A Portobello Life: An Interview With Novelist And Market Trader Laura Del-Rivo

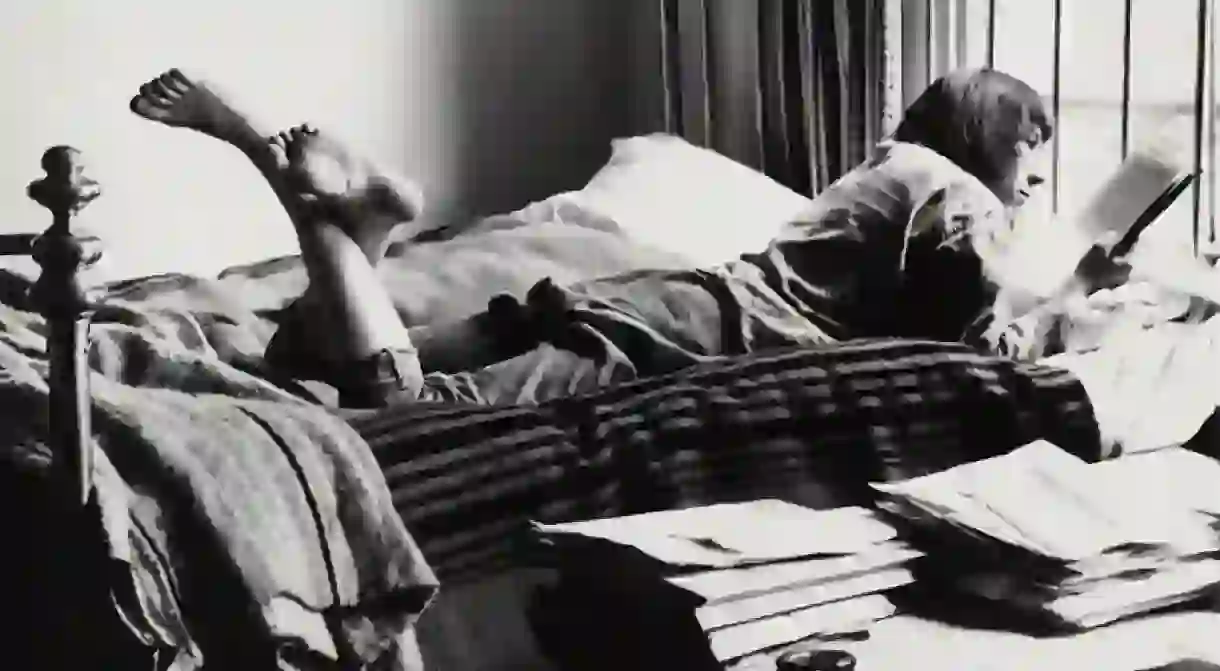

Laura Del-Rivo rose to prominence in the 1960s with the publication of her debut work, The Furnished Room, which was adapted for the cinema by Michael Winner, before abandoning fiction writing for a career as a trader in London’s Portobello Market. She has now returned with a collection of short fiction entitled Where is My Mask of an Honest Man? which both harkens back to her earlier work and reveals a new side of the London writer.

Q: How would you describe Where is My Mask of an Honest Man? Where does it fit in with the rest of your novels and stories?

A: I wrote the stories over the last eight or nine years. I am 79 and live alone. What I write is therefore limited: I am too old to write sex and have no experience of domestic.

Q: Your choice of Notting Hill as a location is something you have returned to many times during your career. What draws you to this location and how does it inform your work?

A: In the mid-1950s my friend Colin Wilson lived in Chepstow Villas, in what was then a bare but beautiful house of writers and painters. When the press hounded Colin out, I took over his room. I have remained in the area. It is easy-going and has a market.

Q: Your work engages in a diverse range of styles — there is a balance of realism and surrealism throughout Where is My Mask of an Honest Man? Which are you more comfortable with and why do you employ these various styles in your work?

A: My ideas and descriptions elongate or distort into a surreal form. It is a visual faculty.

Q: How has your work progressed since the publication of The Furnished Room in the 1960s and how has the publishing industry changed over that period?

A: The Furnished Room was actually written in the 1950s. My work now is less influenced. The famous publishers of the 1950s were independent houses, typically run by an individual, a family, or a partnership. The name over the door was generally the name of the man behind the desk. If a publisher rejected your masterpiece, you got a helpful letter with advice, not a duplicated chit. Publishing was respected as ‘an occupation for gentlemen’. Big publishers now seem ultimately owned by world conglomerates who have bought up the means of productions of everything from building contracts to detergents. I am not complaining; only noting the circumstances. There remain small publishers like Holland Park Press. I was lucky in the timing of The Furnished Room as Hutchinson had just started their New Authors imprint which specifically wanted unpublished writers. The door was open; I got in.

Q: There seems to be a commentary on The Furnished Room – and on the film of it by Michael Winner – within Where is My Mask of an Honest Man?; what is your perspective on The Furnished Room now and on your early success with it?

A: The start of ‘Dark Angel’ (the book’s opening story) deliberately reprises the start of The Furnished Room with the problem of a man trapped in an interior. If the room is given, such as a lodger’s room or a room in a hotel, there is not much the tenant can do to surmount what I have called boredom or dismay or horror.

Q: The Furnished Room was an autobiographical work. Do you consider Where is My Mask of an Honest Man? to be in a similar vein?

A: Krissman’s misanthropy is mine; so is Joan Byker’s domesticity and her interest in wild flowers. Harry Brightling’s experience of antique dealing as morally dangerous was also mine when I dealt in second-hand stuff. Objects I saw, such as human and dog feet under the bus shelter, and the ogre-fisted bare branches of London plane trees, got written in.

Q: As a confirmed London writer – someone who has lived in the city and given it voice in literature – what are your favourite London novels and writers?

A: I don’t require an author’s address before reading their book. The writers active now whose work I most admire and enjoy include Alan Hollinghurst, D.C.B. Pierre, Scarlett Thomas, Hilary Mantel, David Mitchell. A specifically London book would be Capital, by Maureen Duffy, for its time-travel concept.

Q: Tell us about you experience of balancing your career as a market trader in Portobello Market and being a writer? Does working in such a thriving spot inform your writing?

A: Being naïve, I would consider it wrong to misuse my gift of writing. Market trading also is autonomous, the buying part is creative and I like being outdoors. The two jobs balance well. I am hindered on the market by my prosopagnosia (difficulty in recognising faces).

Q: You take London as the subject and background to much of your published work, how does the city inspire your writing and how has it changed from the Bohemian city you depicted in the 1960s?

A: Early 1950s, not 1960s. As a leftover from the war, things were institutionally inconvenient. The episode in ‘Dark Angel’, in which Kuhlman tries to buy a bar of soap on a Sunday, and finally steals one from a public lavatory, is true. London then was less crowded, had less traffic, had bomb sites always within view, and was white. My first job in 1951 was in Charing Cross Road. Apart from Ras Prince Monolulu, (the horse-racing tipster famed for his famous catchphrase, ‘I gotta horse’) the few Africans passing by had tribal cuts on their faces. Shop and office workers spent their lunch hours in the cafeterias of Lyons and the A.B.C. Expectations were insular. Only Soho sold continental foods and coffee.

By Thomas Storey