Interviewing Fergus Fleming, Editor Of Ian Fleming’s James Bond Letters

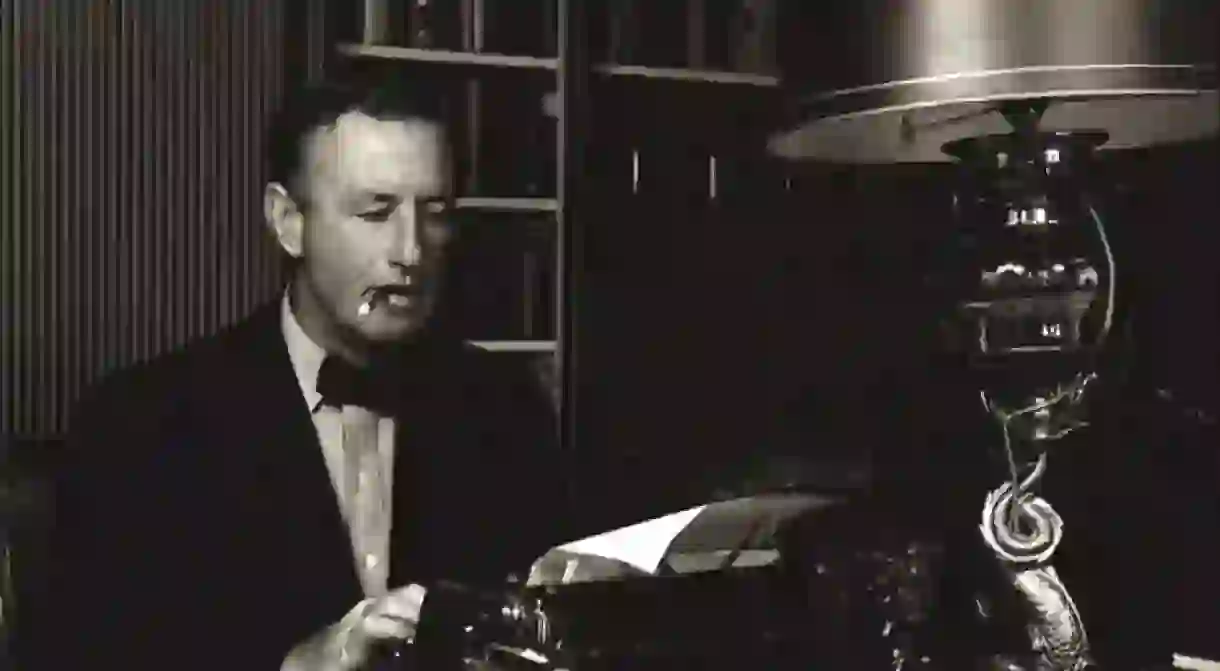

The Man with the Golden Typewriter is a collection of letters written by the highly acclaimed author of the James Bond series, Ian Fleming, sourced by his nephew Fergus Fleming. Fleming’s collection features letters to his wife, publisher, editors, fans, critics and contemporaries such as Raymond Chandler, Noël Coward and Somerset Maugham, reflecting on the progress of the Bond novels. We speak to Fergus Fleming about his inspiration, his uncle and all things Bond.

What inspired you to write this book?

The idea had been around for a while but seemed to be going nowhere. Perhaps rashly, I raised my hand. Even more rashly the offer was accepted. Thus began a slightly unusual yet consistently entertaining voyage into the world of James Bond. Not the Bond of the films, I should add, but the rather different Bond of the original novels and more particularly the mind of the man who created him, Ian Fleming.

How does this compare to your other works?

My previous books have mostly been narrative non-fiction – that is, telling a decent yarn while sticking strictly to the facts. This task was slightly different. While the chapter introductions have a narrative component their purpose is to provide background context, leaving Ian to take centre stage. Each chapter follows the chronology of his output. The result, to my surprise, was not so much a standard ‘Letters’ as an autobiography of sorts. While there have been many excellent biographies of Ian, this is him in his own words.

What was the most fascinating or shocking thing that you found from examining your Uncle’s letters?

Almost every aspect of Ian’s life has been examined, exaggerated, condemned and glamorised to death, so there are few shocks. It was perhaps surprising to find that he received a death threat from a reader who found Bond a threat to civilisation. Offhand I can’t think of any author in the 1950s who received such an accolade. It was also surprising to appreciate just how much time he spent abroad. His love affair with Jamaica is well-known – he wrote the Bond novels at his house Goldeneye – but less generally appreciated is what a fine travel writer he was. Of the many places he visited I particularly like his description of the Seychelles, then set like a forgotten colonial jewel in the middle of nowhere (three days by ship from Bombay.) Its regime was bizarre: nobody was allowed to carry more than two coconuts at a time; the clock struck twice at midday in case people didn’t hear it the first time; and possession of a stingray’s tail was forbidden unless bound as a walking stick no more than three feet in length. Echoes of his stay found their way into his short story, The Hildebrand Rarity.

The most fascinating thing about Ian’s letters, however, is that while he has garnered a reputation for being a suave, high-living, real-life version of Bond, it doesn’t show. Instead he comes across as a polite, considerate and charming man who worked hard to make a living the best way he knew: through his words.

Do you have a favourite letter or story from the book?

Ian’s correspondence is full of good humour. I particularly like his letter to Mrs James Bond. Her husband had written a book called Birds of the West Indies which Ian had by his side at his Jamaican home Goldeneye. He thought James Bond was the perfect name for a secret agent: plain, straightforward and anonymous. In fact, the real James Bond was a well-known ornithologist, famous for his adventures. Mrs Bond caught up with Ian in 1961 and asked what was going on. He replied: ‘I will confess at once that your husband has every reason to sue me in every possible position and for practically every kind of libel…In return I can only offer your James Bond unlimited use of the name Ian Fleming for any purposes he may think fit. Perhaps one day he will discover some particularly horrible species of bird which he would like to christen in an insulting fashion that might be a way of getting his own back.’

What are your most poignant memories of your uncle’s novels?

My memory of Uncle Ian’s books is this: a set of wittily-inscribed editions that sat on a shelf above the telephone. His brother Peter’s were there too. No great fuss was made of them. It was just an accepted fact that members of our family were writers.

What do you think of the evolving re-imaginations of Bond characters, with regards to ethnicity and gender?

Eon have done an excellent job of evolving Bond through the ages. I can’t think of a single Bond who hasn’t fitted the role. As to ethnicity and gender, Ian envisaged Bond as a blunt instrument whose loyalty was to the Crown. That seems a pretty inclusive job description. But my remit is limited to the books. Whatever happens in films to come, Ian’s novels will always remain the classics they are.

How would you describe the book in three words?

Witty, interesting, fun.

The Man With The Golden Typewriter is out now.

Interview conducted by Gina Chahal