Serving Rum Punch With a Side of History

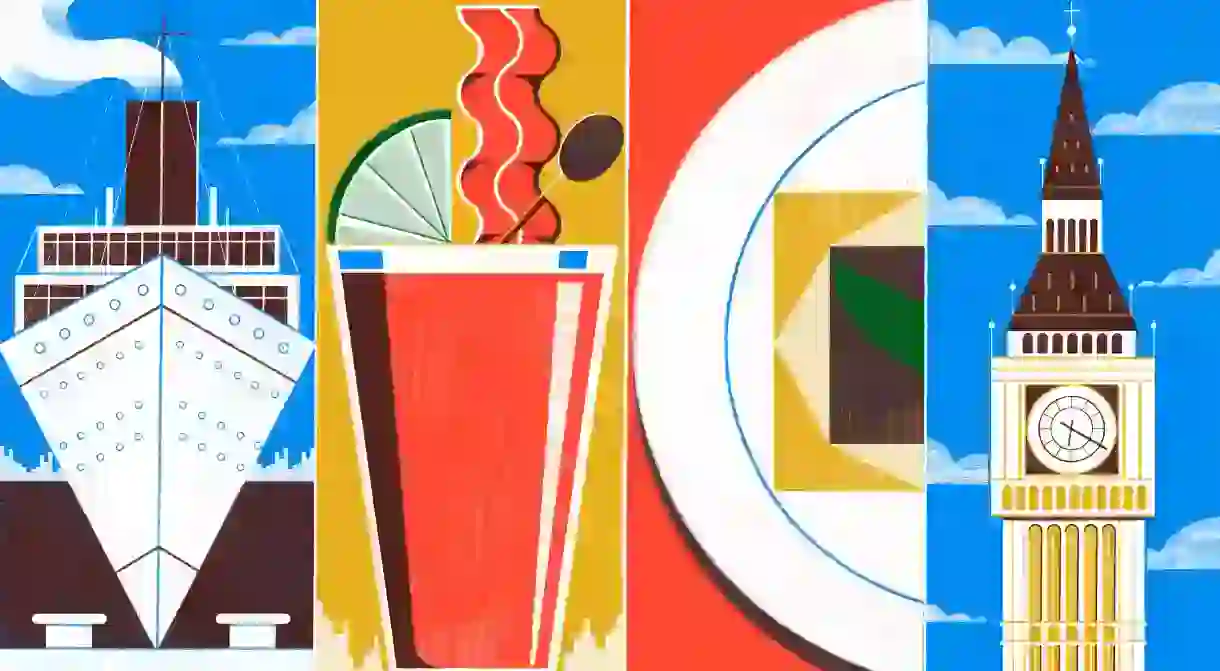

Not only can you grab a tipple and some killer roti at London’s Island Social Club, its founders also hope to inspire Londoners to learn more about the city’s British-Caribbean history.

Even on a rainy Wednesday night, Haggerston’s Island Social Club hums with energy. Fresh rotis, brilliant curries and hand-shaken cocktails pump out of the kitchen as the East London crowd fills the dining room to the beat of a carefully curated playlist.

A collaboration between Joseph Pilgrim of Rumshop and Marie Mitchell of Pop’s Kitchen, ISC is reviving the memory of London’s Caribbean social clubs – venues that rose in popularity after British-Caribbeans began to migrate en masse to England following World War II.

While websites like Black London Histories have mapped London’s Caribbean social clubs to show how integral they were to London’s cultural landscape, it’s an aspect of London’s history that often goes underreported. Much of the information on these spaces continues to exist in the memories of former patrons or in the archives of the West Indian Gazette – a publication founded in 1958 by activist Claudia Jones that covered issues pertinent to black Britons.

The story of these social clubs really starts with the Windrush generation, a moniker that references the Empire Windrush ship which arrived in Tilbury from Jamaica in 1948. Its passengers – all British citizens after the British Nationality Act of 1948 – had left their families and long-standing communities for promised opportunities in the ‘motherland’.

Unfortunately, these opportunities proved hard to come by, and many of the Windrush passengers – and others who migrated well into the 1970s – instead faced blatant racial discrimination when it came to finding housing, employment and acceptance.

For many children of the Windrush generation, London has been shaped by this difficult history, but all the same, the UK is very much home.

“Having grown up in London, I am British first and foremost,” explains Mitchell, who has Jamaican heritage. “But even when you are British and brought up here, you are always the other.”

“It’s important to remember that when the Windrush first arrived, none of the passengers considered themselves ‘Caribbean’; they knew themselves as British. When they came here, they were labeled as ‘Caribbean’ if not ‘black’, which has a homogenising effect on the way people perceive the community,” adds Pilgrim.

This simplification of how British-Caribbean identities are understood can be seen in the current food trend to add ‘jerk’ – a specifically Jamaican style of preparation – in front of almost any dish spiced with a combination of allspice, cayenne and paprika.

Pilgrim notes that growing up, his own understanding of his Caribbean heritage was influenced by a Jamaica-centric perception of British-Caribbean identity: “As a kid, I fully knew what jerk chicken was and owned that it was part of my identity. But my dad is actually from Grenada where the national dish is oil-down.” The Grenadian dish at its most basic is a coconut-based stew with breadfruit and salted meat or fish which Pilgrim describes as “fully delicious, but not ‘sexy’.”

This is a story that is common for people from diaspora communities. “It’s hard to have the chance to drill down into our actual specific cultures unless you have that access through your home, and a lot of people don’t have that access. My dad lives in Grenada now, and my mom, who is white-British, probably knew what oil-down was but it’s not an easy thing to make, so I never had that kind of direct access to the dish,” explains Pilgrim.

At ISC, food becomes the entry point for conversations about the multiplicity of identity, especially with their ongoing supperclub series, Nyammings. Each instalment, called ‘Episodes’, centres on a different theme – 2018 Episodes were titled ‘West Africa to the Caribbean’ and ‘Children of the Diasporas’ – and features a menu curated by Mitchell and a guest chef with cocktail pairings by Pilgrim and readings from a guest poet. The series is meant to draw guests into contemplation about the intersection of food and identity and the diversity of London culture.

“We’re not trying to right the world, we’re not trying to make people have a conversation right then and there. We’re just expressing our modern Caribbean London-ness; it’s not meant to be just about how injusticed the world is,” explains Pilgrim.

In the age of incensed Twitter hordes, it can feel like conversations about identity are inherently polarising. Yet, Mitchell and Pilgrim have created a space for their guests to embrace the beauty and privilege of being able to express and explore identity.

While the Nyammings Episodes allow this kind of interaction every three months, ISC’s residency at Curio Cabal allows for more direct involvement. “It made sense for us to get a space where people didn’t have to rely on tapping into us only every three months. Now we have more of an ability to host more specific events,” explains Mitchell.

Much like their mid-century predecessors, ISC focuses on community engagement to define their programming. “We’re talking to poet collectives, we’ve got local artists that we’re going to feature on the walls. That’s how culture works, right? We curate, but collaborate,” explains Pilgrim.