The Grisly Story of Serbia's Skull Tower

Centuries of vicious occupation will always throw a grim story or three. The very nature of medieval subjugation and liberation lends itself to the worst excesses of the human mind becoming a reality, and the famous Skull Tower in Niš comes straight from this playbook. This is the full story of Serbia’s most grisly monument.

The occupation begins

Despite centuries of strength and development behind it, Serbia was in a vulnerable state by the time the 14th century came around. The confidence of the Kingdom was shot, a situation not helped at all by the ever increasing strength of the neighbouring Ottomans. It was a matter of time before the Islamic Empire invaded, and invade it did. The southern city of Niš fell in 1385, passing back and forth before the Ottomans consolidated their gains in 1448.

Then, 241 years of misery began. Horrific stories of Turkish atrocities abound, many of which were chronicled by travellers passing through the area at the time. The city changed hands a few more times during the 17th and 18th centuries, but independence was a long way away.

The First Serbian Uprising

The empire was weakening, and uprisings were inevitable. The First Serbian Uprising began in February 1804, although the name of it should tell you all you need to know about its success. The Serbian rebels were poorly organised and beset by infighting, those in charge scrambling for power as the fighters were left in a hopeless situation.

Stevan Sinđelić found himself in such a position at the Battle of Čegar in May 1809. His army of 8000 men was woefully outnumbered, and they were soon overwhelmed. Sindelic knew that unspeakable horrors awaited his men if they were captured, so the man from Svilajnac decided to take drastic action. As his trench was overrun, he shot at a gunpowder keg and caused a huge explosion, killing everyone in the vicinity.

The building of the tower

Vizier Hurshid Pasha wasn’t exactly overjoyed at this show of patriotic defiance, so he ordered the heads of the rebels be removed from the corpses, before being skinned and stuffed and sent to Sultan Mahmud II. The Sultan presumably appreciated the offering, before sending the heads back to Niš to be put to use.

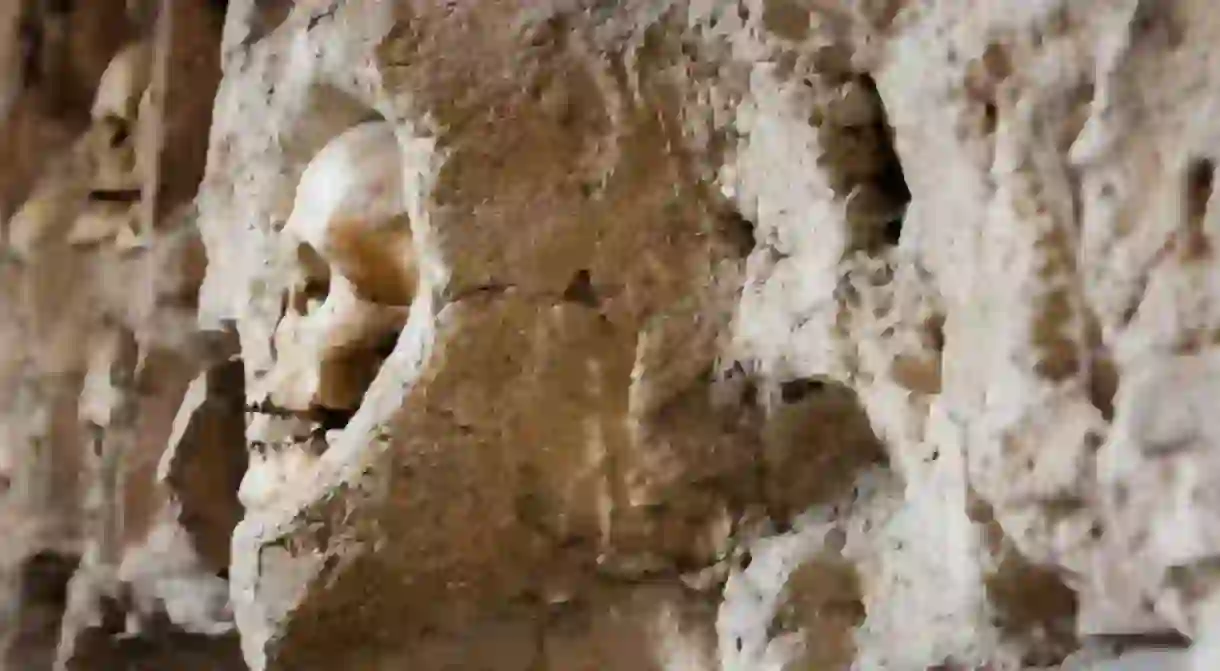

The Skull Tower was thus built in the city. It stood some four-and-a-half metres high, 14 rows of 17 skulls on four sides, numbering 952 dismembered domes. This wasn’t unique for Ottoman conquered lands, and such monuments were often built in an attempt to install fear and terror into the hearts of the locals. It worked.

Well, mostly. The skulls often fell out of the tower, and many were also stolen by thieves and distraught relatives, the latter of whom believed they could recognise the heads and took them away for burials. The skulls mostly stayed in place however, striking fear into the souls of any Serb who dared look its way.

A monument to sacrifice

With the tide well and truly turning against the Ottoman Empire, the last governor of Niš made the decision to remove the skulls. By the 1860s they were achieving little other than fostering resentment amongst the local Serbs, the fear long gone. Niš returned to Serbian hands on January 11, 1878.

A chapel was built around the tower, and the search for the lost skulls was on. Destroying the tower was never a question. It was imperative to keep it standing as a reminder to future generations of the sacrifices made by their ancestors towards the liberation of Serbia. The Skull Tower (Ćele Kula, in Serbian) thus stands as a silent monument to struggle. Less than 100 skulls remain, but this is still the most important single monument in Niš today.