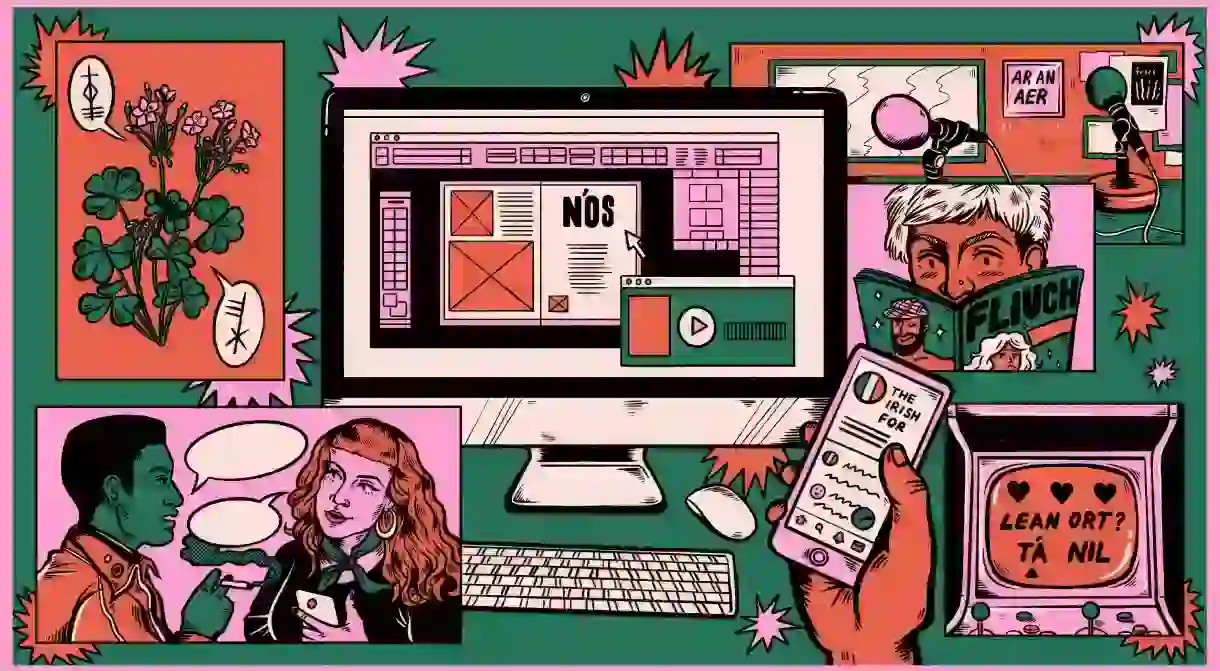

How Digital Media Is Bringing Ireland's Ancient Language Online

Irish has sometimes been viewed as a forgotten language, irrelevant to modern life; however, new media such as podcasts, Twitter accounts and online magazines are proving this assumption wrong.

Despite the fact that less than half the population of Ireland actually speak it, the Irish language is flourishing in the media thanks to the digital age. Propelling this revival are passionate advocates for Gaeilge (Irish), who are finding ways to bring it to an ever wider and younger audience.

“In my creative practice, language and landscape are absolutely intertwined,” says the poet Annemarie Ní Churreáin, who grew up on the boglands of northwest County Donegal. “I come to poetry knowing that my native Gaeilge was first inscribed into stone and bark in the form of Ogham (the Early Medieval Irish alphabet). If we are serious in Ireland about living in harmony with the wild environment, we need to take seriously Gaeilge as a way of accessing ancient knowledge, folklore and practical tips for living well.”

Ní Churreáin, whose highly acclaimed debut collection Bloodroot came out in 2017, describes her first language as “something I feel more and more emotional about”. She believes that we in the modern world have much to learn from Irish – one of the world’s oldest surviving languages, with the most ancient vernacular literature in Western Europe.

“Embedded into Gaeilge is a naturally open and inclusive way of being in the world,” she explains, using the word ‘teaghlach’ as an example. Usually translated as ‘family’, it actually refers simply to all the people within the household – a broader, more welcoming idea. “In terms of roots and community, a whole world of wisdom is being lost – quite literally – in translation,” she says.

