Wimbledon's Global Appeal at Odds With Its Elitism

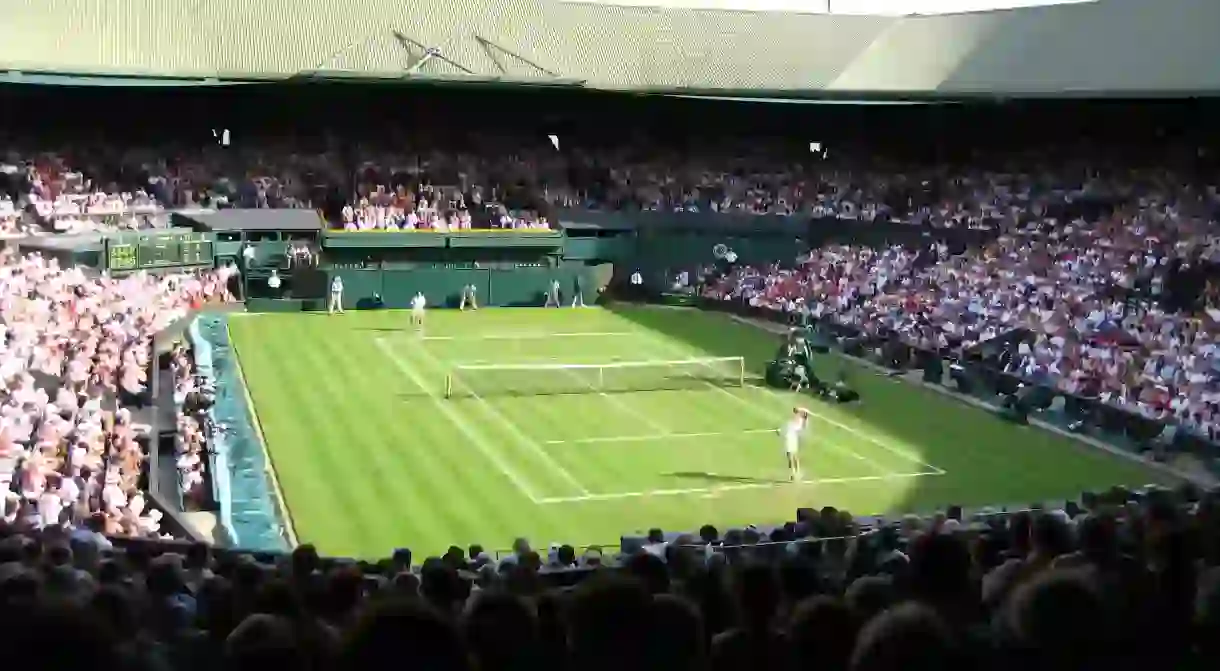

Held in a leafy corner of London every year, Wimbledon has gone from local fund raiser to one of sport’s biggest events. But while it presents itself as a tournament for the world to see, it has an exclusivity that is tailor-made for the few.

Philip Brook is the Chairman of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, where Wimbledon is held every year. Brook has been a member since 1989 and was elected to the Committee in 1997, becoming Chairman in 2010. In a talk hosted by Harvard Business School, at London Capital Club, he discussed Wimbledon’s continued success in staying at the forefront of the game and maintaining its status as ‘tennis’s premier tournament’.

Wimbledon’s numbers are undeniable. Revenue for 2016 topped £200m, with roughly three quarters of that coming through commercial avenues, mostly comprised of broadcast rights sold around the world to the likes of the BBC and ESPN. The ballot the Club does annually for ticket sales is oversubscribed by a factor of ten and when Andy Murray won his first Wimbledon title in 2013, beating Novak Djokovic, 17.3 million people watched on television in the United Kingdom, a quarter of the country’s population.

Brook is well aware there are caveats involved. Wimbledon’s ever increasing revenue is in line with the other three Grand Slams (Roland Garros, the Australian Open and the US Open), which, in turn, is in line with the sport’s continuing growth and popularity with audiences. An enormous contributing factor to this is what Brook describes as a ‘golden era of men’s tennis’. As a quartet, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Murray and Novak Djokovic have driven the game to unprecedented levels of performance. It is always difficult to judge what is happening around you, comparing it to bygone eras of yesteryear, but the men’s game has been nothing short of astonishing for over a decade.

Brook’s concerns didn’t include the women’s game. In fact, during the entire night’s proceedings the only mention of women’s tennis was of Joanna Konta’s 2017 semi-final match topping the TV ratings. There was no mention of what may happen once the Williams sisters retire. The Club’s attitude to women has been raised by observers. During last year’s tournament, Murray called for more women to be scheduled on Centre Court. Wimbledon does award equal prize money, and highlights this regularly, but the scheduling of female players suggests the Club values their expertise less. All this in a tournament where Venus Williams was reprimanded for the colour of her bra.

