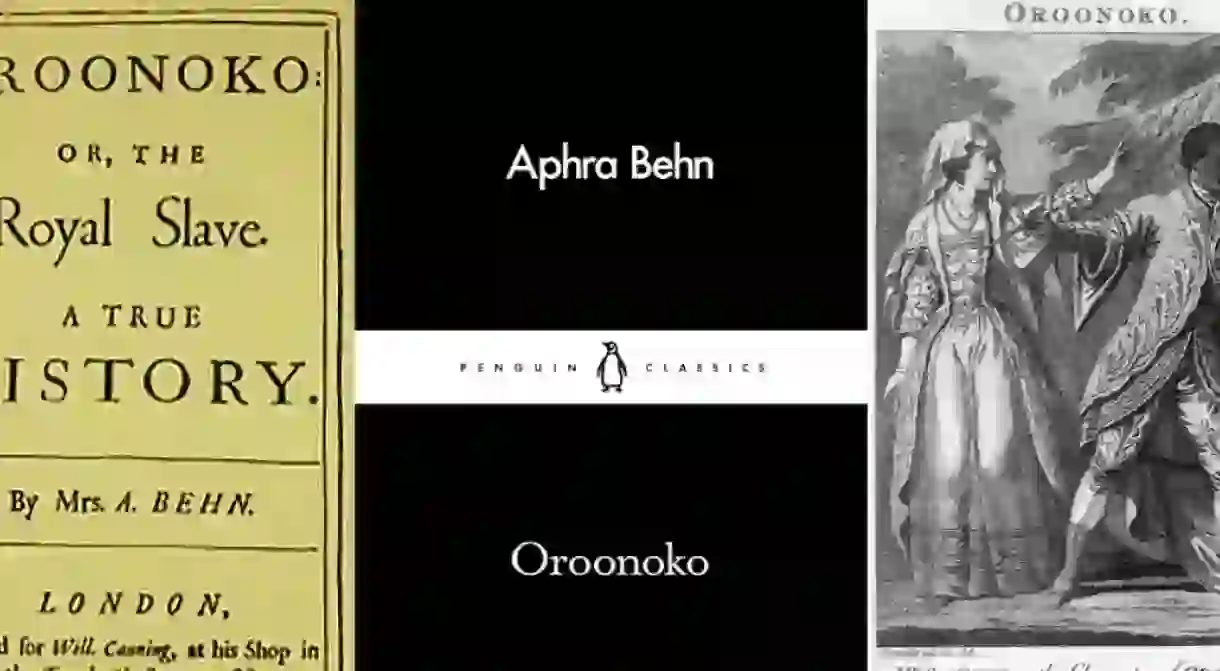

Oroonoko By Aphra Behn, The First Novel Ever Written In English

The fact that it was published in 1688 – and is thus a strong contender for the honour of being the first novel published in English – is only one of the many delightful tidbits that surround Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko. It also happens to include a fairly strong case against slavery, and is the work of the first professional woman writer.

Ever since Ian Watt’s seminal study The Rise of the Novel came out in 1957, the bulk of relevant opinions have held Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) as the first novel ever published in English – a choice made easy by the work’s acclaim, and its constant presence in the backwaters of popular culture. While, of course, the question of firsts revolves entirely upon one’s definition of the novel (a definition that varies more than you’d think), the case for Oroonoko, published some 30 years earlier, is surprisingly strong, and often overlooked. While its length (29,149 words – for roughly 112 pages in my edition – compared to Crusoe’s 99,200), puts it dangerously close to the novella, the other prerequisites are all there: not only does it contain a realist plot (back then allegories, romances, and utopias dominated the prose scene), but said plot is both linear and biographical. In other words, it’s everything you’d come to expect from realist fiction.

The titular character is an African prince who falls in love and marries the daughter of a great general, Imoinda. His grandfather the king, however, turns out to have fallen for her as well, and gives Imoinda the ‘sacred veil’, making her one of his wives (and confining her to his personal harem). A secret affair between her and Oroonoko is soon discovered, leading the king to sell Imoinda into slavery, while convincing his grandson he had her killed. At this point, you wouldn’t be faulted for thinking there was more than enough drama for any 100 pages to handle. But remember Aphra Behn is a dramatist by trade, and changed form most likely because the evolving theatre landscape led to a drop in the demand for new plays. Her novel is thus infused with all the action typical of a fast-paced tragedy – and devoid of existential introspection (prose ain’t quite there yet).

So what happens next, you ask? Well, some time later, Oroonoko finds himself betrayed into slavery himself by an English captain, and sent to Surinam to work on a plantation. It is there that he meets our narrator – a young lady, newcomer to colonial upper classes – and reunites miraculously with Imoinda, who just so happens to be held by the same owner. Though the two are held in considerably better conditions than their fellow slaves (Oroonoko is beloved by nearly all the colonists), they both tire of their captivity, and are pushed to action by Imoinda’s pregnancy. A revolt is stirred by the prince, who then delivers the work’s most famous lines:

“And why, said he, my dear friends and fellow-sufferers, should we be slave to an unknown people? Have they vanquished us nobly in fight? Have they won us in honourable battle? And are we by the chance of war become their slaves? This would anger a noble heart, this would not animate a soldier’s soul. No, but we are bought and sold like apes or monkeys, to be the sport of women, fools and cowards, and the support of rogues, runagades that have abandoned their own countries for raping, murders, theft and villainies.”

The rebels are nonetheless defeated, after the colony’s deputy governor, Byam, promises amnesty to surrendering slaves. Once captured, Oroonoko is thus whipped and humiliated by his former allies. The lovers then escape into the wilderness, where Imoinda willingly dies at her husband’s hands to avoid a worse fate from Byam. Oroonoko is eventually found and murdered, gruesomely, by his captors, but not before ensuring those present were reminded he was a tough man: he smoked a pipe, noiselessly, while his enemies dismembered him.

***

It’s always worth reiterating just how remarkable a person Aphra Behn was. Still unconvinced? Just read Virginia Woolf’s take on the matter, from A Room of One’s Own (a requisite quote for any such article): “All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.”

If her talent is undeniable, one should also not overstate the courage it took Behn to pursue her career. While she wasn’t the only woman writing at the time, all the others were aristocrats quite unwilling to condescend to being paid for their efforts (until the Victorian era, selling your intellectual work was seen as something akin to selling, well, your body). Not only did she do so, but she survived thanks to it, and was widely known as a prolific, bawdy, and witty playwright. None of those things were easy to accomplish in the 17th century (remember Mary Wollstonecraft wouldn’t be around until a century later!).

All this contributes to making Oroonoko a uniquely radical work–it isn’t just a novel, it is a powerful testament against the horrors of slavery; it is an anti-Dutch political tirade (published just before the Glorious Revolution); it was the livelihood of the first professional woman writer in Britain; and it is, finally, a subtle case against the powerlessness of women in society.

OROONOKO

or, the Royal Slave

by Aphra Behn

Penguin Classics, 128pp, £2, March 2016