Previously Unseen Sylvia Plath Letters Hint at Domestic Violence, Ted Hughes Estate Denies...

…and the “most tragic literary love story of our time” proves itself tragic enough to be never-ending.

In a series of letters to her therapist Dr Ruth Barnhouse, Sylvia Plath accused her husband Ted Hughes of beating her a few days prior to her miscarriage in 1961, as well as of telling her he wanted her dead. The correspondence was only recently unearthed after an antiquarian bookseller put it up for sale for US$875,000 (UK£695,000); it had formed part of an archive compiled by feminist scholar Harriet Rosenstein for an unfinished biography.

The Ted Hughes estate, on behalf of his widow Carol Hughes, responded by saying that the allegations “are as absurd as they are shocking to anyone who knew Ted well.”

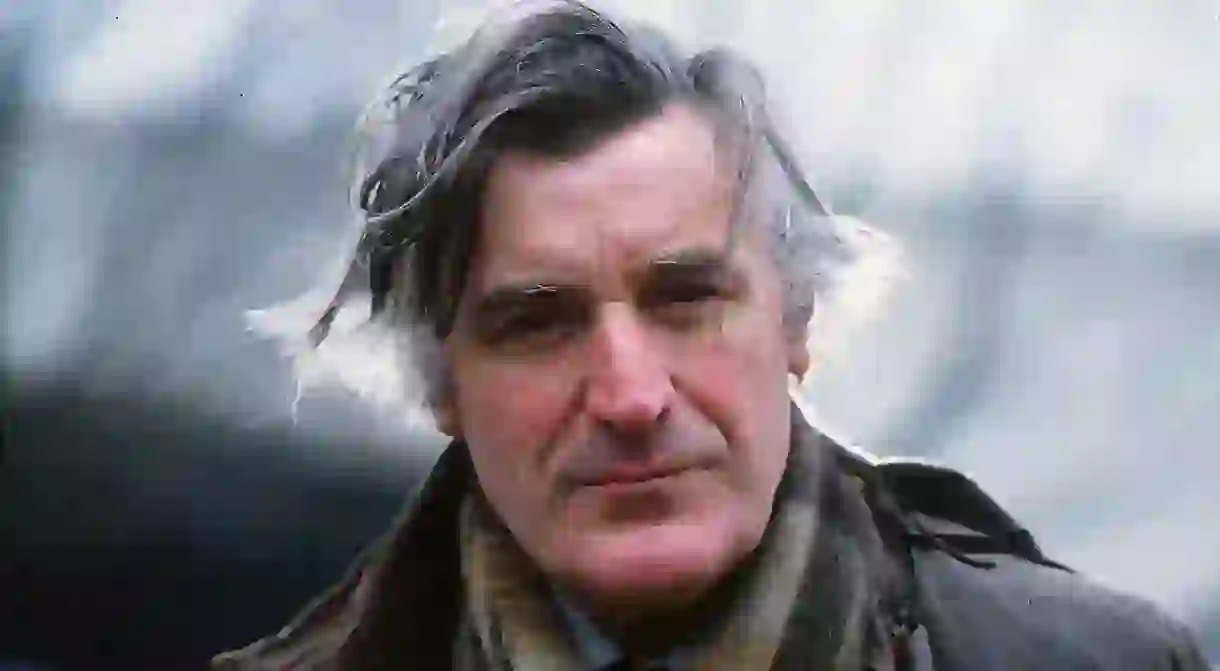

Popular interest in the marriage has been an ongoing feature of the literary world for more than half a century, helped both by the relationship’s tragic nature, and the remarkable creativity it spawned within the two poets. Boston-born Sylvia Plath met Englishman Ted Hughes at Cambridge University in 1956, and the two were married some four months later. The first wrote her most famous works within the last two years of their disintegrating marriage: the semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar in 1961, and the poems in the collection Ariel a year later. She killed herself in 1963, survived by their two children. Hughes, meanwhile, wrote a number of works related in one way or another to his wife and her suicide—the prose poem Gaudete, the collection Crow, and the most recent Birthday Letters.

These new revelations won’t of course do a thing to change the views of any side of the Ted Hughes-Sylvia Plath tussle. Not only can fans of the former be relied upon to argue that allegations like these detract in no way from his literary achievement, but I doubt they’ll be swayed by another example of his extreme ‘manliness’. By all contemporary accounts he was the most sexually successful bard since Byron (or Robert Graves, for a less adventurous comparison), with all the potential sleaziness that entails. Mark Ford, in a recent review of Jonathan Bate’s Unauthorised Life, made the point that of Hughes’s countless well-documented affairs, the only fling likely to hurt his reputation was the last: one with “a property developer based in South London […] who apparently got him to play golf.” It always catches up with you in the end, doesn’t it?

Likewise, for those in the other corner these letters simply offer the latest examples of abuse. Ted Hughes has been a figure of hate since the 1970s, haunted by the fact that both his first wife and the woman he’d cheated on her with, Assia Wevill, committed suicide, and within six years of each other. Whether or not the new(ish) allegations are true—given Sylvia Plath’s occasional extreme mental state—shouldn’t really matter; whatever you make of his influence on Plath’s psychological health (and whether his increasing annoyance at it is culpable), it’s fairly obvious he wasn’t exactly a positive influence. The fact that he burned his wife’s last journal and final correspondence after her death to “protect their children” doesn’t really help his case, either.