The word for ‘artist’ is the same as the word for ‘healer’ in Tz’utujil, the Mayan language spoken in San Juan La Laguna on the shores of Guatemala’s breathtaking Lake Atitlán.

The town’s young artists paint murals to promote Tz’utujil identity and philosophy. Artist Diego Ixtamer explains, “We’re losing a lot of our culture, and we’re living in a way that damages our culture and damages our Mother Earth. That’s why with our art, we try to cure people, to cure the community.”

The young people of the Jovenarte collective created the town’s longest mural. It’s in the town center, where speeches are made, kids play basketball and soccer and bands play in the evenings.

The mural begins with a spiritual guide who blows into a censer. Mayan ceremonies use smoke to communicate with the divine. Pablo Toj, a member of Jovenarte, explains that the elder is “petitioning for what he seeks. Through the fire, the smoke, you can create. The rest of the mural flows from this.”

The vase in his head represents the town, which in Tz’utujil is called Xe Kuku Aab’aj, ‘below the vase-shaped rock.’ The colored crest is a pattern from the town’s traditional cotton blouses called huipiles. The symbol in the center is one of 20 nahuales, representations of divine energies in Mayan spirituality. It is Ix, a force that commonly embodies the power of nature and ceremony.

A corn stalk rises from the censer and its flower is tipped with jade, representing the Tz’utujil people and language; tz’utujil itself means ‘cornflower.’ Meanwhile, a weaving emanates from the censer, holding wooden pieces of the backstrap looms that women here have used for centuries to weave meaning into clothing with specific colors and patterns.

The weaving continues throughout the mural, because, Ixtamer says, “We’re all threads in the weaving of the community, and through our actions, we weave our community and its future.”

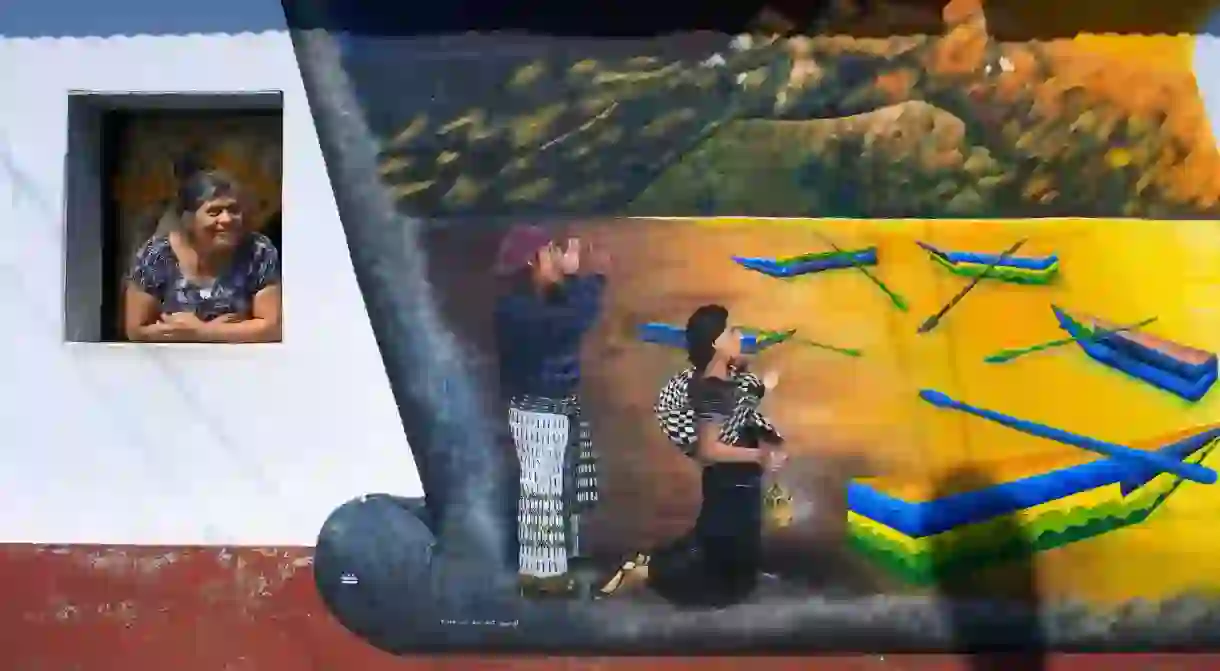

The next image, with the weaving in the background, depicts the woman from San Juan who won the national Rabín Ajaw competition, which every year selects a woman to represent Guatemala’s indigenous peoples. The competition focuses on the contestants’ public speaking, in Spanish and indigenous languages, on social programs they would support as Rabín Ajaw. The woman wears the town’s traditional dress and on her crown rests a quetzal, Guatemala’s national bird and a symbol to Mayan communities of their culture and of five centuries of resistance to colonization.

