George Skeggs Remembers 60 Years of Late Nights and Lazy Days in Soho

If there’s a single character alive today who epitomises London’s Soho, it’s George Skeggs, who arrived 60 years ago and has frequented the area daily since. His memories paint a vivid picture of London during the 20th century.

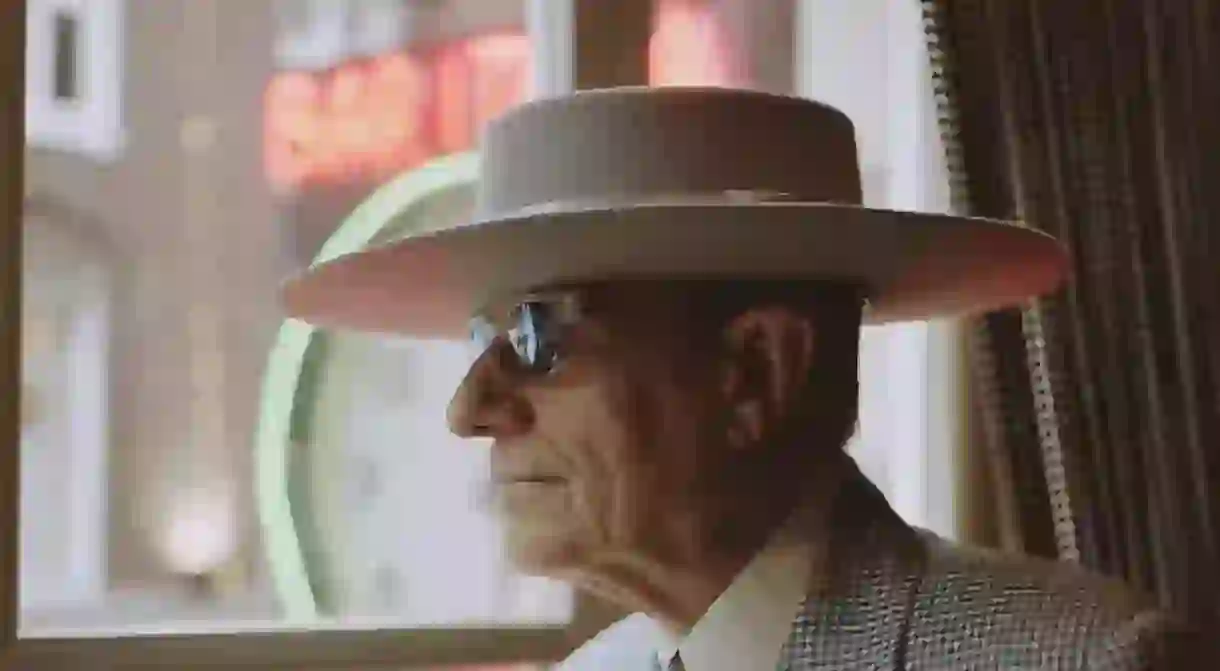

Decked out in his signature blue checked suit, topped and tailed with a fedora and bowling shoes, George Skeggs is an unmissable sight on the streets of Soho. A self-described outsider, the colourful 75-year-old arrived in the area aged 15 and has been part of the furniture ever since. Today, residents call him the “soul of Soho”, owing to his daily presence in the coffee shops and restaurants of Old Compton and Frith Streets.

“The first thing I noticed was the smell of argon in the air – and the noise,” he recalls of his arrival. “It was a new world to me and my friends, but we were immediately hooked. It became our playground. I’m a non-conformist and an individualist. We were all outsiders, but the term ‘outsiders’ can include a lot of people.”

It was the 1956 launch of 2i’s Coffee Bar on Old Compton Street – and its promise to bring American rock’n’roll musicians to London – that first lured Skeggs and his friends to the area. Thirsty for music and attracted by the bright lights of the West End, the group epitomised London’s energetic post-war youth culture. Skeggs talks fondly of the coffee-bar scene at the time, which comprised bohemian establishments that stayed open late and welcomed live music acts – both established and emergent. Among them was Joe Moretti, whose dramatic guitar solos on 1960 hit single ‘Shakin’ All Over’ originated in the basement of 2i’s, and a young, undiscovered Cliff Richard. The original 2i’s neon-lit logo still shines on the walls of what is now Poppie’s Fish & Chips.

“They used to call us the Coffee Bar Cowboys,” says Skeggs. “1958 to 1961 was my era. I drove around on a 150 Vespa wearing French and Italian clothes.” He speaks proudly of his personal style both past and present, and claims to be the person his peers asked for tips on where to shop, but says he never gave away his secrets. His confidence sits somewhere between intriguing and cocky, and it paints a picture of his younger self.