Still the Republic’s official first language – and a compulsory school subject – Irish is spoken by 39.8 percent of the population according to the 2016 census. Just 1.7 percent use it daily. So scarcely is it spoken that it’s currently classified as ‘definitely endangered’ by UNESCO.

Keen to remedy this is Darach Ó Séaghdha, author of Motherfoclóir: Dispatches From a Not So Dead Language (2017). The book grew out of his @theirishfor Twitter account, which provides tens of thousands of followers with “smithereens of Irish, translated with grá [love] for your pleasure”. The book won Popular Non-fiction Book of the Year at the 2017 Irish Book Awards, and Ó Séaghdha has been praised for his fresh, funny approach. (A recent tweet warned that “‘Carán’ is an Irish word for darling; not to be confused with ‘carrán’ which means the layer of thick scum on top of buttermilk.”)

But there’s a poignant story behind Ó Séaghdha’s motivations. He started @theirishfor in early 2015, a few months after getting married. “I hadn’t been thinking about Irish for a while,” he says, but sad circumstances brought it back to the forefront of his mind. “My dad was going to be too ill to make a speech at the wedding, and I was also thinking that I wouldn’t have much time left to talk to him about all the things he wanted to talk about. I wanted to know why Irish was something that was really important to him.”

Searching for an Irish reading for the ceremony, Ó Séaghdha began stumbling across beautiful words and phrases and speaking to his father about them. “I started recording what I was learning, and set up the Twitter account, which got popular very quickly. It turned out that a lot of people had the same interest in it as I did.” He’s since launched a popular podcast – also called Motherfoclóir – which he says easily found an engaged audience. “Even people who are only marginally interested in Irish get a kick out of it, as well as people who know more Irish than I do.”

Others have similarly picked up on these shifting attitudes. “The old stigma of Irish being the language of the past, we’re finally losing that,” says Tomaí Ó Conghaile, founder of NÓS, an award-winning Irish language culture and lifestyle magazine based in Belfast. “That old post-colonial influence is sort of leaving us, we’re growing out of it. In the country in general, and also in our culture, we’re becoming more confident and more positive, and I think that’s reflected in how people view the language.”

In 2008, Ó Conghaile saw a gap in the market for a contemporary Irish-language magazine, focussed on “popular issues: music, film, technology, travel, sex, everything”. With a team of friends, he created and designed such a product, circulated it online, and soon had more than 300 subscribers, at which point NÓS went to print. More than a decade later, it’s morphed into an online magazine with occasional special print editions, and a network of contributors in Ireland and abroad. It’s had no problem finding a readership, primarily among people between the ages of 20 and 30 – further evidence of a millennial audience seeking a connection to the Irish language.

Raidió RíRá appeals to an even younger demographic. The internet radio station plays chart hits as well as Irish language music, interspersed with sports and film news entirely as Gaeilge (in Irish), and runs regular workshops in schools around the country, giving young people the chance to see how radio shows are made.

“We reach a lot of people through schools and summer courses in the Gaeltacht (Irish-language speaking regions in Ireland),” explains station manager Niamh Ní Chróinín. “For people who are in school, especially those studying for exams, it’s an enjoyable, fun way for them to be listening to and picking up more Irish.” Raidió RíRá had its highest ever audience in 2018, with almost 20,000 monthly online listeners, plus more through its app.

Clearly, the modern media in its various forms is helping to bring Irish people closer to their history and roots. The language is appearing in new forms and being used to communicate contemporary issues, such as in young adult fiction books like Máire Zepf’s Nóinín, which explores the potential perils of online dating. Video games are being translated into Irish, and Irish-speaking virtual assistants are on the horizon. There’s even an Irish-language porn magazine.

The only problem seems to be meeting the growing appetite. “It would be great to see more independent people coming out with their own content… because there is a demand for it,” says Dónal’s Ó Gallachóir of Peig.ie, a website that provides Irish speakers and learners with news, job notices, and a map of classes, conversation groups, and other events in their area. According to Ó Gallachóir, Peig.ie has seen a consistent increase in users since its founding in 2015. “The numbers are only going one way, and that’s up.”