Critical, Commercial and Cutting Edge: Faber & Faber’s Publishing Revolution

Founded under the name Faber & Faber in 1929, Faber is an independent publishing house that has become a British legend. A company not afraid to take risks, Faber’s history has seen it publish works by T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Sylvia Plath, Seamus Heaney, Philip Larkin and many more. Christopher Viner unveils the story of this English icon, analysing the factors of its ongoing success.

In March 2013, Emily Berry – at the time a relatively unheard of poet who had made a stir on the little magazine scene – released her first collection of poems, Dear Boy, to critical acclaim. The Guardian praised Berry for approaching poetry as, ‘a flexible, permissive, dynamic ally.’

A few months prior, in the Autumn of 2012, her friend Sam Riviere – co-editor of the anthology Stop Sharpening Your Knives – released his first collection, 81 Austerities, which began as a blog of poems renouncing the Tory cuts (or using the austerity measures as a platform to explore other contemporary territory). The book created a stir with its calculated and exceptionally crafted poems about living in a world of social networking and videos on mobile phones, prompting the Independent to hail Riviere’s collection as, ‘a sexy book’.

Both books broke new ground in terms of form, both were admired for their accessibility and both were published by Faber: a commercial publishing company who have managed to retain credibility, even amongst the most esoteric and hard-line literary sects. But how have Faber managed this perplexing balancing act of commerciality vs. credibility? To answer this, we need only look at its list of household names, beginning with a young, ambitious London banker, who joined the company as a director when it was originally established in 1925. His name was T. S. Eliot and he went on to become one of the most important publishers of the 20th century – his poems weren’t bad either.

In 1925, Geoffrey Faber decidedly broadened his publisher’s scope by migrating from the medicinal publishing industry and went on to his first general press: Faber and Gwyer. They got off to a good start by publishing T. S. Eliot’s Poems 1909-25 in the Autumn of the company’s founding year. By 1929, they changed their name to the less STM sounding Faber & Faber. Why this was, there are many rumours and ‘insider jokes’ circled in texts and books on the company, but nobody really knows as there was no second ‘Faber’ (pre-empting postmodernism perhaps?)

Eliot and Geoffrey Faber proceeded to discover and publish the voices of James Joyce, Ezra Pound and Samuel Beckett, sculpting their own names in the history books as the untouchable pillars in an increasingly intricate and prolific landscape of modernism.

By the 1950s, the 13 inhabitants of the (now historic) company base at 24 Russell Square had become in excess of over 100. One major factor in their growth and survival during this period was their reluctance to do what most small press publishers could hardly help: sell their most commercial titles to the leaders on the market, Penguin and Pan. For this reason it was considered hipper to carry a Faber paperback in your zipper – the series of which had a no-nonsense title of ‘Faber Paper Covered Editions’ – than it was to carry a Penguin.

Faber had dodged the unforgivable description of ‘sell-outs’ whilst their name became more widely syndicated. By the time they boldly strode into the swinging 60s, they became not only trendier, but crucial to the literary map of today, with a list of household names that cited Sylvia Plath, Philip Larkin, Thomas Gunn, Robert Lowell and John Berryman. If Faber’s paperbacks were a little more expensive than Penguins and Pans, a peek at their list of authors gave an indication as to why.

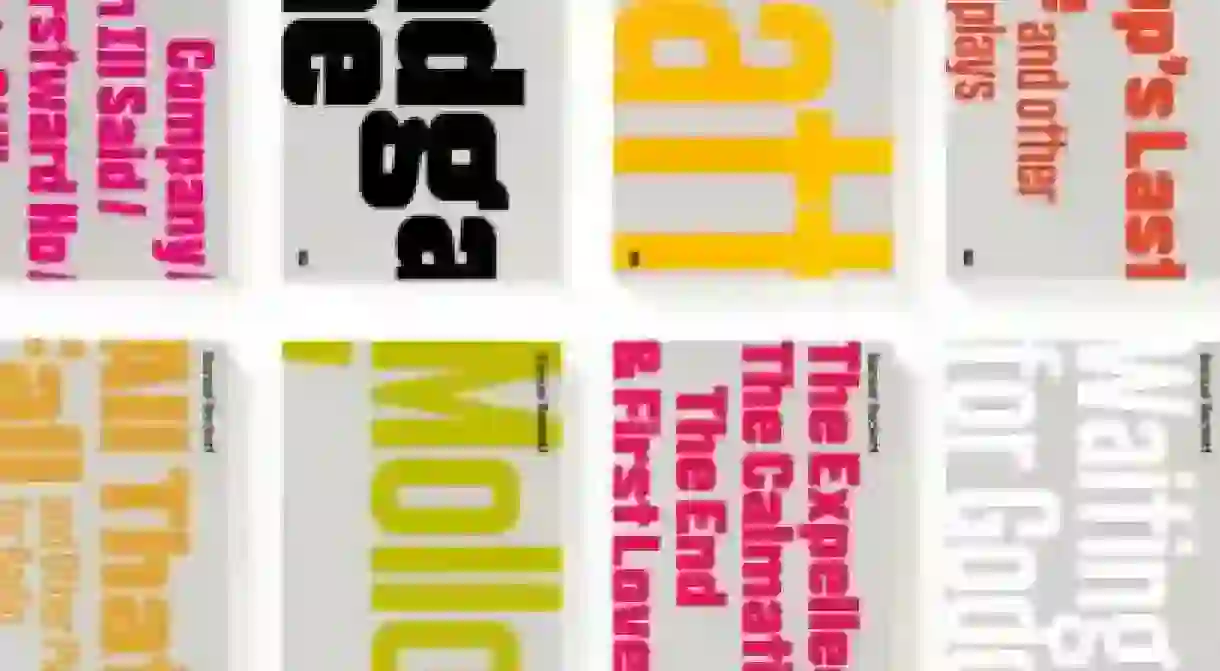

The 1970s brought Seamus Heaney to that untouchable scroll of authors – a man of talents too countless to list, one of which was to escape the umbrella under which every other author of the 70s and 80s seemed to be hiding: that of the ‘postmodernist‘. In the same decade the company moved from their original home at 24 Russell Square – now a place of national history – to Queen’s Square. Throughout the 1980s, they became known for their expressive and valiant cover designs, and by the early 1990s they released the swish single colour jackets – a design that came to symbolise the bold, sophisticated and accessible nature of the publishers.

The key to Geoffrey Faber‘s success appears to be his acceptance of what was at the time considered to be risky literature; texts characterised by their obscurity and ability to break down the traditional plot structures and forms. Faber (the man) was a poet in his own right, and this no doubt helped in his recognition of fresh, exciting and original poetry. It was by a means of the founder’s empathy with writers who were otherwise considered too unsalable or marginal that gave the company its credibility, and, eventually (when the literary world caught up to what Geoffrey Faber and Eliot had discovered) its prosperity too.

It is an ideology that happily continues to line the fabric of the company’s business model, and this is shown in the original writers and poets it publishes today – Riviere and Berry being two of its most recent voices.

The way in which Faber thinks about publishing – seeking out fresh voices and taking courageous risks in the publishing of them, rather than printing works that sit too safely within tired literary lines – is a mode of thought that would surely re-energise some of the more sterile business models of the West. In a consumer culture that often gives more importance to profit margins than to originality and quality, there is a lot to be learnt here from Faber and its ideologies. With a little risk and valour, it is possible to be both commercial and credible, whilst also filling the world with everlasting works of art in the process.

By Christopher Viner