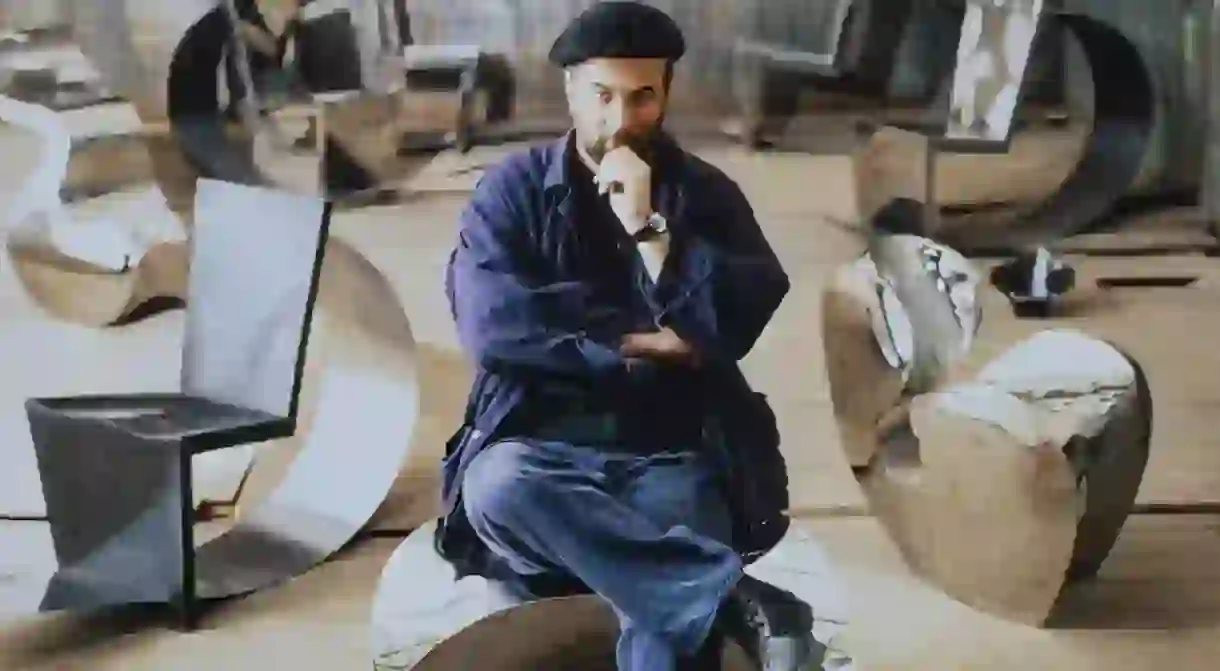

Design Masters: Ron Arad

Israeli designer Ron Arad became an international rising star in the 1980s by defying boundaries and experimenting with cutting-edge materials. His early works are just as relevant today as they were during the punk era, with his radical approach and maverick charm still inspiring a new generation of creatives today. In the first of the ‘Design Masters’ series, he tells Culture Trip how he fell into the rabbit hole of the design world.

Tel Aviv-born designer Ron Arad has made a name for himself as a rule-breaker who tends to do exactly the opposite of what’s expected. Just like his famous bendy shelf design, the Bookworm, he simply doesn’t conform to the industry’s straight and narrow path, refusing to be being pigeonholed as just a designer.

“Architects say, ‘Oh he’s not an architect, he’s a designer,’ and a designer will say, ‘Well he’s not a designer, he’s an artist’ and so forth,” explains Arad. “To me, it means I don’t have an exclusive membership to any discipline. I am all of the above.”

Arad has certainly dabbled. In a 40-year career, he has built museums, designed chairs and made sculptures. Even his latest collection of Concentrics vases for avant-garde glassware firm Nude is typically offbeat and experimental. “I’m lazy, and I’m not methodical. I jump from one thing to the other,” he admits.

Despite his rebellious nature, Arad has been embraced by the very institutions he’s persistently tried to subvert. Feted with huge retrospectives at the V&A in London and the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the designer’s work is featured in permanent collections at places such as the MoMA. His designs are currently on show in Ron Arad: Yes to the Uncommon! at Vitra Design Museum in Germany, which focuses on the crucial, earlier period of Arad’s career.

