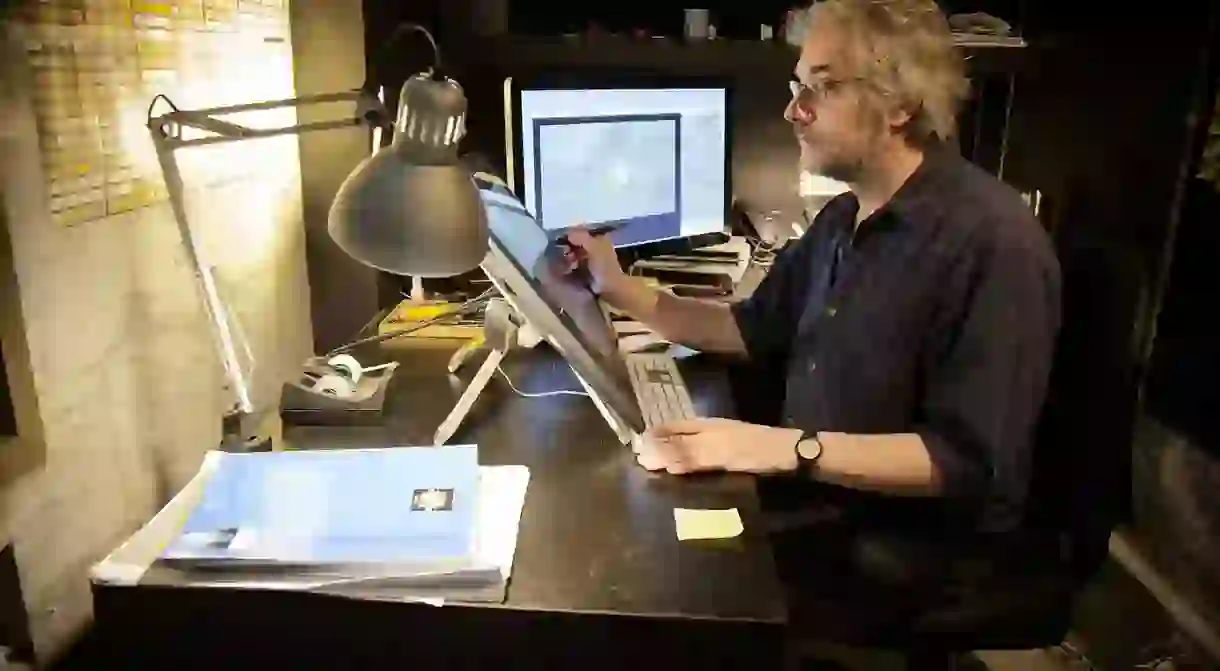

Meet the Dutchman Who Made a Studio Ghibli Film in a North London Shed

The Red Turtle, a sumptuous animation that was nominated for an Oscar after premiering at Cannes last year, is about to get a UK release. We spoke to the director, Michaël Dudok de Wit – who as the name suggests, isn’t Japanese – about how a Dutch-born filmmaker working in London came to work for Studio Ghibli.

Culture Trip: The Red Turtle is an unusual film with an incredible story behind it. Can you tell us about how it all came together?

Michaël Dudok de Wit: I’m so excited about it and working with the producers. Especially the Japanese ones. To my great relief, it’s been well-received. It’s not a blockbuster, but the press and audiences have liked it.

It came about because Studio Ghibli wrote to me. They’ve obviously made films for decades and that have character rather than just doing ‘entertainment movies’. They asked if it was something I would be interested in, working with co-producers in France and it was just those couple of sentences. I did wonder if I should go to Japan and do it in that style or if they had a story they wanted me to translate, but they wanted it made in the West – with my story and my visual style. It didn’t have to look like a typical Studio Ghibli film.

CT: Were you happy to have that free reign and creative control?

MDW: I was totally happy! That’s how it works with my short films. This is my story, and I just asked that they trust me. With a feature film, it’s never a pure expression of one person, as it’s a collaborative process. I knew I wanted to be the writer, but I needed their feedback. They are experienced in things like narrative flow and so on, but also I wanted to know how they read the symbols and metaphors in there and how they work in their culture. We had junior animators who came to work on it, and that fresh look was something I was keen to work at with them as well.

CT: So what are some of your personal influences, either from the Studio itself, or beyond?

MDW: The first film I saw from Studio Ghibli was Castle in the Sky in the early nineties. I had never heard of them, and wasn’t aware that there was one studio that stood out from the crowd like that. I asked a colleague about it at a film festival, and I wanted to know if it was just me or if it was one of the most incredible things I had seen. He told me about them, and I knew I had to find more.

[My Neighbour] Totoro (1988) is amazing and also Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Totoro is clearly a classic, a huge hit in Japan and everyone interested in animation knows about it. Grave of the Fireflies, by Isao Takahata, is very emotional, and it still makes me cry. Takahata also made another film, My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999),which is so pure and quiet. It reminded me of Haiku poetry where nothing is said and yet you know exactly what is meant. It’s something you shouldn’t do, but he did.

CT: It’s something that you did yourself with The Red Turtle though. How hard is it to convey emotion with that lack of dialogue?

MDW: That’s a great question, because what I wanted was purity and simplicity. I was worried that there would be moments that were too quiet and the audience would disconnect, especially as most people are used to non-stop dialogue. There aren’t any bright colours or dynamic chase sequences.

We had years to work on this film. We refined it, and spoke about the simplicity. The landscape artists were aiming for that too, so we had rich forests but they were all made out of bamboo and the vertical lines fit the idea of purity.

Another one of my favourite films, given that I was not a film buff at all as a child, is Seven Samurai (1954) by Akira Kurosawa. I didn’t have high hopes, but when I was a student I fell in love with cinema. I became acquainted with the culture and was sucked into the story. The choices he made about nature and how to depict that, made me realise how far cinema can go. What a delight.

CT: Audiences and critics around the world have fallen in love with your film, but what has been the reaction in Japan?

MDW: We opened in late August, and I did lots of interviews. The press was so positive and the translator was gasping at the reaction. My main producer, Toshio Suzuki, however warned me that Japanese audiences like Japanese films. It’s obvious, and much like Americans in that sense. Perhaps Europeans are a bit more nuanced in cinema.

He thought it might have a chance because it had a sensibility that might do well, but to be honest the numbers were not great. I was sad about that because I wanted Japan to love it. It wasn’t a disaster, but The Red Turtle came out at the same time as an impossibly popular film, Your Name (2016). That animation spoke more to a younger generation and talked directly to them. It’s probably a factor as to why we didn’t do that well.

I asked Toshio who went to see our film, and he said film buffs and an older audiences.

CT: Finally, you mentioned some of the live-action films that have influenced you, is that something you want to do next?

MDW: No. Live-action is simply not my talent. I don’t see it. I’m someone who draws and I’m an illustrator at heart. My films are about realistic human behaviour, but I still recognise the beauty about having a line around a character. I feel that graphic beauty.

The Red Turtle is out now.