The Grand Inquisitor: Dostoyevsky’s Radical Fiction

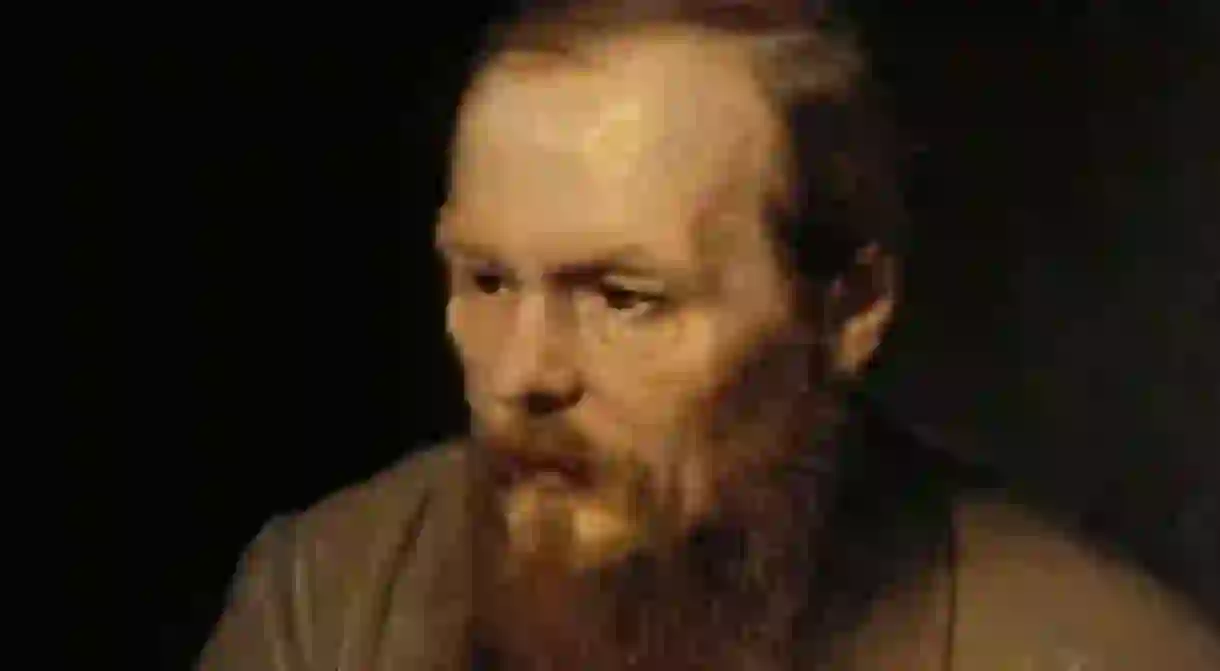

Russian novelist Dostoyevsky is considered one of the all-time greats of world literature. His radical work engaged with grand philosophical questions about religion, politics and morality, whilst also prefiguring many of the modernist tropes which would define 20th century fiction. But are these epic philosophical interrogations still relevant today?

Fyodor Dostoyevsky is routinely hailed as the greatest writer to have ever lived. Works such as The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov reflect a turbulent era in Russian history, when the radical politics that would come to dominate the 20th century fought with an intense Orthodox Christianity for the hearts and minds of a polarised country. Translated into numerous languages, his great novels have influenced writers all around the world for well over a century, and inspired everything from existentialist to dystopian to ‘Beat’ Generation literature. The modern novel however, is a much-changed beast and our concepts of social and spiritual responsibility are far removed from those of Dostoyevsky’s day. Due to this changing environment, recent critics and writers have looked not only to re-evaluate Dostoyevsky’s standing, but also to question whether his great works, so inspired by the tensions of their time, are still relevant today.

Dostoyevsky’s long and tumultuous literary career can be split into three distinct phases. Each of these was marked by calamity, poor health and bereavement, but they are separated by the quality, content, and influence of the works produced. Beginning with Poor Folk (1846), it was second novel The Double, released later that same year, which proved to be the defining moment of this first, contrasting phase. Having been initially hailed as a genius, Dostoyevsky was devastated when the critics derided The Double as the work of a Gogol plagiarising buffoon. He drifted aimlessly after this very public rejection and in April 1849, having sought solace in the sphere of radical politics, Dostoyevsky was arrested for ‘plotting to subvert public order’ and sentenced to death by firing squad. Although this was later rescinded, Dostoyevsky was given four years hard labour and conscripted into the army. He would not return to St. Petersburg for 10 years.

When he did return, Dostoyevsky was a changed man. Epilepsy had taken hold of his fragile health, and a tortured Christianity had replaced his once radical politics. He was determined however, to re-build his literary career. First Humiliated And Insulted (1861) and then Notes From The House of The Dead (1862) went someway toward restoring his battered reputation, but it was the brooding, manic, darkly comic, Notes From Underground (1864) that saw the end of what could be considered Dostoyevsky’s wilderness years and the beginning of his much celebrated and influential ‘later’ phase. Like much of his work during this ‘later’ period, Notes From Underground is often used as an example of his finest writing. Signaling a shift towards the psychologically charged, socially inquisitive novels that would dominate his later work, the true worth of this intense, almost overbearing novella, is the catalytic part it played in propelling Dostoyevsky towards his great works.

