The Meaning Of Jan Van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), is undoubtedly one of the masterpieces in the National Gallery’s collection. With brushwork so fine the effect seems photographic, hidden details, and playful visual effects, this painting is as visually intriguing as it is famed. It is also an informative document on fifteenth-century society, through van Eyck’s heavy use of symbolism.

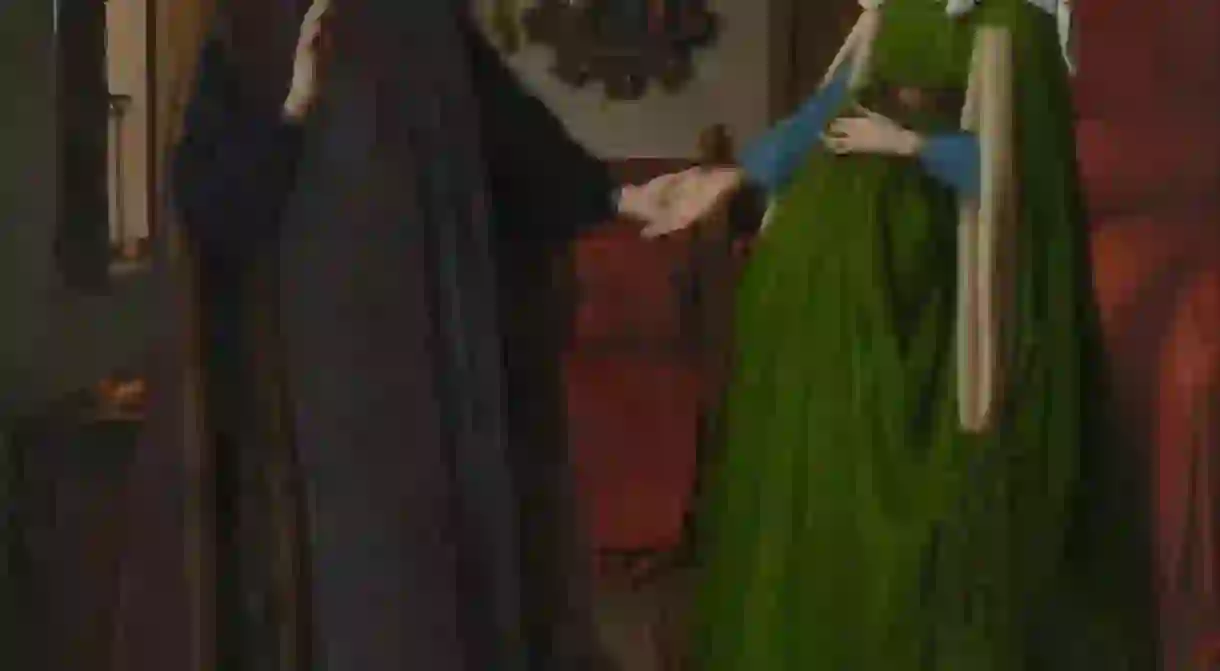

The subject of the Arnolfini Portrait (Figure 1) is domestic: a man and a woman hold hands in an interior setting, with a window behind him and a bed behind her in natural symbolism of fifteenth century marital roles – while husbands went out to engage in business, wives concerned themselves with domestic duties. The clothes the pair are wearing would also have been intended as demonstrative, this time of wealth and social standing. Fur was an expensive luxury permitted by law only to the upper echelons of society, so van Eyck’s patrons and sitters would have been making a conscious statement on their wealth and status by having fur trimmed clothes (particularly as the blooming tree outside the window suggests that the day was warm). The colours of these garments and also of the bed hangings, are also significant: red, black, green and particularly blue were all fabulously expensive dyes, so again would have been intended to show the wealth of this couple, ditto the pure amount of fabric (heavy pleating uses more cloth, ergo clothes with pleats, folds, tucks etc. all cost more). Van Eyck also made sure to include tiny, beautiful details – such as the matching gold and silver cuffs on the couple’s wrists, extensive detailing around the edge of the woman’s veil, and a few highly expensive oranges on the chest beneath the window. These not only demonstrated his own talent for skilled, intricate brushwork, but also the following simple fact: that the couple pictured were not only wealthy, but educated – they knew how their money should be spent in order for it to reflect well on themselves.

