The Story Of The Parthenon Marbles

The Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, are one of the must-see collections held by London’s British Museum. Beautiful and iconic, they are given pride of place in the museum and considered one of the collection highlights, but their situation there is not without its controversies. This article explores some of the debates that surround them.

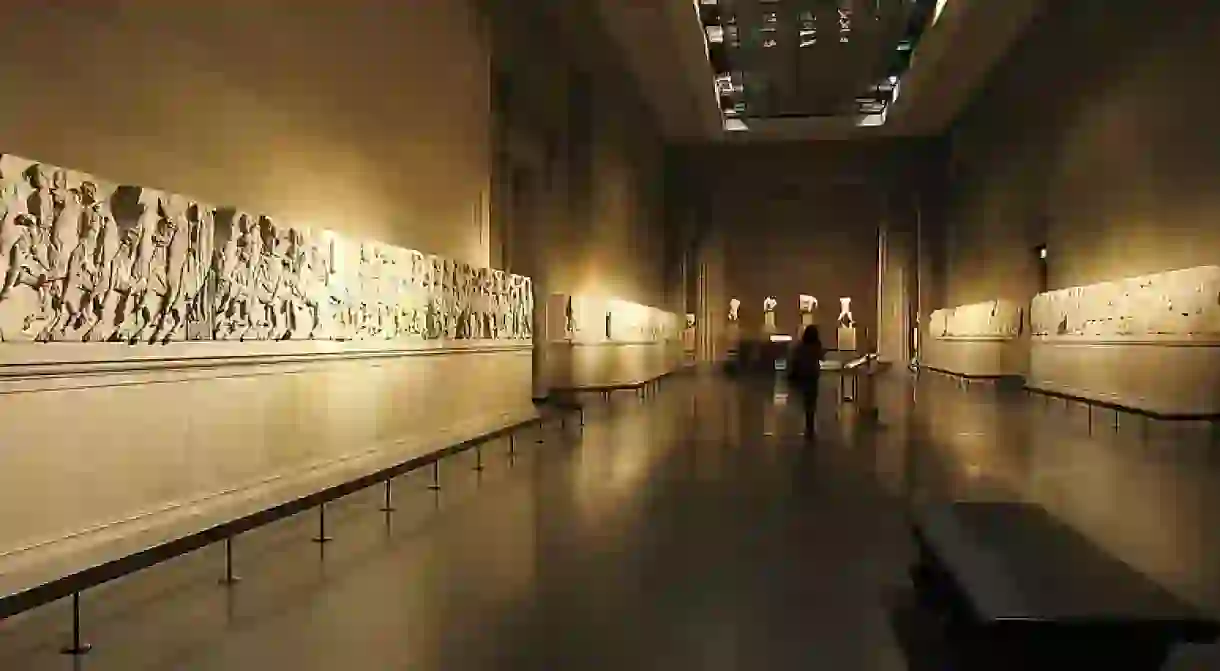

Lining the walls of the museum’s purpose-built, beautiful, light and airy Duveen Gallery, the Parthenon Marbles are regarded as one of the finest and most complete examples of Classical Greek marble sculpture.

The collection consists of a number of pediments and metope panels that depict battle scenes between the Centaurs and the Lapiths as well as part of the temple frieze, all of which once decorated the Parthenon temple on the Athenian Acropolis. The sculptures date from around 432 BC and are attributed to the sculptor Phidias and his assistants, now regarded by many as one of the greatest of the ancient Greek sculptors.

The Parthenon itself holds great importance, not only as one of the most important surviving buildings built in the Classical Greek style, but as a symbol of modern Western civilisation and the cultural identity of Greece. So with the Parthenon still standing, what are these sculptures doing in London?

In 1798, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin — hence the name, ‘Elgin’ Marbles — took particular interest in the Parthenon and began to commission artists to take drawings and casts of the marbles whilst still in place. However, in 1801, Elgin obtained a permit from the Ottoman Empire, who at the time ruled over Greece, to start removing many of the surviving Parthenon sculptures, after which he sent them back to London with the intention of having them displayed in the British Museum. Even at the time, it was a controversial acquisition, with disputes arising over the legitimacy and legality of the removal permit and criticisms of vandalism from Elgin’s contemporaries, most notably from Lord Byron.

But arrive in Britain they did, entering the collection of the British Museum in 1816, where they have remained since. Controversies aside, those in Britain celebrated the arrival of Elgin’s marbles with many admiring their beauty, inspiring a revival of interest in Classical Greek art. 200 years on, this is a debate that continues.

Much of the controversy surrounding the marbles today is based on the same arguments that presided over them in the 19th century; for example, the legality of their acquisition and claims of vandalism to both the Parthenon and the marbles themselves, as damage has occurred since they have been in British possession.

One of the other main arguments for their return to Greece that has emerged is that the marbles were meant as a complete, single work of artwork with specific relevance to their position on the Acropolis, and in Athens more generally. As such, it has been suggested that the marbles ought to be brought back together.

In 2009, the Acropolis Museum opened in Athens, which houses a whole floor dedicated to the Parthenon. This floor contains a reconstruction of the temple, using a mixture of remaining original sculptures and plasters of those taken by Elgin, and has been built with technology specific to the preservation of the marbles. The absence of the original sculptures from this dedicated space only goes to emphasise Greece’s rationale for their return.

There is support from organisations like UNESCO, celebrities like George Clooney, and apparently the majority of the British public for the return of the marbles. However, there is a reluctance to return them, and that’s not just because they are one of the British Museum’s star attractions. Some disputes claim that the acquisition was illegal, whilst others argue that showing them in a museum in London is no different to showing them in one in Athens, as they are still removed from their original setting.

The most compelling argument, however, lies in the precedent that restitution of the marbles would set. If the Elgin marbles are returned to the Parthenon, what does this mean for all other museum exhibits and collections all over the world? Should they be returned to where they came from too? And what then would happen to museums and representations of cultures other to our own?

The marbles are undeniably symbolic of Britain’s colonial past, but then, it could be argued, so is everything else in the British Museum. In this way, they are as much a part of Britain’s cultural identity as they are Greece’s. When it comes to restitution, it still isn’t clear what lines can be drawn.

Cases like that of the Parthenon Marbles highlight the importance of museums, no matter where they are or what they hold. It emphasises that their collections are so much more than dusty relics, but living, breathing players that represent a much wider discussion about culture and who it truly belongs to.