It was the start of the Swinging ’60s. Carnaby Street’s first menswear tailor, John Stephen, had broken the industry and Mary Quant’s modern designs had injected frivolity into women’s fashion. Together the designers sparked London’s fashion revival and the city came alive with expressive style and new music. Skeggs was in the thick of it: “We were the original rockers. We weren’t mods; we were ‘modernists’,” he says, keen to distance himself from anything too stereotypical of the time.

Skeggs remembers a bottle-green jacket with a belted back and two button fastenings that filled him with pride, but says it’s not something he would consider wearing today – his style has evolved with the times. His signature look comprises a longline, draped double-breasted blazer in a bold checked pattern, bespoke headwear and customised details. He still visits local tailors, each of whom knows his specific measurements and quirks: “I go to Berwick Street for my tailoring, and [formalwear specialist] Mark Powell makes my shirts,” he says.

But Skeggs is no mere customer. “Mark Powell picked me out as being the best dressed man at the Soho Fete one year,” he remembers. “I was wearing a peacock-blue-flecked suit.” The fete is an age-old tradition that captures what makes Soho special. Taking place in the summer, it welcomes live acts, street-food stalls and hosts the famous Waiters’ Race – an event that sees waiters carry trays of champagne through the streets – which was originally used as a way of raising money for local businesses.

Berwick Street, which is best associated with music, celebrates Record Store Day with an annual festival in a nod to its age-old reputation. Enthusiasts still gather to bolster their collections, but it’s a dying trade as boutique stores suffer the rise in rent prices and technological advances. “The biggest change between then and now is that everyone walks around with headphones in,” Skeggs observes. “Where’s the live music? Where’s the atmosphere?”

Jazz After Dark, which opened in 1985, is one of modern-day Soho’s few establishments truly reminiscent of the era that Skeggs remembers. The cocktail bar and gallery was a preferred drinking spot for the late Amy Winehouse, and the walls are decorated with her portraits, each painted by the owner. A former artist himself, Skeggs talks admiringly about the work. His own creations, which are expressive, freehand explosions of colour, can be found on the walls of some of his favourite local haunts, including Tony Phillips Tailoring & Alterations, which he visits almost every day.

“Creativity is in the ozone here,” Skeggs says. “It’s places like this that prove some of Soho is still alive.” He names rustic café Bar Italia as a favourite haunt. Its unaltered atmosphere and way of working capture the gritty charm of the past that he romanticises. “But these are troubled times,” he continues. “There are a few hidden gems but mostly you look down the high street and it may as well be Basingstoke.” His emotional ties to the past are clear, but Soho’s history is steeped in debauchery as well as prestige – perhaps the lines between fact and fiction have blurred over time? “Everyone did business in coffee bars like Bar Italia surrounded in clouds of smoke,” he remembers. “I still visit it each day.”

Skeggs remembers the late 1980s as being the most significant era for change. “I don’t remember much between 1980 and 1985,” he says. “I lived a very hedonistic lifestyle.” Fast-forward to the latter half of the decade and the strip clubs that fuelled Soho’s nightlife had begun to close. “Prostitution was a huge business – there were brothels above every coffee bar,” he says. There’s little by way of opinion to his statement; instead, he’s talking factually. His unemotional approach drives home the unnerving normality of the industry at the time. He recalls the railings under the arches at Piccadilly Circus as being a notorious pick-up spot, nicknamed the Meat Rack. “There was a 24-hour cinema on the corner of Piccadilly that got itself a bad reputation. It only cost a shilling to get in and eventually they had to turn the lights on during the shows because of people ‘doing business’ in the back row,” he says.

Gun crime was also rife, with underground bars providing a safe space to conduct illegal exchanges. “I remember the Log Cabin club feeling like a villainous place,” says Skeggs. “It was like a job exchange for villains, a black-market hotspot. I only went in once. Some things did need changing – it was a bit old rep.”

These days, Skeggs starts his day at 1pm at the British Museum, where he once worked. After a browse and a cappuccino, he takes the same route down Denmark Street and Greek Street towards Bar Italia where he stops by to “chat to the boys in there”. Then, it’s a short walk to Berwick Street to visit tailor Tony Phillips. It’s here that Skeggs seems happiest. Carnaby Street is too commercial now, he says, but Berwick and Old Compton Streets “used to be edgy and a bit sleazy. [They] had character”.

It’s this set daily routine, stand-out sense of style and charisma that make George Skeggs such a recognisable face in Soho. His passion for the area is clear, despite its many changes. “If you live in London, you’re laughing, aren’t you?” he says. “It’s the golden triangle. You’ve got everything here. I’m lucky because I can walk everywhere within 15 minutes and I’ve been enjoying that luxury for 60 years.”

Our debut short film, The Soul of Soho, explores neighborhoods separated by oceans, history and culture but united by craft community and change. Neighborhoods bound by one name: Soho. Intimate portraits of city living in the Sohos of London, New York and Hong Kong reveal rich stories of the people who bring life to these iconic neighborhoods. Explore Soho here.