The Most Violent Shakespeare Plays

We all know that Shakespeare loved to indulge in violent imagery and audience-traumatising scenes in many of his plays. The three main genres he wrote were comedy, romance and tragedy — and the tragedies definitely did not fall short of violence; even the milder plays such as Cymbeline, Othello and Julius Caesar still abound in rape, murder, war and suicide. But which of his masterpieces, intended for Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences, was the most shocking?

Please note, some of these video clips contain graphic content.

Romeo & Juliet (first published 1597)

The story of Britain’s favourite ‘star-crossed lovers’ opens and closes with death. Set in Verona, the play begins with the executions of a servant from the Montague family and the other from rival family Capulet due to their street brawl: the play immediately portrays violence resulting from the feud of prejudice that the play revolves around. Tybalt from the Capulet family challenges Romeo to a duel after he sneaks into a ball at their house. Romeo refuses and Mercutio fights on his behalf but with fatal consequences, and accordingly Romeo — ridden with guilt and grief — slays Tybalt. The climax of the play sees Juliet drugging herself to appear dead, Romeo did not know the truth when he hears of her death, and in utter despair takes his own life (after killing Paris, Juliet’s proposed husband-to-be). Juliet henceforth awakens to find her true lover dead, and kills herself to be free of a world plagued with violence and to be reunited with Romeo. Almost all of the characters in the play who are connected to either the Capulet or Montague family are inescapably bound to the violence, which is only resolved when they decide it is necessary to be civil due to the sacrifice the young lovers take. Shakespeare offers a perspective of the unfair and overpowering nature of violence in the world, but also how it ultimately brings a sense of hope and reconciliation.

“Two households, both alike in dignity

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife” (Prologue 1 – 8).

Macbeth (first published 1623)

Fair is foul, and foul is fair with Shakespeare’s play of tyranny amongst kings in Scotland, with violence permeating and embodying the destructive effects of selfish political ambition. After Macbeth informs his wife that three witches prophesied his ascent to the throne, she forces him to kill the current king to usurp the royal title, and consequently they murder other characters who could potentially allow the truth to be known. Macbeth has his friend, Banquo, and Banquo’s family to be slaughtered as they posed a threat to his status, which tragically entails the murder of a child on stage. Lady Macbeth eventually commits suicide because she is driven mad with guilt, and the play concludes in combat with the loyal Scottish nobleman, Macduff, beheading Macbeth. With the word ‘blood’ being used in the text over 40 times, Shakespeare utilises violence in Macbeth as a device to propel the graphic action forward, with manipulated language to show the audience’s preoccupation with the spectacle of brutality.

“Methought I heard a voice cry, Sleep no more!

Macbeth does murder sleep, — the innocent sleep;

Sleep, that knits up the ravell’d sleave of care,

The death of each day’s life, sore labor’s bath,

Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course,

Chief nourisher in life’s feast” (II.II.32 – 37).

Hamlet (first published 1603)

Hamlet sees frequent violent acts occurring in sequential calamity. Set in Denmark, Prince Hamlet is confronted by the ghost of his father, King Hamlet, who informs him that he was murdered by his brother, Claudius, in order to usurp the throne and marry the queen. Thinking that Polonius, the new king’s counsellor, is Claudius spying on Hamlet behind a curtain, Hamlet brutally murders him irrationally. Polonius’ daughter and Hamlet’s love interest Ophelia is driven mad and commits suicide, and Hamlet has two characters executed. A fencing match occurs between Hamlet and Claudius’ son, Laertes, which Claudius has organised. But the blade of Laertes’ sword is poisoned, therefore fatally wounding both Hamlet and Laertes, whilst in the meantime the queen mistakenly drinks poisoned wine, and Hamlet murders Claudius moments before he dies himself. The violence in Scene Four where nearly all the characters are left dead illuminates the violence pervading the whole play, as each action is merely a reaction to a previous event. Hamlet acts as a cautionary tale for Shakespeare’s audiences, as Prince Hamlet’s irrationality pushes the play to its bloody conclusions.

“Does it not, think thee, stand me now upon—

He that hath kill’d my king and whored my mother,

Popp’d in between th’ election and my hopes,

Thrown out his angle for my proper life,

And with such cozenage—is’t not perfect conscience

To quit him with this arm? And is ‘t not to be damned

To let this canker of our nature come

In further evil?” (V.II.63 – 70)

