David Jones: Artist, Poet And Visionary

David Jones is known for his poetic World War One memoir, In Parenthesis, but there were many strands to his artistic output. A new exhibition at Pallant House Gallery urges us to consider Jones’s whole oeuvre with his various engravings, inscriptions, drawings, water-colours, and poems forming an integral whole.

The centenary of World War One has brought to the fore one of the most remarkable accounts of war service, David Jones‘ superbly poetic memoir In Parenthesis. But a new exhibition, David Jones: Vision and Memory, at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester urges us to consider David Jones’ entire oeuvre. Artist, wood-engraver, illustrator, designer of inscriptions, poet, London-born Welshman, there are many strands to David Jones’ life. He was one of the first British modernists, and was considered to be of major importance as a writer by T.S. Eliot.

He was born in south-east London to a Welsh father and a London-born mother. As his father had been discouraged from speaking Welsh as a child, David Jones did not speak the language, but it would remain a significant component in his artistic make-up. He was talented early on: the exhibition includes a drawing of a lion produced when he was just seven. He studied at Camberwell College of Arts, where his work was described as ‘leaving everything out except the magic.’ He enlisted at the beginning of World War One, serving from 1915 to 1918, and he served longer on the Western Front than any other major war poet in the UK. This shaped his whole life.

After the war, he returned to study at Camberwell. It was during this period that David Jones became a Roman Catholic; his religion would become increasingly important in his art. At this time he came under the influence of Eric Gill, a religious artist, and eventually joined Gill’s artistic community, the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic in Ditching. When Gill moved to Wales, Jones continued to visit him and would have a long relationship with Gill’s daughter, Petra.

His initial work was in illustration, engraving and watercolour landscapes. Although his work changed style at various times, these mediums would remain key. His life was punctuated by a series of nervous breakdowns, the first major one in 1933 around the time he was working on In Parenthesis, and he suffered another in 1948. Wandering around Pallant House Gallery’s chronologically arranged exhibition, it is difficult not to come to the conclusion that after each of these episodes Jones’ work changed style and direction.

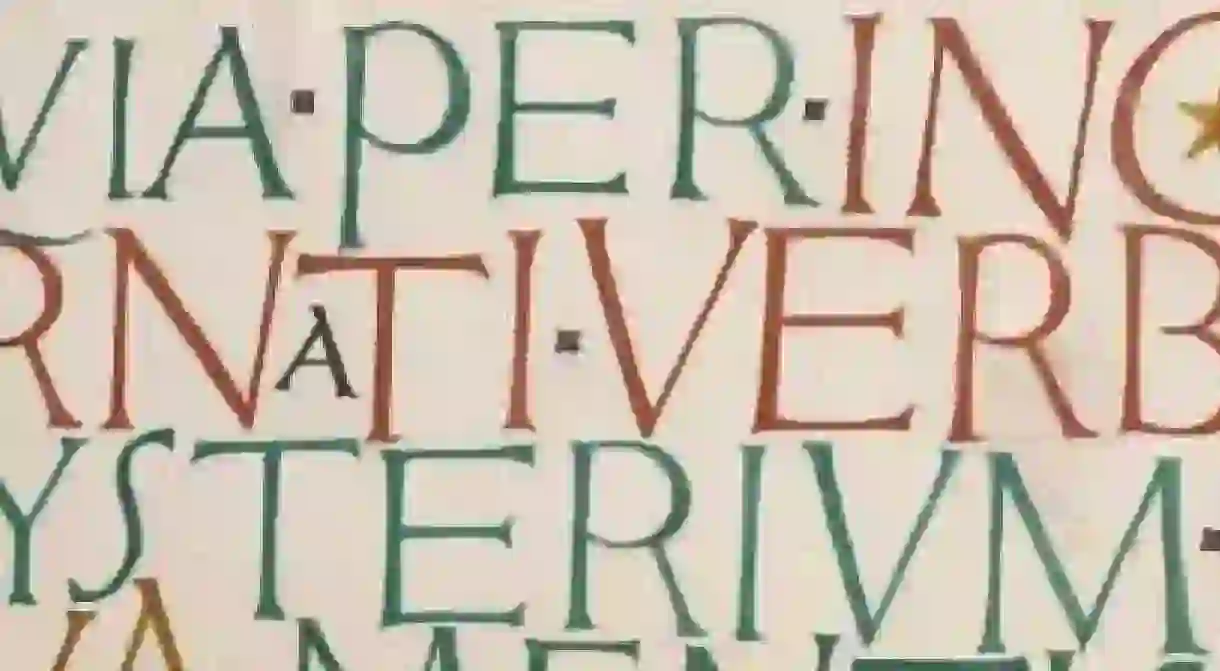

With a father who was a printer’s manager, it is not surprising that Jones had an interest in type and lettering. The style of his lettering reveals some of the influence of Eric Gill, as do some of Jones’s drypoints and engravings from the 1920s and 1930s. Engravings on wood and on copper thread their way through the whole of Jones’s career as a medium to which he constantly returned. His wood engravings for the Book of Jonah combine Eric Gill-like clarity with other modernist influences.

In his watercolours from the 1920s we can see nods to Picasso, Braque and Matisse, but woven into his own distinct style. His portraits mix firm lines with the abstract. ‘Human Being,’ of 1931, is one of only two self-portraits he painted, and his portrait of Eric Gill from 1930 is not at all Gill-like in its execution, with its supple lines and mysterious watchful feel. His landscapes show hints of Cézanne, and there is often a sense of narrative and of mysticism in them. In the 1930s, magic casements became a theme, like windows onto lyrical seascapes. David Jones was clearly very independent of others working around him, although you can see clear influences of them absorbed into a highly developed sense of his own magic.

After the Second World War (and his second major breakdown), religious and Arthurian themes come to the fore. A series of chalices can be seen as evoking religious feeling but also forming links to the holy grail. Arthurian themes are more explicitly present in works like ‘Guenever’ (1938-40). In these later works, the sense of surface detail is profuse, often incorporating complex and subtle iconography. Some are disturbing and brilliant such as ‘Aphrodite in Aulis’ (1940-41) with its undertone of sexual aggression. Or ‘Vexilla Regis’ (1947-48) with the detailed Christian iconography woven into the image of trees.

Another later work is his poem ‘Anathemata,’ which takes place in the context of mass, and which T.S. Eliot regarded so highly. With a polymath like David Jones, it is easy for one branch of his art to dominate the rest, but this show from Pallant House Gallery (and the excellent book produced to accompany the exhibition) helps us to recognize his artistic output as a balanced whole. A resolutely independent soul, David Jones’ artistic development took a very different direction to that of the modernists with whom his early work is linked, and it remains all the more fascinating for it.

The exhibition David Jones: Vision and Memory is at Pallant House Gallery until 21 February 2016, and there is a complementary exhibition, The Animals of David Jones, at Ditchling Museum linked to Jones’s period with Eric Gill’s guild in Ditchling. Jones’ poem ‘In Parenthesis’ is being turned into an opera by Ian Bell, which will be premiered by the Welsh National Opera in Cardiff on 13 May 2016.