A Stroll around Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square

Hangover Square is often described as a comedy, even a hilarious one, but the overriding impression it gives is of bleak and tragic terror. The masterpiece of the criminally overlooked Patrick Hamilton, it tells of the story of George Harvey Bone, a big, good-natured and pathetically misguided man whose daily life is spent drinking himself quietly into a stupor in the smoky pubs of Earl’s Court, West London. Indeed, the novel is sometimes subtitled A Tale of Darkest Earl’s Court.

Hamilton’s depiction of a drinker’s London in 1939 — dirty, soaked with gin, and weighed down by the threat of an oncoming war — is one of the novel’s many masterful strokes. Earl’s Court is a seedy, slow-moving trap; Bone sits drinking steadily in these darkened pubs and listens to the opinions and boasts of the Nazi-supporting Peter and the aspiring actress Netta Longdon, for whom Bone has a chronic and mercilessly one-sided infatuation. They are sociopathic, unsympathetic and cause Bone no end of misery, but his obsession with Netta makes it impossible for him to leave: the few times he escapes the pull of Earl’s Court and alcohol, to the relatively upmarket restaurants and clubs of the West End or the peace of Brighton, he soon tumbles back in a drunken haze of wounded pride, waking in the morning to take a regretful, self-flagellating ‘stroll around Hangover Square’ (the pun refers to Hanover Square in Mayfair – confusingly distant from any of the novel’s settings).

The images of intoxication and the subsequent hangover extends into Bone’s ‘dead moments’, times when ‘something goes click’ in his head and he finds himself cut off from a world that seems suddenly distant, blurry and false – as if he, even in this deadened state, is the only thing that exists. Hamilton characterised these moments as being indicative of schizophrenia, which – while medically dubious – is an effective literary device, for it is in these dead moments that Bone is finally able to see that it is his infatuation with Netta that is causing all his problems, and he resolves to kill her and escape to Maidenhead in Berkshire. In his head at these times, Maidenhead appears as a heavenly, idyllic answer to everything – he will stop drinking, and we will escape the misery of his association with Netta and the smoky rooms of Earls Court. Then, as swiftly as it appeared, the dead moment vanishes, leaving Bone with no memories of murder or Maidenhead. The dead moments may not be caused by alcohol, but there is certainly something of the hangover in Hamilton’s description of them; the familiar haunts of Soho and Earl’s Court become incomprehensible and impossible to deal with during these times, evoking how hostile the more raucous parts of London can seem to the exhausted and disoriented.

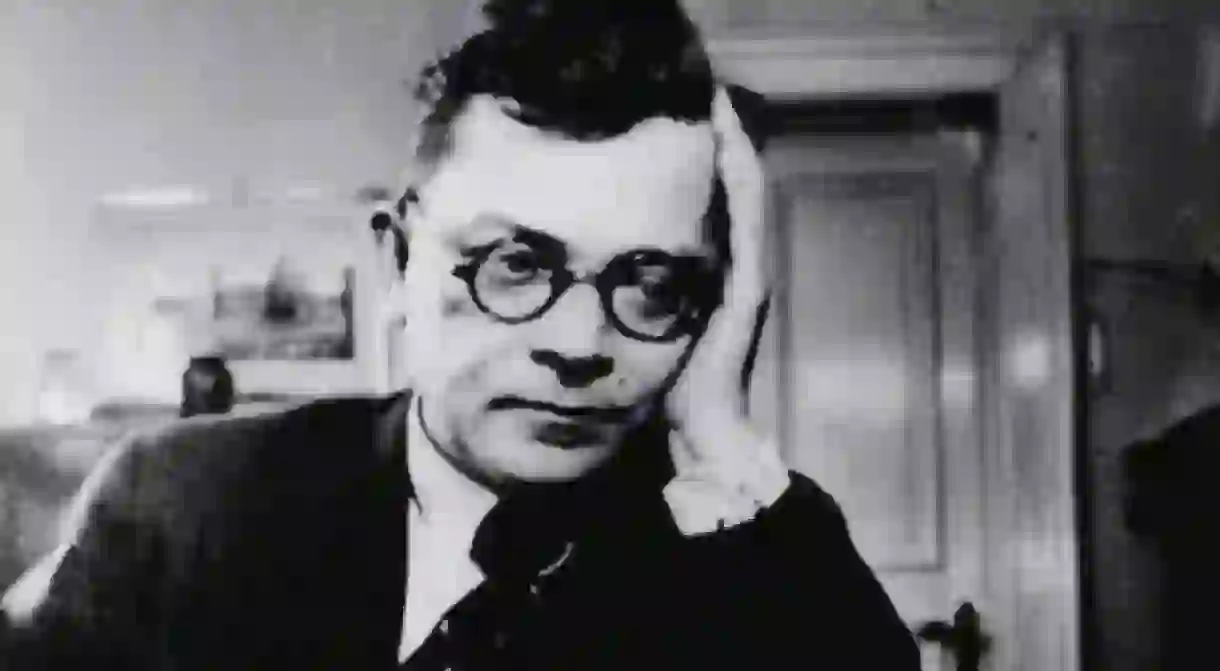

For Bone, and perhaps for Hamilton, Earl’s Court is a heavy place, a pit with its own gravity from which any escape is difficult. Though Hamilton never lived there for very long, it was in Earl’s Court that he was struck by a car in 1932 – in the exact spot from which, writing Hangover Square in 1942, he would have George Harvey Bone stand and stare at the illuminated windows of Netta Longdon’s rooms. The accident left Hamilton severely disfigured, and precipitated his fall into the sort of serious alcoholism that he would depict in Hangover Square, where Bone’s resolution not to drink results in having ‘only’ a half-dozen beers at lunch. In his introduction to Hangover Square, J.B. Priestley wrote of Hamilton that he ‘needed whiskey like a car needed petrol’.

Hamilton had become a success early: his first novel, Monday Morning, was published when he was 21, and at 25 his play Rope (later made into a film by Alfred Hitchcock) made him wealthy. Following the car accident, Hamilton’s work became increasingly misanthropic – a trend hinted at in the good-hearted Bone’s continual failures in his struggles for dignity with his narcissistic ‘friends’, but one that reached its peak in the Gorse trilogy of books, whose critical lambasting prevented Hamilton from receiving the kind of mainstream recognition that his work deserves. Though various attempts have been made to revive his image in the popular consciousness, and even to rehabilitate the Gorse trilogy, he remains hugely underrated: for few have managed to paint a picture of the low and dark areas of London, and the people that inhabited them in the 1930s and 40s, as effectively or viscerally as Patrick Hamilton does in Hangover Square.