Belfast’s Murals: The Politics and the Passion

The familiar adage ‘if these walls could talk’ is a statement animated and invigorated in the murals of Belfast: as an artistic mirror for political discontentment and cultural disjunction across the last century, they reflect the troubled history of Northern Ireland in a glaring, abiding and overwhelmingly moving fashion. We explore the role the murals played in The Troubles and how their meaning has changed in 21st century Belfast.

Contrary to popular opinion — held, perhaps, by those for whom the tumult of the 1960s through to 80s still resonates — the creation of political murals in Ireland can be traced back as far as 1908. These early examples, which often show images of William III, Protestant victor over the Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, began to appear from the brushes of Unionists protesting against home rule for Ireland. Since then a tradition has been cemented, with murals becoming not only a cathartic and reactionary outlet for frustration and change, but a much cherished part of Northern Irish culture, artworks ranging from Republican and Loyalist statements of anger, resentment or hope, to colourful celebrations of George Best and detailed representations of characters from C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

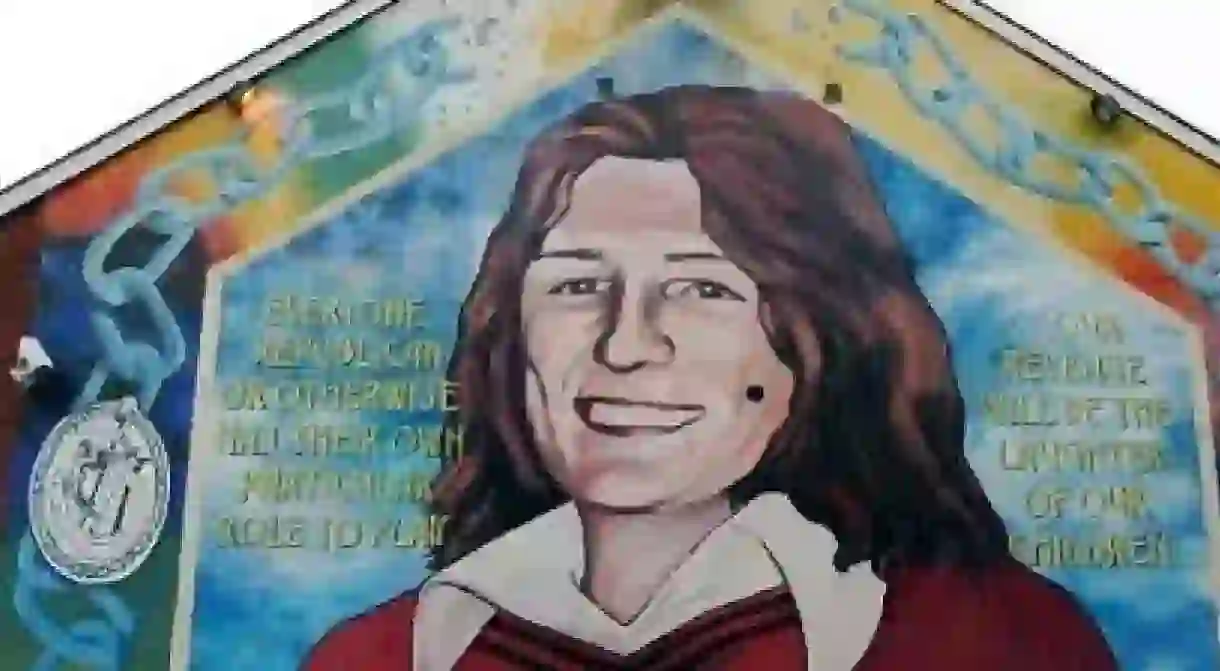

To begin any narrative tour of the Belfast murals however, one undeniably has to begin with the political and religious undercurrent pulsing through the majority of images. To inscribe and lacquer abrasive brick work with passion and fervent belief demonstrates the strength of conviction experienced by each individual Northern Irish wall-artist. The Republican murals that run through Falls Road, Donegall Road and the Ballymurphy district in West Belfast, New Lodge Road in North Belfast and Ormeau Road in South Belfast, began to appear in the 1970s and 80s as a result of Republican prisoners initiating a hunger strike to gain recognition as political prisoners, protesting against the removal of Special Category Status. All of a sudden, murals sprang up as a sign of recognition, gratitude and support, none more recognisable than the mural dedicated to Bobby Sands on the Sinn Fein offices in Sevastopol Road.

