Here’s What Happened When Ben Okri And Jeremy Corbyn Met To Talk Literature

‘The most authentic thing about us is our capacity to create, to overcome, to endure, to transform, to love.’ These were words quoted by Jeremy Corbyn in his victory speech after he was unexpectedly elected leader of the Labour Party last summer. The man who wrote them, Man Booker Prize-winning Postcolonial author and poet Ben Okri, penned a new poem in response, “A New Dream Of Politics,” inspired by the politician. This past July, in an event seven months in the making, they came together publicly for the first time in London to discuss art, creativity, and their dreams of a better world.

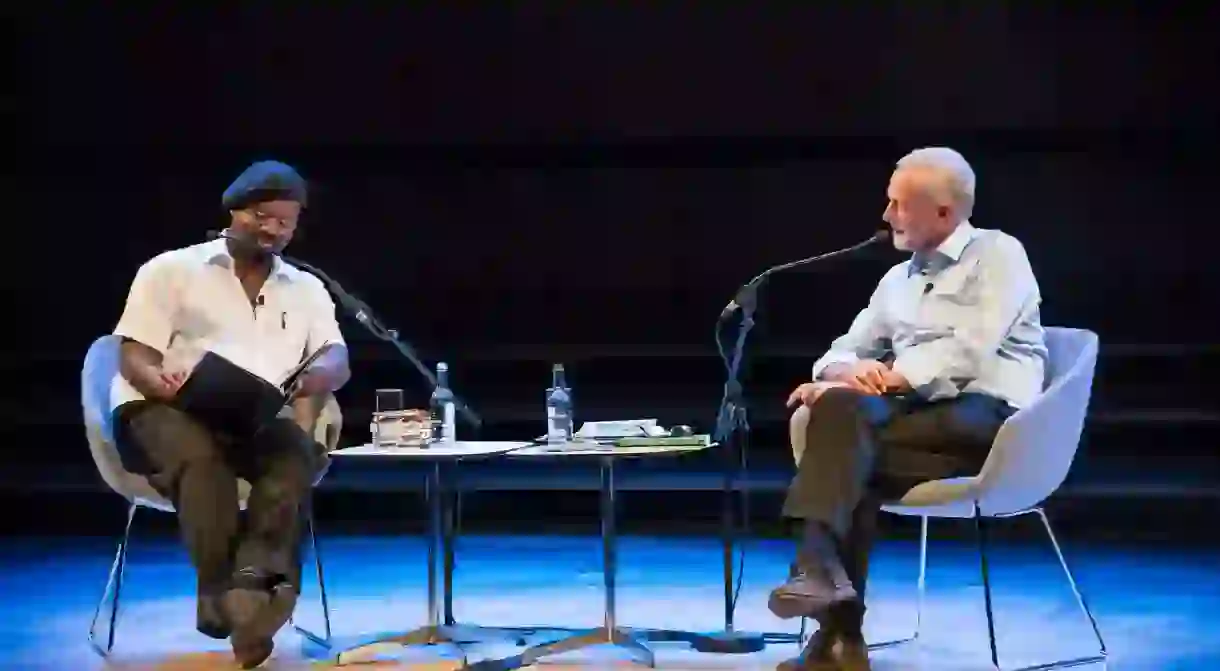

It’s a fairly surreal experience, sitting in the beautiful 2,500-seat concert hall at the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall, watching poet and politician meet to discuss life’s big questions. The evening kept to the loose form of an interview by the former of the latter — loose enough to retain the sense of authenticity so well noted in each, but for which they are far from equally celebrated. In front of each man sat a pile of papers and books, favourite texts selected especially by each from which they would intermittently give readings. The event certainly presented an unorthodox combination, the two arenas — politics and art— seemingly worlds apart. But, as the Southbank Centre attests, this is a place that has always celebrated ‘the transformative power of art’.

Okri began by pledging his intention for the discussion to try and focus on the topics of creativity, literature, art and culture, with the pressing politics of the day — which, he admitted, has dominated all of our thoughts for the past few weeks — to take a backseat. But then again, he told us, he had always found that what you deeply want to talk about will come through anyway. This was proven true almost instantly, when he began to quizz Corbyn on the formative books of his childhood years — his mother, he answered, had given him Robert Tressell’s The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists to read when he was 16, which became a favourite — which quickly descended into a discussion on the implicit political dimensions of such childhood classics as The Little Prince and Alice in Wonderland, with their anti-monarchist motifs and probing of the nature of power.

It’s this fluidity between literature and politics which underpins the poignancy of the meeting between these two men, both extraordinary figures in what seem like two very different worlds, but whom have far more in common than might be initially supposed. In reality, the pairing between the political and the cultural, which Corbyn and Okri’s union represents, goes way back, the two intertwined in an ancient and symbiotic relationship — as Okri himself alluded to in one of his readings of the night, from the poem he penned in celebration of Corbyn’s victory nine months ago:

[…]

‘We measure the deeds of politicians

By their time in power.

But in ancient times they had another way.

They measured greatness by the gold

Of contentment, by the enduring arts,

The laughter at the hearths,

The length of silence when the bards

Told of what was done by those who

Had the courage to make their lands

Happy […]’

A New Dream of Politics, Ben Okri

While this passage alludes to the relationship between bard or songwriter and the deeds of rulers in ancient history, we can look far closer to home for other examples of the link between politics and art, specifically to the rise of democracy in the Western world. In 1831, the French aristocrat and political thinker, Alexis de Toqueville travelled to America, seeking to get a sense of American democracy and equality, to understand how it could be possible to achieve the two principles without the need for bloodshed. His conclusion was laid out in the landmark text Democracy in America, which described how the revolutionary spirit of political democracy and equality had been absorbed into the cultural and artistic landscape of the country.

