An Introduction To Akala, 'The Black Shakespeare,' In 8 Songs

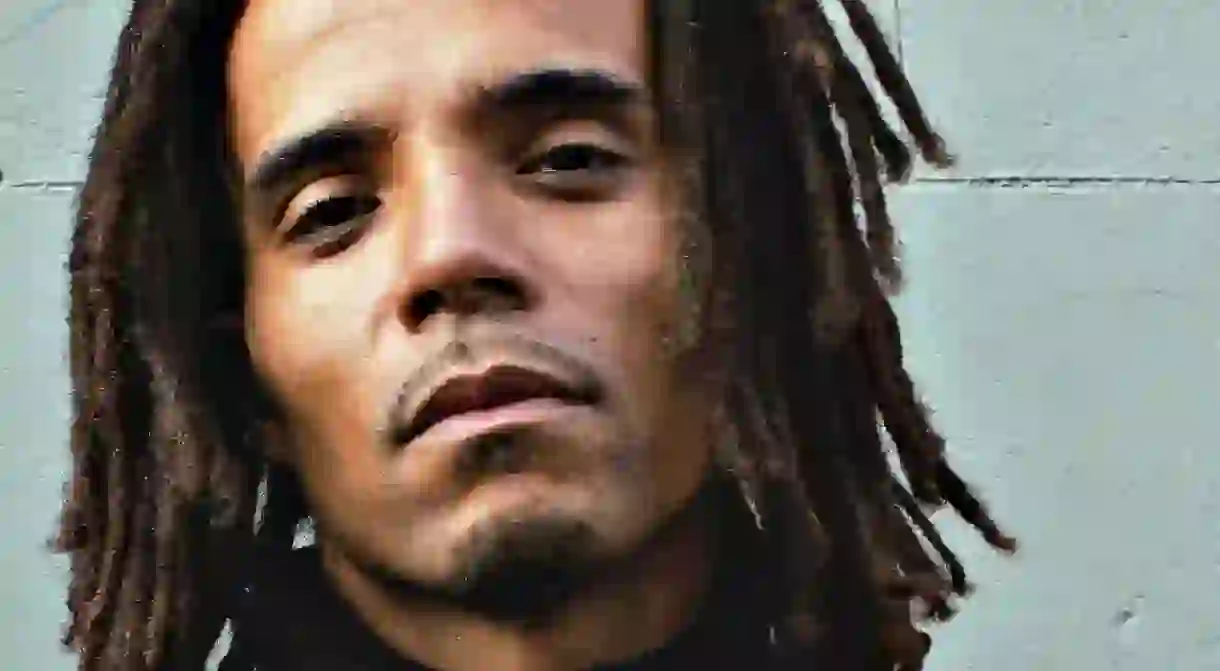

Kingslee James Daley, better known by his stage name Akala (a Buddhist term meaning immovable), is a London-based rapper, poet, and academic. His sharp intelligence and articulate opinions have elevated his into a highly credible and influential political voice. The younger brother of rapper and vocalist Ms. Dynamite, Akala’s brand of hip hop is a conscious one, tackling issues of society, race, global inequalities, and the lingering hangover of imperialism in the western world. Here’s an introduction to this quick-spitting wordsmith in 8 songs.

“Shakespeare” (2006)

Personally inspired by England’s national poet since childhood, Akala is passionate about both the linguistic and the socio-cultural parallels that exist between the works of Shakespeare and that of modern day hip-hop artists. In 2009, he set up the Hip Hop Shakespeare Company, a musical theatre company of which Sir Ian McKellan is a patron, to promote and put into practice these beliefs. It encourages young people to consider Shakespeare as approachable, rather than dated and elitist, while at the same time promoting hip hop as an intelligent and poetic medium of expression. “Shakespeare” is off the rapper’s debut album, It’s Not A Rumour, and acts as a hip-hop homage to the Bard of Avon.

“Comedy, Tragedy, History” (2007)

Released one year after “Shakespeare,” this song seems a natural progression in our list. The rap in “Comedy, Tragedy, History” contains the titles of 27 Shakespeare plays, and is peppered with allusions to their contents. Arguably, one of the most significant lines in the song opens the fourth verse:

Akala, Akala, wherefore art thou?

I’m the black Shakespeare and

The secret’s out now.

“Wherefore art thou” is, of course, a reference to the famous line in Romeo and Juliet, and sets the rapper up to introduce himself with his new title, by which he is now widely recognised: the black Shakespeare.

