"A Narrative Around Guns": Gary Younge On His Latest Book

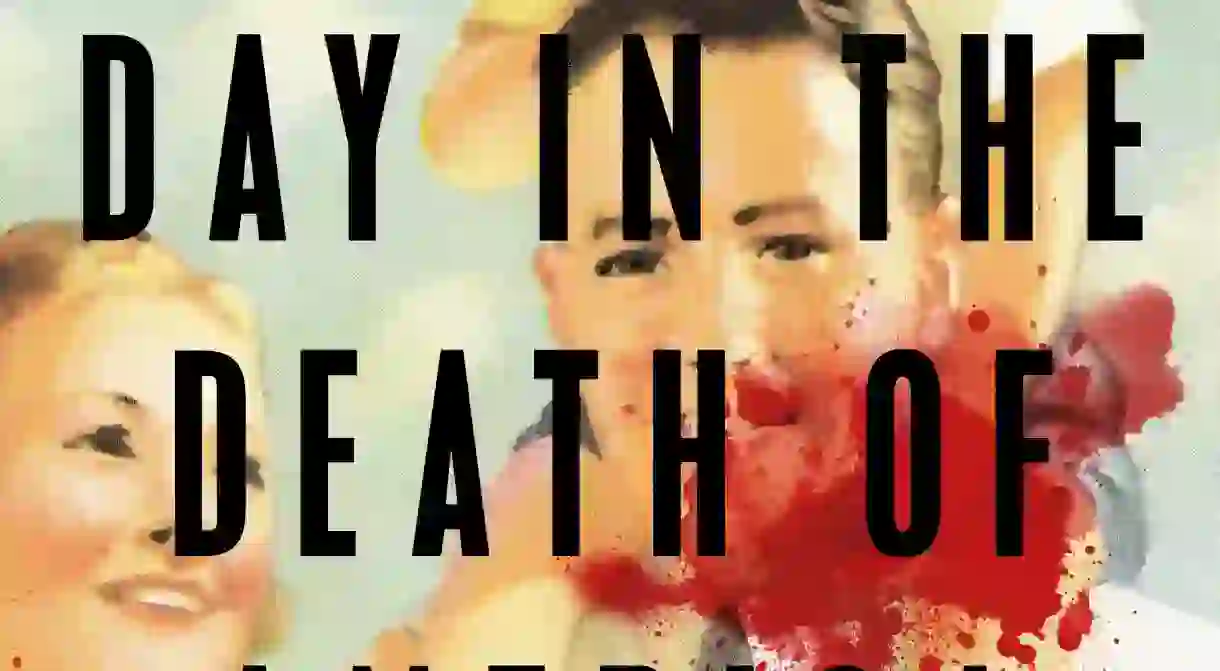

Present at the London Book Fair to discuss Another Day in the Death of America, Gary Younge revealed that the book had been optioned for a feature film, with Chiwetel Ejiofor apparently in the run-in to play him. Just how a movie could be made from a work chronicling the lives and deaths of ten young Americans we’re not sure, but there have definitely been worst ideas.

Published late last year to great acclaim, the book follows the Guardian and Nation journalist around the US as he tracks down, and gives account of, the families of ten young Americans, all shot dead within 24 hours of each other.

Invited by English PEN to have a conversation with Steven Gale, a tweeded Gary Younge began by shedding some light on the reasons why he chose to set his work on a specific day—November 23, 2013: “The premise of the book is that every day in America seven children and teens are shot dead, on average. And so I picked a day, and then my desire was to find out who they were. The day was really the first day I could do. If I’d wanted more death, I would’ve waited until the summer—that’s when more children die, when the sun is shining and they’re out of the house.”

This choice was uniquely influential in the the way the book was structured, since it more or less chronicles the events as they unfold. But it is in its subject matter that it mattered most: Younge understandably didn’t want to pick and choose murders to write on, and the deaths on that day were, as expected, not entirely average. “Really, the tension in the book is that if you’d picked a different day, you get a different book,” he opined, “in a macabre sense, I might have waited for a toddler shooting (there’s two of those a week).”

“But here’s a way in which the day is not typical: racially, of the seven children killed on average, three would be black, three would be white, one would be latino, and an Asian or Pacific Islander or a Native American would be rotated in once every three days. On this day, seven children are black, two are latino, one is white.. so it’s disproportionately black. That’s the first thing. On an average day, of the seven children shot dead, two would be female; on this day it was ten boys. And finally, on an average day, of the seven children who are shot dead two will have killed themselves. Now, I did not even go after suicides, because they’re not reported… and that felt like an intrusion too far. And so I know for sure that there were more children who were shot dead that day.”

Why children? “Two reasons, really… First of all, on a strictly authorial sense: seven is a manageable number. I think it’s something like 80 Americans are shot dead every day? That would not work as a book… and then you would start picking and choosing the ones that you want to. But there’s also something about… by the time someone is an adult, one can argue that they’ve written their own script, made their own decisions. But there’s something particular about children that we collectively understand as a society. We are responsible for the well-being and upbringing of children. And so the youngest to die that day was nine, and nobody is going to argue ‘well that nine-year-old knew what he was doing, he had it coming’ or whatever… While we can talk about personal responsibility in relationship to these shootings, there is an understanding that there is collective responsibility for children.”

Innocent victims. “I was trying to be careful there… What I don’t want to convey: ‘children are the fluffy ones, and they are the ones that we should care about’. We should care about all the children that are shot dead, so I do prioritize in the book this notion of… people talk about ‘angels’ and ‘innocents’ and so on, and so there is this sense, particularly with African Americans kids… you will see in headline: ‘He was an A student’, you know, as if that makes the shooting worst. So if he had a B, or a C+, then maybe there was something else going on… And the date of the book is a couple years after the shooting in Newtown, which did energize America’s imagination. And when I asked people why they said, ‘because it wasn’t on the South side of Chicago, it was in Connecticut, they were children, they were innocents, they were angels.’ And therefore that’s what it would take to get the nation’s conscience pricked.”

“But, you know, by the time most people get to 18 or 19, they’ve done something that could count them out of being an innocent. And if you happen to be growing up in a poor and black, or poor and latino area, then almost by definition, just because of where you were shot, people will say: ‘well that was gang-related’. But that’s like saying this event is ‘book-related’, if you’re in a certain area in American, then everything is gang-related because that’s how the country doesn’t work.”