Arad came to London in 1973 after studying one year of environmental art in Jerusalem (during which time he got arrested for orchestrating a demonstration against a military parade), and merely took a fancy to studying at the Architectural Association, turning up to the interview without a portfolio. Arad graduated from the AA five years later, landing a job at an architecture practice in Hampstead. This didn’t last, however. He simply walked out one lunchtime and never returned.

“It didn’t take me long to realise that it’s really difficult for me to work for other people – more so after lunch,” he says. “I went to a scrapyard behind the Roundhouse instead and had this idea of converting a car seat into a domestic object, inspired by the readymades of Duchamp and Picasso. I chose the Rover seat and shortly after that I set up a studio in Covent Garden, although then I didn’t know for what. It was a very cute place with exotic shops, like a little store by a man called Paul Smith.”

Arad continues: “One Boxing Day I had a knock on the door and I said ‘Sorry, we’re closed,’ then someone said in a French accent, ‘But I want to buy these chairs!’ I said, ‘Ah, we’re open, come in.’ He gave me a cheque there and then for six, which was signed Jean Paul Gaultier. After that, as if by magic, it became my best-selling piece – I think he had a nose for what was coming.”

It’s Arad’s early works, like the Rover Chair, that fascinated Vitra Design Museum curator Heng Zhi. “The early One Off studio pieces are so appealing exactly because of their rawness and heaviness,” explains Zhi. “The rough welding seams, the spalling concrete edges all remind us of the rebellious punk spirit of this period.

“Arad demonstrated a new kind of freedom in the design profession by merging a drawing office, a workshop and a showroom into one studio. He didn’t need to subordinate his work to any clients from the industry or the gallery scene. Instead, he was able to work freely with the least constraints possible from outside.”

Arad realised the design industry was beginning to notice his work when he saw a feature on the director of Swiss furniture brand Vitra, Rolf Fehlbaum, in Blueprint magazine. “There was a picture of him with the Rover Chair and he’d been quoted saying ‘Ron Arad is one of the most interesting designers to come from London.’ I didn’t know who he was at the time, and I didn’t know that I was a so-called designer, so I actually blame him for this, or owe him, I’m not sure which.”

The culmination of the Rover chair’s success was when it went on display at his major monograph No Discipline at the Pompidou Centre in 2008. “I lent them my two Rover Chairs from home that my daughter had jumped on and the cat had given birth on,” says Arad. “I wanted to move one and I was shouted at, ‘Not without white gloves!’ It was then I understood the mission of the Rover Chair was complete – it, and I, had made it.”

After this, other commissions quickly rolled in, including ones from Vitra. Fehlbaum invited him to run an experimental workshop at the museum. Arad asked for rolls of tempered steel and the result was the deceptively springy yet sturdy Well Tempered Chair, made in 1986. Arad also created the concept for the Bookworm shelf out of a thin blade of steel, which now sits on the wall of Arad’s home. It was this design that really threw him into the arms of the masses, as it was one of the first customisable products that allowed homeowners to create any shape they desired, whether it be curved, spiral or, heaven forbid, a straight line.

“Time and time again, Arad succeeds in translating the limited studio editions into objects for the industrialised production,” says Zhi. The Bookworm went on the market in 1993, produced by Kartell in PVC, and to this day it still sells 1,000 kilometres (621 miles) of it every year.

According to Arad, it was these commercial projects that paid for his experimental period, allowing him to create even more radical pieces. One of these is the ‘Sticks and Stones’ machine, which has been restored by the museum and is the highlight of Yes to the Uncommon!.

“It’s like a conveyor belt that you place chairs on and other metal objects, which then fall into a perspex box where they’re crushed, and then it spits a compressed cube out,” explains Arad.

This piece is just as relevant today as it was when it went on display at the Pompidou Centre 30 years ago, according to curator Zhi: “Objects are being scrapped instead of new goods being produced and through this act of deconstruction, Arad questions the designer’s role in our industrialised world and prods viewers to take a critical look at the consumer society.”

Even though this was a period when Arad was at his most subversive and experimental, the designs on display at the Vitra exhibition demonstrate that his work is still utterly contemporary. What unifies Arad’s portfolio and makes him still relevant is his insatiable curiosity for the new, and his unwavering free spirit. Without anyone to tell him no, Arad has been able to say yes to the uncommon, leaving a legacy of radical works that will continue to inspire generations.

Ron Arad: Yes to the Uncommon! runs until October 14, 2018 at the Vitra Design Museum. For more ‘Design Masters’, read our interview with legendary British designer Sir Terence Conran.

Vitra Design Museum

Building, Museum