The beginning of this new era in Dostoyevsky’s life coincided with the critical acclaim his great rivals, Leo Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev, revered for their novels War and Peace, and Fathers and Sons. Seeing their success and using it as inspiration to surpass them, Dostoyevsky wrote the first of his ‘four great’ novels, Crime And Punishment (1866). Set during a stifling St. Petersburg summer, this claustrophobic, enthralling cat and mouse tale, is one of those rare novels that transcend traditional genre barometers and become something uniquely their own. Exploring ideas of free will, social justice, and spiritual redemption Crime and Punishment is arguably Dostoyevsky’s most philosophically enduring work. Tight, relentlessly paced, the novel was a huge success for an exhausted Dostoyevsky, who left Russia for Europe shortly after. Travelling extensively throughout the ‘West’ this, like many periods in Dostoyevsky’s life, proved to be an exercise of strength and determination during a time of great struggle.

Plagued by frequent epileptic seizures and a dire financial situation, exasperated further by his gambling, Dostoyevsky began work on what would eventually become his much acclaimed, but flawed classic, The Idiot (1868). Elusive, frustrating, The Idiot is Dostoyevsky at his most tragic, with no redemption, no hope, as the positively good man, the Christ-like Prince Myshkin, is tormented in a world of materialism and obsessive love.

More a melodrama of ideas than the grand tragedy planned, The Idiot is the work of a man questioning his faith, and was received coolly by an audience still captivated by its predecessor. Regardless of this it is today recognised as containing some of Dostoyevsky’s finest writing, and was a favourite of the author himself, but if The Idiot was Dostoyevsky at his most artistically and spiritually conflicted, then Demons (1872) was him at his most reactionary.

Partly inspired by the murder of a student, the tragic yet comic Demons was an attack on the increasing popularity of Nihilism among Russia’s youth. Like with much of Dostoyevsky’s works, critics are divided, with some proclaiming Demons as the best political novel ever written, and others seeing it is as the weakest of his ‘four great works’. In the character Stavrogin however, a nihilistic, depraved nobleman, Demons boasts arguably Dostoyevsky’s most interesting and complex creation. It is through Stavrogin Dostoyevsky explores notions of evil, debauchery, suicide, and his own feared consequence of a heightened political and spiritual liberalism. At the time, the novel was condemned by the politically minded youth as Dostoyevsky playing to the conservative crowd, but it also marked the end of a decade of unparalleled productivity, in which Dostoyevsky exercised many of his own great torments and ideas. It would be eight years before Dostoyevsky released his last influential masterpiece.

Arriving on the back of his famous Pushkin speech, The Brothers Karamazov (1880) came at a time when Dostoyevsky’s popularity had never been higher. Struggling at the time of writing with the loss of his young son, Dostoyevsky’s grand tale of murder, lust, family responsibility, and divine justice, is elevated by a stark, unyielding sense of longing, and owes much to the themes and ideals provisionally explored in the farcical, but largely forgotten The Adolescent (1876).

Focusing primarily on the strained and competitive relationships between the hedonistic Fyodor Karamazov and his sons, Dostoyevsky’s symbolic novel manages to weave complex, philosophical insights into the conflicts that torture humanity, while simultaneously operating as an entertaining who done it. Not long after the release of The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky died. The novel itself is still regarded as one of the finest ever written, and is perhaps Dostoyevsky’s most fully realised work.

Since his death, Dostoyevsky’s legacy has been widely debated. During much of the last century his work was largely ignored in his native Russia, and for every influential writer in the ‘West’ that acknowledged the debt modern fiction owed, there were detractors who mocked his pious, unsophisticated prose. To dismiss Dostoyevsky based purely on stylistics however, does him a great disservice. In fact, the spirit of his writing can be traced right through the cannon of 20th century literature. It is there in the God-fearing tone of William Faulkner’s Southern Gothic. It is in the character driven, existentialist explorations of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone De Beauvoir. Even the bleak, paranoid, post-modernism of Don DeLillo and the nihilistic satires of Brett Easton Ellis have their roots firmly in the ground of Dostoyevsky’s great work.

Of course, it is rare for today’s younger writers to discuss, let alone champion Dostoyevsky’s influence. This is largely due to this great debt being ignored. His novels are seen not as the intellectually challenging pieces they once were, but as overblown, religiously dogmatic melodramas. What is often forgotten though, is how his writing warns of the dangers posed by radical politics, social division, and nationalism. In fact, for a writer who once famously said ‘Each of us is responsible for everything and to every human being,’ the question should not be whether Dostoyevsky is still relevant, but how we preserve his timeless, thought provoking masterpieces of conflicted humanity.

By Reece Choules