Geothermal Pioneers: How Does Geothermal Energy Fuel Iceland?

We’ve all seen videos of erupting geysers and captivating pictures of geothermal pools like the Blue Lagoon, but thermal energy is more than just a tourist attraction. In fact, some of Iceland’s pioneering industries are harnessing the power of natural energy to help revolutionise the way they work in Reykjavik.

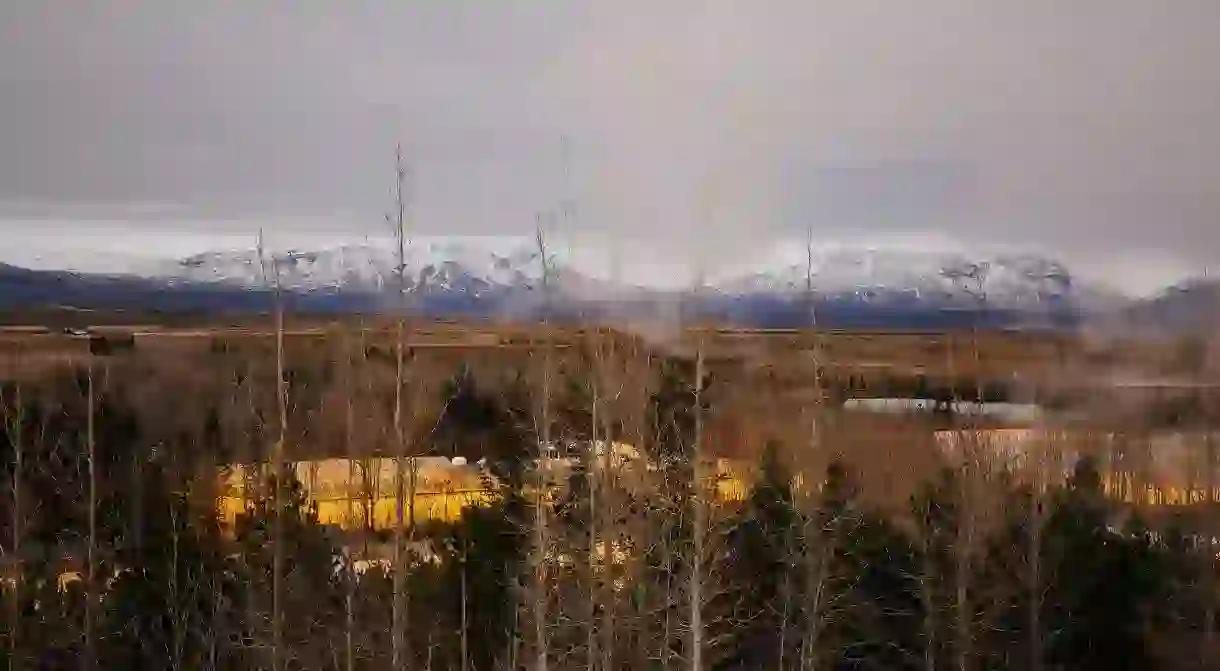

The volcanic geothermal energy that sits under Iceland’s towering glaciers is a valuable source for the tourism industry as well as local businesses. This isn’t a new phenomenon though: the country’s first geothermally heated greenhouses were built in 1923. Culture Trip spoke to two local businesses to find out how they’re benefiting from the use of geothermal energy.

Friðheimar greenhouse and restaurant

Located in Reykholt, Friðheimar produces three varieties of tomatoes in its 5,000 square metres (54,000 square feet) of electrically lit greenhouses each year, with a yield of around 300 tonnes (300,000kg) of tomatoes (around 18 percent of Iceland’s total tomato market). And according to Rakel Theodórsdóttir, the marketing and quality manager at Friðheimar, “the farm uses around 100,000 tonnes of hot water a year to heat the greenhouses and aims to grow tomatoes with the best taste quality while also maintaining eco-friendly standards”.

Geothermal energy is used to heat and sterilise the soil and greenhouses, and to produce carbon dioxide and electricity. Water from the nearby hot spring flows into the Friðheimar greenhouse, where it circulates through kilometres of pipes in order to heat it to the right temperature. Once it has cooled down to 43°C (109°F), it returns to the spring to be recirculated.

Friðheimar also doubles as a restaurant which works to keep the tomato production as local to Iceland as possible. “All electricity used at the site comes from Iceland’s green electricity sources, carbon dioxide comes from natural steam at Haedarendi and growers use volcanic tuff, such as pumice from Mount Hekla, as a substrate in place of soil,” Theodórsdóttir says.

Ölverk Brewery

Seven power stations in Iceland harness this particular use of renewable resource to create 25 percent of the island’s energy – helping heat up homes, keep pavements and roads clear of ice and snow, and aiding businesses and industries. At Ölverk Brewery, however, the method is used to produce beer.

The town of Hveragerði – which sits on the edge of the mid-Atlantic ridge and produces a lot of renewable energy – is home to a brewery that uses hot steam from the boreholes in and around the town to create its renowned beers. Opened in 2017, the team has produced around 100 different brews – despite being one of the smallest craft breweries in Iceland. Run by CEO Laufey Sif Lárusdóttir, her fiancé and brewmaster Elvar, as well as friend and co-owner Ragnar, they produce around 300 litres (528 pints) of beer in each brewing session with a maximum capacity of 30,000 litres (52,800 pints) a year. “Our whole brewery was set up so the geothermal steam could be used as the main energy source in the brewing process. We use the geothermal steam when we’re boiling the wort and to heat up the water that is used when making the beer,” says Lárusdóttir.

Ölverk Brewery’s unusual brewing method hasn’t impacted the quality or taste of the drink. If anything, it has proved to be highly appreciated amongst visitors. Lárusdóttir says, “craft beer fans and visitors to Iceland really appreciate the high quality of the fresh, Icelandic water used in the beer.”

Not many people are aware of the different ways you can use geothermal energy and, according to Lárusdóttir, “this way of making beer has opened the eyes of many people and now the use of alternative energy in the brewing industry is something more people are thinking about”.

Next time you visit Iceland, be sure to experience the many ways that geothermal energy is used. Whether you’re soaking in the naturally heated springs, biting into an Icelandic-grown tomato, or washing down your dinner with a pint of Ölverk’s finest, think of the hot steam that helped create these unique Icelandic experiences.