Read an Excerpt from Chechen Writer Zalpa Bersanova's Novella 'The Price of Happiness'

A young woman plays on a piano despite being threatened at gunpoint to stop. This excerpt from Zalpa Bersanova is the Chechen selection for our Global Anthology.

Laura had passed her entire life in a world of dreams. She dreamed of being beautiful, but was decidedly plain. She dreamed of living in a big house, but lived in a shack. She dreamed of having a large family, but had only her elderly parents.

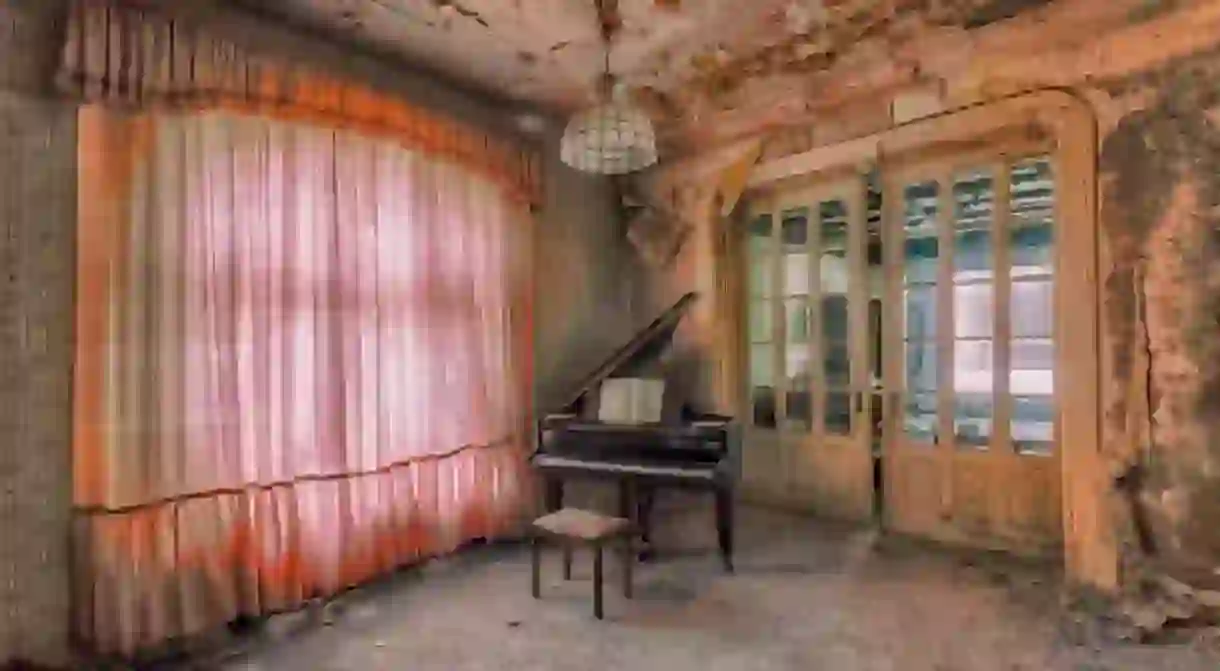

Then the war came and took away from her even the house and her elderly parents, leaving her all alone in the world. Just her and a rather ancient piano, which by a fluke had survived the bombing. The piano was a present which her music teacher had given to her best pupil, before getting out just before the war began.

Now her best pupil sat for days at a time, playing the piano which was sticking out of the rubble which had buried her parents.

The disaster which had befallen her was too great for her small mind to take in. She had the strength neither to weep nor scream, so she just sat there playing whatever came into her head. She played so that the music should blank out her pain.

There was nobody to comfort her. All around was so much distress that other people could barely come to terms with what had happened to them personally.

The bombing of the city intensified. Its inhabitants hastily buried those family members who had been killed and, gathering up whatever they most prized, abandoned the city.

As they left, each of them tried to prise the girl away from the piano and take her with them, but she just looked vacantly ahead and said nothing. They decided she had gone out of her mind, and shook their heads in sympathy and tut-tutted, but could think of nothing else to do, and Laura was left behind, all alone in the deserted street.

This frail girl playing on her wrecked piano must surely touch the heart of anyone. Anyone, that is, other than Them.

Attired like pirates, they moved in to help themselves to anything they remotely fancied: everything else, they simply destroyed.

Thin little Laura with her cauliflower ears and huge, frightened eyes they did not fancy, so they decided to destroy her.

“Waste her!” a ruddy muzhik ordered the squaddies, pointing at Laura.

An obedient subordinate tried to drag the girl away from the piano, but she held on so tightly that it looked as though they would have to shoot her together with the crippled instrument.

“Hey, she’s more stubborn than she looks, and strong!” said the pirate who was trying to pull her away.

“Leave it at that!” their officer ordered.

He turned to Laura:

“Come on, play something to cheer us up; it’s grim enough here without you and your funeral marches.”

“We’ll let you live for as long as you keep playing, but if you stop, it’s the funeral march for you,” said the pirate, glancing to see how the officer would take to his bright idea.

The officer smiled appreciatively.

Laura didn’t know how long she would have to play for these people—a day, two, a week, or a month? But she was glad of even this twisted chance of survival.

She started to play one thing after another, beginning with Kalinka and working through her entire repertoire, including the Lezginka. The pirates cheered up and decided not to kill her, and Laura was willing to play for them night and day if it would keep the soldier from repeating the order to “waste” her. The boisterous tunes grated on her ear and turned a knife in her heart.

Unfortunately for her, more soldiers soon arrived. They were hungry and mean, and had wounded with them who were groaning in agony. Those who were dragging the injured swore so foully that Laura wanted to cover her ears, but feared to take her hands from the keys.

Suddenly a superior officer shouted at her, “Stop that racket!” and slammed down the lid of the piano on her fingers as hard as he could. Her whimper mingled with the protracted jangling of the strings.

She tried to look at her fingers which had gone numb with pain and wondered fearfully as she looked at the officer what his next words might be. She hoped she didn’t know.

Luckily, just then they lost all interest in her. Some more pirates appeared and hurriedly reported that there were “ghosts” nearby. They had already occupied the station and would soon be here.

“What are we going to do with this pianist?” the one who had tried to pull her away from the piano asked, nodding towards Laura.

“Waste her!” The new officer barked. The pirate made no effort to conceal his delight, and was reaching for his rifle when shots were heard very close to them.

“Lay off! Leave her alone to play if she wants to. What harm’s she doing?” said a soldier who had dragged in a wounded boy, putting his hand on the rifle barrel.

Then, for a while, she was once again all alone in the world.

Zalpa Bersanova is a Chechen ethnographer and the author of several works of journalism and fiction. She was nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize. This excerpt was translated by Arch Tait and republished courtesy of Index on Censorship.