Amid Brook’s potential concerns or risks going forward, along with the likes of factors such as terrorism, reputation and scandals such as doping and match fixing, he highlights that a drop in performance from ‘the big four’ could have a genuine, detrimental affect on Wimbledon’s popularity. That said, as Brook points out, ‘these are concerns for tennis as a whole, not just Wimbledon. I do, however, believe that Wimbledon has built up a reputation and a status that ensures we would be most resistant to any drop off, compared to other tournaments around the world. People will still want a day out at Wimbledon’.

So how has a 140-year-old tournament managed to go from 22 men playing in front of 200 people for the grand prize of 12 guineas, to one of the biggest sporting events in the world? According to Brook, it is a matter of combining two seemingly opposing qualities – tradition and innovation. While new courts are being built, retractable roofs are being added to the show courts and media centres are being developed, there are strict rules about keeping the surface as grass, insisting players wear white and all the other traditions that have club members puffing their chests and tourists revelling in ‘isn’t it so quaint and British’ wonderment from the moment they buy their first tub of strawberries.

‘Long term planning is essential’, Brook explains. ‘In the early 1990s the Club put in place an 18-year plan of infrastructure that reviewed and assessed consistently over that time period. Pretty much everything within that plan was met. We also have something we call “The List”, which we check off every year that ensures our standards remain at the place we want them to be consistently. This list alters over time and its items can be very minor, or relatively large, but all of them have to be met.’

‘The List’ is a fascinating insight into how the Club works. In 2017 there were 1,500 items on it, ensuring excellence to the nth degree. The alignment of the site’s benches in relationship to each other, the height of the grass on the courts and even the shade of the petunias in the flower baskets are all on ‘The List’.

But while such levels of detail are impressive, it is difficult to see past the faults. Just as Brook champions tradition and innovation walking hand in hand, Wimbledon has a clear, jarring juxtaposition; on the one hand, a tournament for anyone to enjoy, and yet so much of it is select, exclusive and elitist.

The All England Club is a private members club – and one of only two in the world that holds public tournaments, the other being Augusta – and it has absolutely no intention of changing. It has a board of 12 people, whom Brook describes as ‘covering a variety of skills such as legal, construction and commercial aspects’, but it’s difficult to see it as something for the people. Without wanting to be too judgmental, a look through its board members suggests a level of prestige at odds with their self-proclaimed democratisation; PGH Brook (Chairman), Ms SJ Ambrose, The Lord O’Donnell GCB KCB CB, RM Gradon, TH Henman OBE, IL Hewitt, Mrs AWL Innes, SA Jones LVO, RT Stoakes, AJK Tatum, Miss DA Jevans CBE, The Hon HB Weatherill. There are nearly as many titles as Federer has.

Brook points to the public ballot, and the famous queue for general sale tickets – ‘things we could easily get rid of and do without’ – as examples of the tournament catering to the public. There is truth in that, but as thousands of people queue for hours and hours every day in the hope they might make it into the ground, 3,500 debenture holders (2,500 for Centre Court and 1,000 for Court 1) can choose to take up their guaranteed Centre Court seats, for every day of the tournament, as and when they choose over a five year period.

Debentures are issued every five years, at a cost of £50,000 each. At the end of each cycle, holders are asked if they would like to renew, and if not, they are then reissued. In 2016, at the end of the most recent cycle, it raised £100m. It’s a huge sum of money to do away with, but it does have an Orwellian feeling to it; we can all enjoy tennis, but some can enjoy it more than others.

In addition, the Club’s arm’s length approach to dealings with the Lawn Tennis Association (the LTA, Great Britain’s governing body for tennis) is an issue raised consistently (and by a number of audience members at the Capital Club). There is plenty of talk of British success when Murray is lifting the Wimbledon trophy aloft, but it gets a lot quieter once you start discussing grassroots tennis in Britain. Brook says, ‘We have a set amount of money that we contribute to the LTA each year, but we don’t believe we have the correct expertise to help with all matters and have plenty on our plate running our own tournament’.

When you consider it, Wimbledon, as a business, doesn’t actually have any rivals. It sells a product that no one else in the world does. There are other Grand Slams, but they are held at different times in the year. Even if timings can conflict with the football World Cup it doesn’t stop sports fans watching both. It has an absolute monopoly as ‘tennis’s premier tournament’. It is something that has to be applauded as a business model. As long as they keep the queue, the ticket resales at the end of each day and the old-fashioned ballot, they can continue to up the exclusivity; more prestige, more elite, more select. More corporate suites, members-only restaurants and the continuation of the debenture system. In 2041 they will acquire the freehold on the 90-acre golf course that sits just adjacent to the Club’s grounds. They paid £5m for it over 30 years ago, and the value of it 25 years from now will be eye-watering.

Wimbledon sits atop tennis’s table, deciding who can join them and who they will feed. Its status within the game is practically bullet proof and, understandably, they have absolutely no intention of changing the methods that got them there, elitist or not.