Bobby Sands, the famous volunteer for the Provisional IRA imprisoned in HM Maze, was the leader of the 1981 hunger strike – to which he eventually lost his life in the same year. Above Sands’ iconic smiling face is the phoenix rising from the ashes, signifying the rising of Ireland out of the flames of the 1916 Easter Rising. The Phoenix breaks the top of the chain surrounding Sands, just as the lark – representative of a pure voice and self-discovery – splits the links at the bottom of the mural, demonstrating his commitment to cutting through governmental restraint. Left and right sit the symbols of United Irishmen – the harp with the absence of a crown, but with a cap of liberty.

Compared to the symbolic richness of the Republican murals, the Loyalist equivalents are known for exuding a more defiant and militaristic tone, such as the relatively recently produced mural on Shankill Road (2007), depicting the illegal terrorist organisation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Central to the frame is the UVF insignia, guarded by paramilitary figures and crowned by the ethereal faces of five dead members: Robert Mcintyre, Robert Wadsworth, Thomas Chapman, James McGregor and William Hanna, who sacrificed their lives to the Loyalist cause.

Another pertinent Loyalist example is the mural on Hopewell Crescent, Lower Shankill, created in 2000. The mural intertwines three organisations, the Ulster Defence Union (UDU), established in 1893 to resist home rule legislation, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), established in 1972 for the defence of Protestant/Loyalist areas and the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), the alias for the military section of the UDA. The mural attempts to demonstrate what the artist perceives to be the correct, historical trajectory for Northern Ireland, displaying an armed contemporary UDA member against sepia-effect representations of nineteenth-century defenders of the crown in Ireland. In so doing, the mural cements a notion of natural progression, albeit in a clearly military vein, stamped with the flags of England, the UDA and Scotland, each individually crowned and sharing the familiar motto ‘Quis Separabit’ – ‘Who Shall Divide Us?’.

The pride instilled in the production of both these opposing political murals embodies the maxim repeated across Northern Ireland – ‘some gave all and all gave some’ – echoed both metaphysically in the minds of those affected and physically in the consistent reminder produced by the murals. Whether Loyalist or Republican, both sides of the Northern Irish social divide lost cherished members, whether in defence of the crown or in defence of an autonomous Ireland.

In recent years, given the gradual peace that has begun to infiltrate uneasy hearts and minds in the region, murals have taken on a more playful dimension. The loss of George Best in 2005 gave rise to the creation of his memorial mural (2006) on Blythe Street in Sandy Row, South Belfast. The badge for Manchester United sits comfortably alongside that of the Irish Football Association, with George Best in motion at the centre, commemorating his greatest moments at both clubs. The nationally and internationally acclaimed and much-loved East-Belfast-born author C.S. Lewis is also well represented in the city, with frequent murals adopting the theme of his enchanting work of fiction, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Perhaps the most spectacular example is the broad stretch of artistry on Pansy Street//Dee Street in West Belfast (2009). The bold lettering of ‘Narnia’ strikes up undeniable similarity and affiliation with the bold lettering of the political mural campaigns, yet heralds a new era of Northern Irish culture, embodied by the brilliance of imagination and fervour of creativity rather than the passion of political warfare. The roaring figure of Aslan moves into the famous street-lamp that served as the iconic meeting point of Mr Tumnus and Lucy, set against the cold hills of Narnia and overlooked by Lewis himself.

This brief journey through the story and checkered history of Belfast’s murals concludes with the ostensibly simple design on Balfour Avenue, off Ormeau Road. As part of a wider art installation in 2001, comprising the ‘Ten remaining unanswered questions in Science’, one particular gable-end, created by Liam Gillick, now reads ‘how can quantum gravity help explain the origin of the universe?’. As the Lonely Planet Guide to Belfast states, this particularly odd piece of mural art is perhaps the most poignant of the recently created examples, reflecting the still unanswered and as yet unsolved problems underlying Northern Ireland’s Sectarian divide. Unseen natural forces are as baffling as the minds of people and the wildfire contagion of ideas and beliefs, thus perhaps the silence created by an unanswerable question is the best neutral tribute to the creators of the murals and the people to whom they are dedicated.