“Peace” (2010)

A different style than the rest of his fired-up songs, “Peace” sounds much more like a contemplative poem, spoken over dreamy music, than a rap. The tranquil piano chord progressions are the only accompaniment to the MC’s voice as he outlines all the threats to peace that currently exist. In classic Akala style, he sardonically alludes to the sense of superiority felt by “Great, Great, Great, Really Great” Britain. He muses that these are threats that will happen “one more time” before peace is achieved, suggesting how corrupt the world is and how many obstacles must still be overcome.

“Malcolm Said It” (2013)

This song acts as an ode to great black revolutionary figures throughout history, its chorus reading:

Malcolm said it

Martin said it

Marley said it

Ali said it

Garvey said it

Lumumba said it

I weren’t there but I’m sure Dessalines said it

Akala then explains what they all have in common: “If you ain’t found nothing to die for, you’ve never lived.” This is reminiscent of a sermon made by Martin Luther King Jr. (the “Martin” referenced in the second line), in which he asserts that “if you have never found something so dear and precious to you that you will die for it, then you aren’t fit to live.” Essentially, all of these great leaders were fighting, and willing to die for, the pursuit of equality.

“Welcome to Dystopia” (2010)

The song begins with the sound of distortion and feedback, and Akala’s voice, manipulated and robotic, repeating “Conform. Conform. Conform.” He picks out elements of modern society, including IVF conception and a growing youth culture of drug abuse and violent video games, to suggest that the world we live in is a dystopian one. He laments the prevailing human condition to rule or be ruled, and how one minority has authority over the rest.

The rapper repeats the mantra in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 that “War is peace – ignorance strength – freedom is slavery,” to further suggest that dystopia and reality have become hopelessly entwined.

“Absolute Power” (2012)

The thematic inspiration of this song is the famous quotation “absolute power corrupts absolutely,” coined by Lord Acton in the 1800s. Akala plays on this historical idea, bestowing his own insight upon it:

Absolute power corrupts absolutely

But absolute powerlessness does the same

It’s not the poverty

It’s the inequality that we live with everyday that will turn us insane

Poverty, to the rapper’s mind, is not the problem; it lies instead in the disparity between those with power (read: money, white people), and those without. The angle then slants towards the injustice of institutionalised racism, shining a light on two of England’s largest musical festivals.

Go to Glastonbury any year

You will see, unlike carnival

It won’t be crawling with police

Outside of his hip-hop career, Akala has challenged the differences between the policing of Notting Hill Carnival and Glastonbury Festival. The former is heavily policed with armed officers, and the latter, he claimed in an Intelligence2 Debate in 2015, “gets free reign.” Putting forth a generalised definition, reggae, the music of Notting Hill Carnival, is “black music” and rock, the music of Glastonbury, is “white music.” This division is also reflected in the demographic of each festival’s attendees. Akala takes their differences as a reflection of the enduring inequality of experiences between black and white people in England.

“The Thieves Banquet” (2013)

One of Akala’s more theatrical songs, the rap reads as a mythical story. The devil hosts a banquet gathering the greatest thieves in all the land in a competition to decide who is the most evil. In the end, the devil is left with four sets of thieves: the monarchs of empire, a cartel of bankers, the heads of religious orders, and the third-world dictators. The four then put forward individual cases explaining why they believe that they should be crowned the king of thieves. The devil finally establishes the cartel of bankers – representing money and the corruption it brings – as the greatest source of evil, because all the other groups depend on them. The song concludes with this threat from the cartel of bankers, and an allegory of modern life:

So Mr. Devil, give me the medal

Don’t be biased

If you don’t give it to me

I’ll just buy it!

“Fire In The Booth Part I” (2011)

Akala starts off by rapping about his upbringing, a child of a single-parent family, growing up surrounded by drug abuse and violence, and branded as unintelligent because of the colour of his skin. This early experience of racism leads him on to the larger problems of the racial injustice rife within Britain and the U.S., such as the troubling statistic that the overwhelming prison population is black.

He urges the need for active change with lines like, “When the world’s this fucked up, lethargy’s a crime,” echoing the sentiments of Edmund Burke, who famously said “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” It’s worth noting that “Fire In The Booth” is off Akala’s mixtape Knowledge Is Power, as this is precisely the message the rapper promotes in this song. “For me,” he said in an interview with Stereoboard, “hip hop has always been about speaking out against power — or more specifically, speaking out against injustice.”

All of these songs feature on Akala’s album, 10 Years Of Akala.