West Africa: Celebrating A Glorious Heritage

One thousand years of West African history and heritage have been brought to the fore in a new major exhibition at the British Library in London. West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song is a mesmerising collection of artefacts and media from the region’s 17 nations. Co-curator Marion Wallace says the idea for the exhibition, which took four years to plan, was to dispel the perception that West Africa only has a tradition of the spoken word.

Literary Heritage

Evidence of early writing can be seen on one of the first exhibits on display. A wooden bowl and lid dating back several centuries from an area that would now be southeastern Nigeria is engraved with nsibidi symbols – a graphic system that was used for general communication. Arabic was also widely used for writing texts, following the spread of Islam to West Africa from the North in the 8th and 9th centuries. Important manuscripts such as amulets, which were popular in pre-colonial times, were written in Arabic. It was believed that the small pieces of parchment inscribed with a blessing conferred power and protection for the owner. The literary culture can also be seen on boards which were used to teach people verses of the Qu’ran. Written in locally produced ink, as one verse was learnt it would be washed off the board and replaced by a new one. The method has survived the over the ages and some children today learn the Qu’ran in the same way. The printing press was brought to West Africa in the 19th century when missionaries arrived in large numbers, and locally established printing enabled the widespread publication of the Bible and its translation into local languages. One of the most intriguing items on display in the collection is the first translation of Bible scripture into Yoruba, the Book of Romans, translated in 1850.

The Importance of Music

The exhibition vividly captures — through a range of audio recordings and video clips — how music, song and performance were vital channels for expression, storytelling, commentary and protest. Excerpts of music by the Maroons – the runaway slaves in Jamaica — and images of dance in the Americas reveal in their style and rhythms how strong connections remained, despite the uprooting from their West African homes and enslavement. Instruments were highly important too. They were symbols of status and power, and drums were used to replicate the region’s tonal languages and communicate across long distances. The drum, or atumpan player, for example, would be responsible for relaying messages from the king. A pair of atumpan, or ‘talking drums’, are included in the exhibit and there is the opportunity to hear how a drum would have sounded, courtesy of a 1921 recording made in Ghana. Another significant musical item is the akonting, and a replica of this now rare stringed instrument was specially commissioned and handmade for the exhibition. It is possible that the akonting could be the predecessor of the banjo. It originated with the Jola people of The Gambia, many of whom were taken to work on plantations in America’s south during the transatlantic slave trade years.

Political Protest

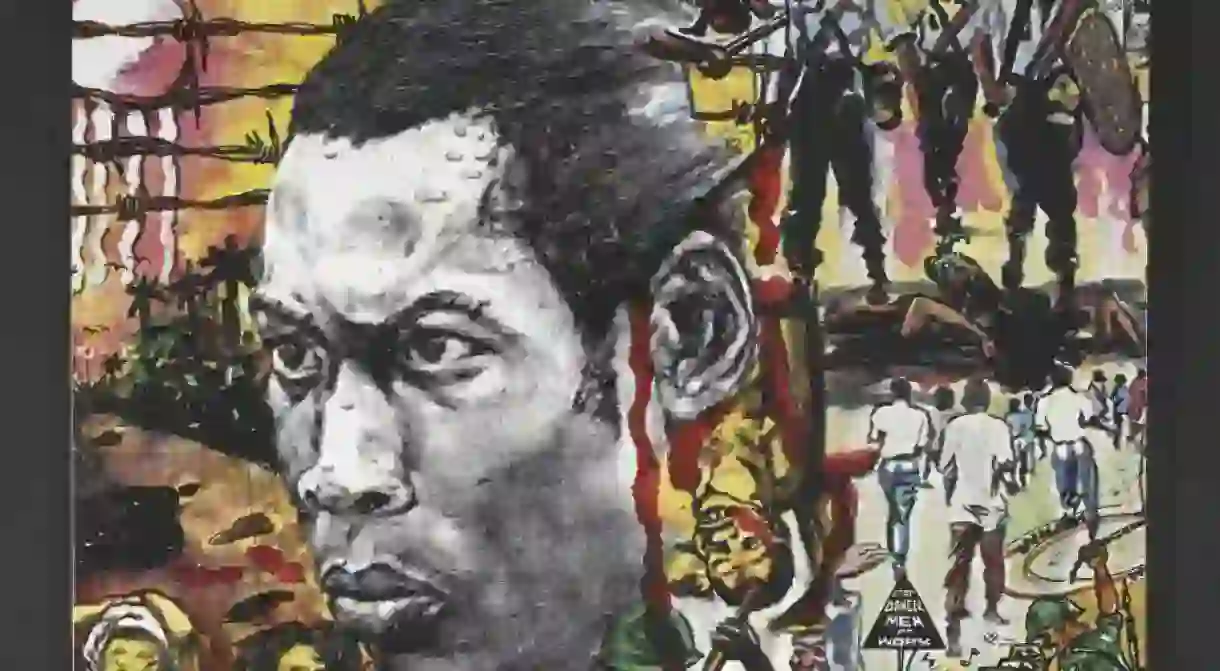

Words, symbols, music and literature became the tools of West Africa’s elites, intellectuals and ordinary people to assert their views and challenge colonialism. The printing press, introduced by the missionaries, helped to facilitate a new critical voice. Pamphlets calling for the rights of Africans and newspapers in different languages began to flourish in the mid-nineteenth century, giving rise to a new pan-African sentiment. As West Africa entered the 20th century, political leaders emerged who fought for independence and an end to colonial rule. Some of their writings or articles are on display, along with cloths with woven tributes and recordings such as Kwame Nkrumah’s independence speech in Ghana. The embodiment of music and performance as revolution comes in the form of Nigerian artist Fela Kuti. His music and outspoken criticisms of civil war — and what he saw as corruption in his native country post-independence — led him to be beaten and imprisoned. A snapshot of his life in video and a letter to General Babangida are among the items on display in a booth dedicated to him, illustrating why he is considered to be one of Africa’s most influential musicians and political activists.

Legacy

In addition to the ‘Fela’ area, the visitor can spend time becoming immersed in two other booths – one featuring footage from the Notting Hill carnival and the other extracts from West Africa’s contemporary comedies and short stories. There are also other activities and a programme of events that are running in conjunction with the exhibition. The West Africa Learning Programme — which offers workshops and resources to schools for children of all ages — is another important strand, and one that Marion Wallace believes will be the legacy. There are no plans to tour the exhibition when it ends in February and many of the items will be returned to the vaults of the British Library. It is anticipated that there may be an argument that the rightful homes of the exhibits are the West African countries that they portray, but Wallace says that countries hold their own collections. West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song gives an invaluable insight into the history of a vibrant region that has shaped societies within and beyond its borders. The exhibition’s millennial history starts with the early writing style of nsibidi, and concludes with perhaps the most appropriate sign of our times. The last item on display is in fact a Twitter post of a poem #benokriwild released, line by line on the digital platform, by Nigerian-born writer @BenOkri.

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song can be seen at the British Library until February 16th 2016.

British Library, Euston Road, London, UK, +44 (0) 1937 546546

By Patricia Whitehorne