This was a notion wrestled with by writers from the German Friedrich Von Schiller, who laid out his vision of a democratic art in On the Aesthetic Education of Mankind in 1794, to the British William Ruskin in The Stones of Venice, which pondered on the political dimensions of architecture and design, and was to become a point of fascination for Modernist writers such as E.M. Forster and James Joyce. The central thesis tells how, if democracy is to be more than a buzzword, it must go beyond a simply bureaucratic definition, and be more than just a political apparatus. It must weld itself indivisibly to the very heart and soul of society — and this means it must have its basis in culture.

It is in the spirit of this rich history of cultural crossover between politics and art that Okri and Corbyn confer. Outside the Royal Festival Hall sits a monumental bust of Nelson Mandela, a political figure who famously used poetry and literature to elucidate his cause and inspire support, even using a poem in his very first speech to the South African parliament after his election as President. It’s a fitting link to the man inside, Ben Okri, a giant of postcolonialism — perhaps the most democratic of any genre, in its desire to empower and give voice to the disenfranchised and dispossessed —whose work has always been profoundly political. Okri began writing aged 16, producing political and social articles which were never to find a publisher, but on which his first published short stories were based.

The postcolonial was to serve as an undercurrent throughout the evening, an area of interest shared by both men. Though he was born in Nigeria, Okri was raised in London until he was nine, at which point he and his family returned to their home country. Here he was to experience first hand the violence and tragedy of the Nigerian Civil War, a deadly three-year conflict that saw two million civilians die of starvation and disease, which arose largely from the ethnic and religious tensions stoked by the British during the move towards decolonization. As with many postcolonial authors, his early work was inspired by this political violence. Seeking common ground, Okri questioned Corbyn on the origins of his political activity, particularly his long-documented interest in race relations and identity politics. In 1984 he was even arrested during a protest against Apartheid outside the South African Embassy in London.

After leaving school with few qualifications, Corbyn recalled how he had travelled to live in Jamaica for two years, working with Polio-stricken children and doing campaign work, before getting a job as a Lighting Technician in the Barn Theatre in Kingston. Corbyn explained how, during the 60s, Jamaican theater had been undergoing a remarkable transformation, with the domination of imported British culture beginning to be countered by home-grown texts — Barn Theatre was amongst the first to produce Jamaican plays. The writings of the prominent Pan-Africanist writer, Marcus Garvey, had recently been coming back into fashion, with Corbyn also recalling his experiences of the Rodney Riots, in which the Jamaican government’s banning of Guyanese academic Walter Rodney from the country sparked a period of unrest. As Corbyn put it, at first nobody had heard of the socialist political activist, but rioted anyway. By the time it was over, everybody had heard of him: the government unwittingly triggering a rise in political consciousness across the Caribbean.

It was this formative spirit of counter-culturalism that would inspire an interest in postcolonialism and black consciousness in the future politician, a political awakening similar, in many ways, to that of Okri’s — despite their disparate roles as observer and protagonist, in racial terms at least. While it would inspire a lifetime spent in public service for Corbyn, it would also lead to a lifelong interest in populist art and ‘outsider’ voices across the board. It’s an idea brought to British shores by his reading from a text by his late friend, the poet and social observer Mike Marqusee. Named Street Music, the work is a collection of over 60 poems, which weaves together a myriad of London voices. The poem selected by Corbyn is narrated by a busker, who proudly purports to ‘take the piss out of Intellectual Property’ with his ‘impure’ music, which is regarded with suspicion by others. It speaks to the dynamic between the determined and the determiner, the impotent and the empowered; commenting on the domination of the homo over the hetero-geneous, and ultimately asserting the need for democratic representation to go beyond the empirical and political, to the cultural.

That’s all very well, but what is the purpose of a culture that calls for this if the political class is not engaged? As Okri puts it, a Tango teacher once told him the leader can only lead if the follower follows. Perhaps meant more as a comment on party politics, the anecdote provides a compelling link to the overarching theme at play — the current divorce between the governing body and the cultural life of the society it purports to serve.

‘I don’t know if it’s a healthy thing to meet too many politicians,’ quipped Okri towards the start of the night, ‘The few that I’ve met…they’re not big readers’, a reality Corbyn puts down to the fact that politics today ‘is dominated by process, not by ideas’, and ‘the instant, not the long-term’. Having proven himself a bit of a book-worm, Corbyn described how he uses literature in his life as a politician, reading books that focus on something different to whatever is occupying him professionally. ‘What you’re doing on any day seems very important, like it’s everything,’ he said, recalling how he read Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis and the works of William Godwin on the campaign trail last summer, in order to keep himself grounded in the big picture.

‘From the moment people are elected to public office’, he continued, ‘they are inundated with business-like information and short-term decision making’ — in short, they are taught not to be creative. How, then, to put the creativity back into the process? Corbyn seems to think the route of the problem lies in education (‘why do we separate subjects in school?’), a view Okri enthusiastically endorses. ‘Creativity is fundamentally human’, he argues, ‘so why should we separate things? There’s mathematics in poetry, and poetry in mathematics.’

Beneath all the talk of the evening, sits this incumbent belief in the value that art, with its ability to foster the qualities of innovation and imagination, can offer politics and politicians — which, each man argues, are impoverished by the separation. ‘Is there a spiritual side to socialism?’ asked Okri at one point. ‘Absolutely’, Corbyn replied. And at the heart of their discussion, this seems to be what they are both calling for, the reconciliation of the spiritual with the empirical, the cultural with the scientific, of lateral and vertical thinking — and in their new dream of politics, this is something that only art and culture can bring.