This brings us to the question: who were this couple? The male subject to the viewer’s left of the scene is most recently thought to be a Bruges merchant named Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini, and the woman beside him his wife. However, there are several problems associated with the second half of this identification. The artist has clearly written on the painting, in ornate Latin, “Jan van Eyck was here 1434.” However, Giovanni’s wife had died in 1433, which presents the possible hypothesis: van Eyck had begun the work in 1433 while his patron’s wife was alive but she had died by the time he finished it, or it was simply a posthumous portrait. This theory is not unreasonable, and is supported by much of the visual content of the scene: the male figure’s loose grasp on the woman’s slipping hand, and the odd candles in the ornate chandelier – that on the man’s side is still whole and lit, while the opposite candle holder is empty aside from a few drips of wax, signifying that the man’s life light is still burning while hers has burnt out.

There is also, of course the mirror on the back wall of the scene – an object often associated with Vanitas paintings which reflect on mortality and death, clear in Trophime Bigot’s Allegory of Vanity (Figure 2). Posthumous portraits were also not unheard of; in 1472, in Urbino, Italy, Duke Federico da Montefeltro had commissioned a diptych of himself and of his recently deceased wife. The double portrait survives to this day, with the pair continuing to face each other in death and in life, his face tanned and healthy while her face is marble white (Figure 3).

Returning to the Arnolfini Portrait, there is also a second possibility, that this is a depiction of a second marriage, for which the records have been lost. Certainly the woman’s face appears particularly young, almost doll-like – although this youth is no indication that she was a second wife, as girls could be married before they were even teenagers at this time. Her appearance is very fashionable, with a high, plucked brow and specifically styled hair. Scholarship does not seem to think that she is pregnant although she does immediately appear that way, but rather that she was lifting a great deal of heavy, pleated cloth in order to show off her expensive blue underskirt. Of course, this could be a mistake and the cloth could have been simply intended to draw attention to her waist; there is after all, no mistaking the obvious bed behind her, symbolically decked out entirely in red – an inarguable signifier of love, and passion.

The little dog at her feet demonstrates her fidelity to her husband (a classic artistic motif and one notably used by Madame de Pompadour in the 18th century; several of her portraits as the official chief mistress of King Louis XV of France include a small black dog (Figures 4 and 5)) and her covered head expresses that she is a married woman – only the young, the royal, or the immoral would wear their hair loose and uncovered. Her downwards gaze also shows her submission and meek obedience to the man holding her hand. This was the fifteenth-century after all; women were the property of their nearest male relation, and the thought of them doing anything other than concerning themselves with the wellbeing of their house and their family was nothing short of outrageous.

So far so good – all of the visuality is rather un-extraordinary; aside, of course, from the breathtaking detail and glowing command of colour with which the scene is depicted, and the actual attribution of the sitters’ identities. However, there are several curious notes which make this work of realism stand out as particularly interesting. First and foremost, the mirror on the back wall – which, incidentally, could be a work of imagination, as it is significantly larger than mirrors could actually be made to be at this point – which has already been addressed, but not noted for its spectacularly high detailing. In the polished, convex glass surface, surrounded by beautiful miniature scenes of Christ’s Passion, the backs of the couple are reflected – but also, delightfully along with the bright blue figure of the artist himself in order to present a true depiction of the painting scene. Due to the artist’s inclusion, and of his large signature on the wall, the theory has been presented that the work was the equivalent of a marriage contract: the union has evidently been witnessed by the visual inclusion of a third figure, who has also helpfully signed the image in large, obvious script above the mirror to prove his presence. This theory of course would negate that of it being a commemorative portrait of the wife – but because of the absence of any concrete evidence proving either explanation one way or the other, neither can be proven or disproven.

However, this ambiguity rather adds to the charm of this painting and demands that viewers look more closely at the beautiful, detailed workmanship in order to dig out their own ideas and theories about the work from independent visual analysis. Even if nothing but an appreciation of Jan van Eyck’s supreme talent can be concluded from this work, that is surely a satisfactory conclusion to take away from the mysterious Arnolfini Portrait. Perhaps, if its subject was known, with all of its details and intricacies, then the work wouldn’t be half as appreciated or investigated. Its charm lies in the stories and ideas which it inspires in the minds of those who look at it, into it, and dig beneath its surface; an absence of knowledge only adds to its beauty.