The Most Bizarre Statue in Serbia: Vojvodina's Rocky Balboa

Have you ever heard of the Serbian town of Žitište? If so, the chances are that the unusual statue in the centre of the village first brought its name to your ears. This underdeveloped agricultural village needed a hero, so they turned to an iconic figure that everyone could identify with: Rocky Balboa.

A little bit of history

Žitište’s history dates back to the 14th century, when it was a small Hungarian settlement with the somewhat unpronounceable name of Zenthgyurgh. It was inhabited by Serbs, but hardship and disease meant it was entirely abandoned by the beginning of the 18th century. New Serbian settlers came in, and the village we know and love began to take shape. The name ‘Žitište’ wouldn’t come into use until 1947 however. Less than 3000 people live here today.

The search for a hero

And that was truly that as far as Žitište went, but a group of local youngsters decided to change that. They were led by Bojan Marceta, who came up with the idea to build a statue to a universal ideal in the centre of town. Bojan wanted something that would symbolise perseverance, hope, hard work and heart. There were plenty of options, but one name stood out: Rocky Balboa.

Despite the unconventional nature of the choice, the majority of the local community was well and truly behind the idea. Small murmurs of disapproval came from the Serbian Orthodox Church, but even this was not entirely serious. The mayor approved the idea, and the largest business in the town (Agroživ, then one of the largest chicken processing plants in Europe) pledged financial support.

The sculpting of the icon

The town needed an artist to put together this paragon of integrity, so who better than the man who carved the original? A. Thomas Schomberg was the artist responsible for the famous Rocky statue in Philadelphia, and he was soon exchanging emails with Marceta. Schomberg even offered to waive his own fee to make the statue, meaning the cost of the project would only be $1.5 million. The use of the word ‘only’ there is somewhat liberal.

Žitište didn’t have that sort of money to throw at a statue, so an alternative was found closer to home in the shape of local artist Boris Staparac. The Croatian sculptor also offered to waive his fee, meaning the building of the statue would cost an all the more reasonable €5,000 (about $6000).

The hard work began in earnest, as the entire town was infected with Rocky fever. The monument was bringing people together before it had even been erected, as the entire community rallied behind this memorial to the power of believing in yourself. The big unveiling was set for August 18, 2007, where it would act as the main event of that year’s Chicken Fest. Yes, Chicken Fest.

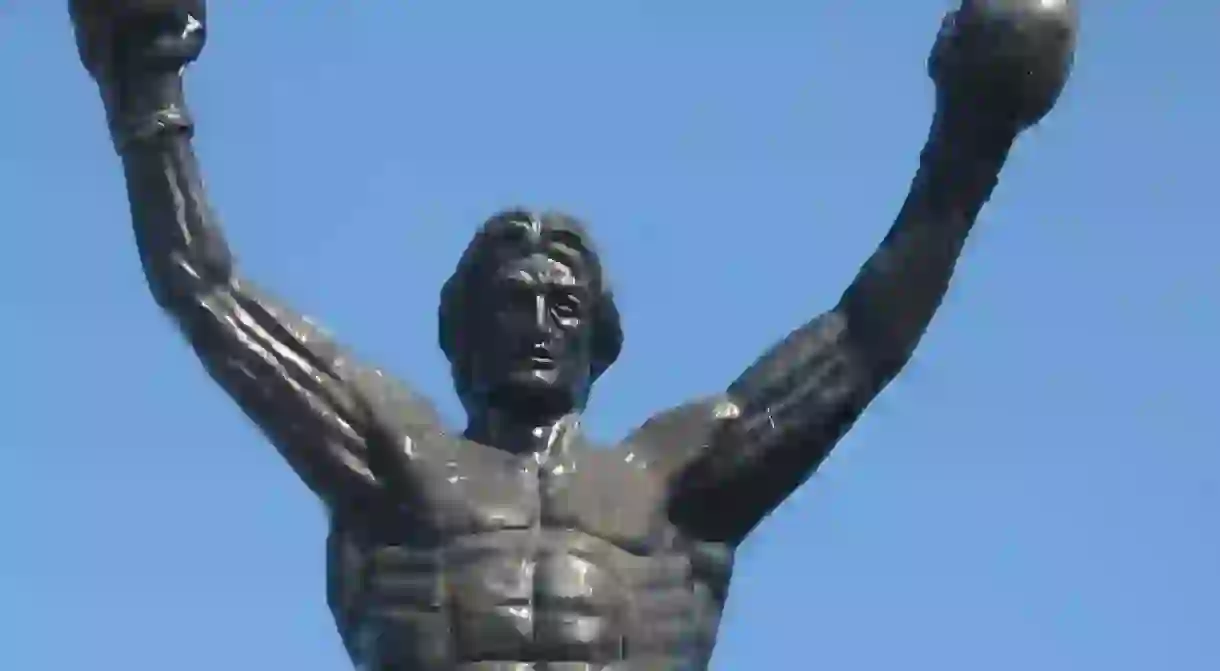

The Rocky statue

The eyes of the world finally turned towards this small corner of Vojvodina, a short drive from the border with Romania. The town held its first ever international press conference, and a local journalist even posited the idea of Rocky 7 being filmed in the town. Thousands were in attendance for the unveiling, and Žitište had its moment in the sun.

Is it strange that there is a Rocky Balboa statue in an unknown Serbian village? Of course it is. Monuments are usually erected in honour of men and women of the real world, individuals who helped propel a society forward in their own inimitable way. But the other side of the coin shows that it isn’t so strange at all, that the ideals encouraged by the Rocky movies are universal. Sylvester Stallone’s legendary character succeeded in spite of his limited ability and means, achieving the impossible against all the odds.

As a Žitište native poignantly said, ‘We are all Rocky’.