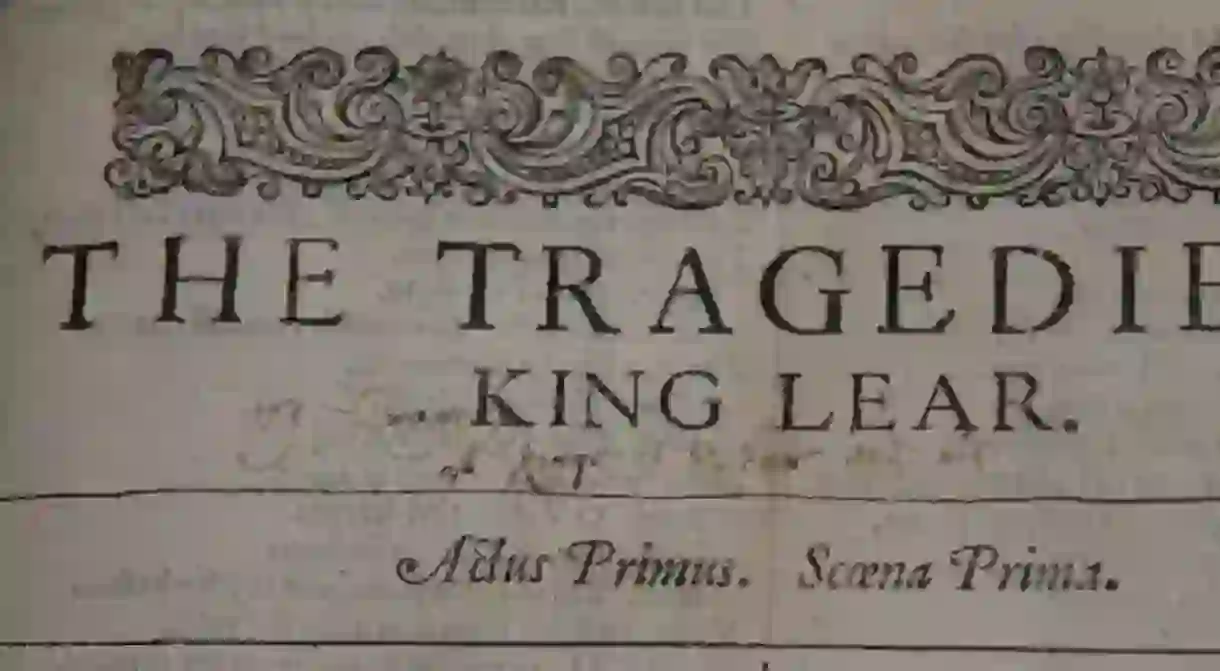

King Lear (first published 1608)

A profusion of gore underpins King Lear, consequently emulating the nature of humanity when concerning suffering, kinship and madness. King Lear decides to divide his kingdom between his three daughters, bestowing the one who proves they love him the most with the largest share. The Earl of Gloucester hears that two of Lear’s daughters, Regan and Goneril, plan to murder the king, so he warns Lear, but the daughters find out, and Regan’s husband Cornwall gouges out Gloucester’s eyes in revenge. A servant tries to help and wounds Cornwall, but Regan slays the servant in response, whereas at this point Gloucester desires suicide and Lear is gradually declining into insanity. Subsequently there is more murder and suicide, armies meet in battle where more blood is shed, Lear’s proven loyal daughter Cordelia is executed, and the king becomes so overwhelmed resulting in his eventual death. Shakespeare may have been alluding to the current audience’s captivation with graphic displays, but ultimately the play proves that despite those who bring suffering are generally brought to justice, those who are completely undeserving also deeply suffer. For many critics of Shakespeare’s plays, all this violence can be widely regarded as a reflection of the nature of man.

“Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones:

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone forever!

I know when one is dead, and when one lives;

She’s dead as earth” (V.III.256 – 260).

Titus Andronicus (first published 1589)

The most violent Shakespeare play of all — so ridiculous it is almost comic — is Titus Andronicus. Set in Rome, there is an absurd amount of unspeakable barbarousness and destruction. The play tells the story of a Roman general Titus, who is committed to the cycle of revenge between himself and Tamora, Queen of the Goths. It is easier to list all the events rather than to describe them; characters are burned alive, arms are cut off, a parent stabs their child to death, there is murder, rape, a character’s hands and tongue are completely severed from the body, there are decapitations, unexplained executions, more murder, and even a mother eating her sons once cooked in a pie. Overall there are 14 killings, six severed members, one rape, one live burial, one case of insanity and one case of cannibalism. This is an extreme case of revenge-fuelled, graphic violence on stage, and it was one of Shakespeare’s least respected plays. Once again, the playwright may have formed this whole setting as a satire, in order to mock the audience that desired to be engrossed in visions of violence. Whereas some may believe this was a naive and distasteful piece of work, many argue that it was an imitation of some of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, who focused purely on bloody revenge. Either way, it is undoubtedly the most gruesome play of all.

“You sad-faced men, people and sons of Rome,

By uproar sever’d, like a flight of fowl

Scatter’d by winds and high tempestuous gusts,

O, let me teach you how to knit again

This scatter’d corn into one mutual sheaf,

These broken limbs again into one body;

Lest Rome herself be bane unto herself” (V.III.69 – 75).

https://youtu.be/gZWq9Ny5TUc

By Stephanie Butler