Slovakian Photographer Viera Levitt: Beauty And Brutalism

The adjective ‘brutal’ seems antithetical to our concept of beauty. The word’s negative connotations may help explain why Brutalism has been so criticised; the exposed concrete aesthetic is, admittedly, not a style that is easy to love. However, recent years have seen a reappraisal of this challenging 20th-century movement. Viera Levitt, a Slovakian-born photographer, strives to show the hidden beauty within Brutalism with a recent show in Rhode Island.

The term is Brutalism derived from the French phrase béton brut meaning ‘raw concrete’, inspired by architect Le Corbusier. It is a divisive style, and Levitt explores the converse of the negative reactions invoked by Brutalism, depicting the style as inherently heroic in her photography.

Brutalist architecture has been omnipresent throughout Levitt’s life in Slovakia and USA. Levitt, who left Slovakia to work at Rhode Island School of Design in New England, arrived in the USA with an impressive pedigree as the youngest museum director in the history of Slovakia. In her career as gallery director, she has found herself working at universities that are defined by Brutalist architecture. In 2009, she became director of the CCRI Knight Campus Art Gallery in Warwick. She was continually inspired by the bold Brutalist megastructure on campus, yet at the same time she also observed the lack of enthusiasm amongst others towards it.

Consequently, she organised We Talk about Architecture, Architecture Talks Back, an award-winning exhibition and panel discussion that actively encouraged people to engage in dialogue with Brutalism.

Three years later, Levitt was appointed gallery director at the University of Massachusetts (UMass) in Dartmouth. She relished the opportunity to work at another Brutalist designed campus, this time created by Modernist architect Paul Rudolph. In the same year, she had a solo exhibition at Hera Gallery called Beauty in the Beast: Photography of Brutalist Architecture. The subjects of her photography included the two aforementioned campuses as well as the Fall River Government Center, buildings in her native Slovakia and Boston City Hall.

The latter is an interesting case study, as Boston was at the forefront of this architectural movement in the USA during 1950-1970s. The founding of the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1957 brought together architects with a vision of restructuring the city. So Brutalism manifested itself as an integral component of this new urban project that aimed to herald a new horizon for the city.

Meanwhile in England during this period, architects Alison and Peter Smithson were leading New Brutalism. They were influential in imbuing the movement with a grand philosophy. The raw concrete buildings were meant to represent an exciting social utopian future. However, the monumental constructions were greeted ambivalently by the public.

It is this history of disdain towards Brutalism that Levitt is dedicated to counteracting. Her 2013 solo exhibition Brutally Sweet at Rhode Island gallery AS220 Project Space is emblematic of her approach. The title alludes to the supposed oxymoron between Brutalism and beauty. The architecture is a bold and muscular style that is well adapted to monumentality. Yet some would view it as being uncompromising, cold and severe.

However, Levitt’s creativity is not stunted by the sight of monochrome concrete buildings. Instead she views it as something that is full of potential: an open canvas for experimentation. Her photographs capture honey and molasses dripping down a Brutalist façade, injecting a sense of playfulness to what was previously a stern and unflinching architecture. So Brutally Sweet is able to showcase Brutalist building as something that is poignant and beautiful – something that is not immediately obvious to the casual observer.

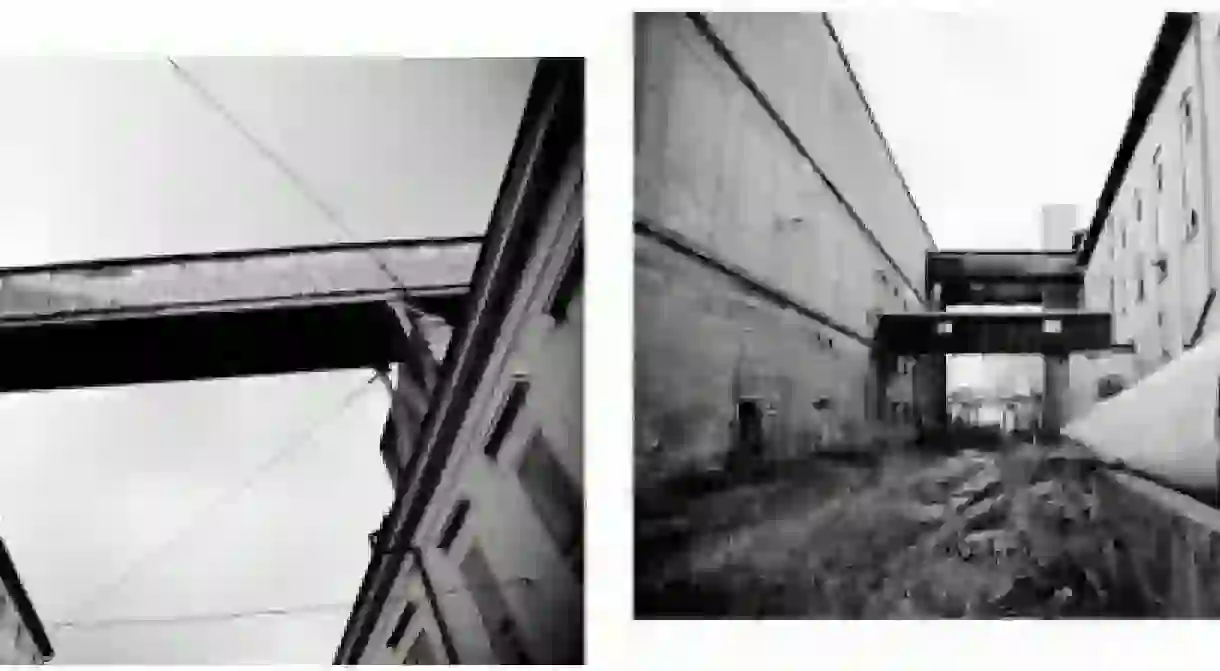

Her most recent exhibition, Old World was hosted at Hera Gallery this summer. It was a photographic exhibition that portrays the decaying urban fabric of a sugar mill in Trnava, Slovakia. Built in the 19th century, it was once an economic powerhouse in the town. However, it closed in 2004, eschewed by a new reality: rampant capitalism. Levitt is able to bring the abandoned sugar mill to life, providing it with space to breathe in her landscape photos. It is symbolic for Brutalist buildings were grand in scale as well as in aspiration with its explicit utopian impulse. Yet now the sugar mill just sits derelict, shunned by wider society.

So Levitt has noticed similarities between the Brutalist buildings in USA and Slovakia as a spirited form of architecture. Brutalism was conceived as new and daring way to build civic and governmental buildings.

However, we have reached a crucial point now whereby there is a greater urgency to the discourse on Brutalist architecture. Most of these buildings are at least 50 years old and are in desperate need of renovation. This is because they do not age well particularly in damp weather. So we have arrived at a crossroads where decisions have to be made about whether we should preserve these buildings or demolish them.

Yet Levitt’s intimate photographs are an important contribution to the debate. Her curatorial approach reveals the complex geometric forms and subtle nuances in Brutalism. It is through her lens that we are able to witness the hidden beauty within this heroic architecture.