Next, an elder and a boy appear. They face away from each other, the elder looking back toward the mural’s origin and the boy looking forward. The elder holds thread and the boy holds a woven textile. “The future of our traditions is uncertain,” explains Toj.

Ixtamer painted a piece called Kamiik. He explains that in Tz’utujil, “Kamiik means both ‘today’ and ‘death.’ There’s a connection between them, and to the cyclical nature of time. I’m here today, but if I die, someone else is approaching. It’s necessary to leave this space for another to be born. The skull and the flower, it’s life and death. It’s this moment.” Ixtamer adds that the rabbit represents the nahual known as Q’anil, the seed from which life grows and evolves. He says, “The rabbit has a deep connection to women who give life and give birth.”

Next to her is a young boy, the first character in Western clothing, holding a bass. The Guatemalan government introduced bass into Lake Atitlán in the 1970s to offer tourists a familiar meal, and they devoured many of the fish that the locals depended on. Ixtamer says, “This mural speaks a lot about the damage we’re doing to nature, and how in the end it’s the children who suffer.”

Across the street, Pablo Toj painted What Flowers From My Gray Hair with three other Jovenarte members. The woman pictured over a bed of flowers is a Mayan midwife who uses both traditional and modern treatments to care for pregnant women before and during birth. Toj says they painted her to represent the legacies of today’s elders, and to reflect on what legacy today’s youth might leave when they are the elders. Toj says, “Everything we do eventually must flower in a younger person. Everything I do leaves its mark in someone else.”

He also says the other woman and the red flower above her represent hope. “Many women here call themselves kotzij [flower]. The flower of life, the flower of humanity. The flower we all need.”

Ixtamer painted this mural in 2012 to commemorate the Oxlajuj B’aktun, the end of a 5,126-year Mayan calendar cycle. Ixtamer says, “Lots of foreigners were saying it was the end of the world, but no. Our elders knew that this was the end of one cycle and the beginning of another – a new cycle of consciousness.”

Where sand meets water and waves come and go sits a spiral conch shell. Mayan elders blow conches to begin meetings and ceremonies because they symbolize cycles and new beginnings. In the conch is Mother Earth.

Ixtamer says, “The bubbles reflect pollution, how we’re harming Mother Nature. We want to start a new cycle, of sand, of hope, of shells full of flowers and butterflies. It’s a commitment we need to make to nature. It’s time to make ourselves conscious, and make real change, like a butterfly does in a cocoon.”

This mural depicts Jorge Itzep, a member of the Tz’utuj Q’ajom Mayan music and dance collective. The muralists painted it to honor the young people who practice traditional arts. Each instrument is accompanied by the animal whose voice it mimics, but each animal also represents a nahual: the dove is Tz’ikin, the hummingbird is Iq, the woodpecker is Noj and the jaguar is Ix. Ix was included to honor the women of the town.

Ixtamer and Toj say this mural, painted by Lix Mendoza, is their favorite. It depicts a traditional kitchen scene. The three hearth stones inscribed with nahuales play a central role in Mayan spirituality.

Ixtamer says, “Sometimes I’m asked where my studio is. I think our studio, the place where our art is born, is the kitchen. In those three stones, in the stories that our mothers told us about what’s happening, what’s happened, what they’ve lived. This is really our studio, because we learn our history there. Everything begins there.”

Ixtamer doesn’t know how old he is, and only went to school for three years. Like the other artists, he was not paid to paint the murals. But through them he finds himself. “School doesn’t teach you how to be an artist. Here, we believe that through life, you have to find yourself, through your community. Our elders use a word: noqmeloje, ‘to return.’ To untangle ourselves, decolonize ourselves. To find ourselves, to have a positive vision for the future, we have to rescue our philosophy, our culture. That’s why we paint these murals.”

For information, tours or to visit the Jovenarte museum, visit Jovenarte on Facebook.