Who Are Hungary's 'Hipster' Patriots and Why Should You Care?

A new political movement is making its mark in Hungary, with the younger generation mobilising to create a platform from which to put forth their views and represent their political beliefs. Momentum Mozgalom (Momentum Movement) has already stopped the Olympics; now, the party is now campaigning to take a seat in parliament.

At the beginning of 2017, a small political movement managed to transcend its size and cause Hungary to drop its bid to host the 2024 Olympics, gaining over 250,000 signatures on a petition to force a referendum on the issue. The government pulled its bid before this could be held in an effort to prevent any future unrest.

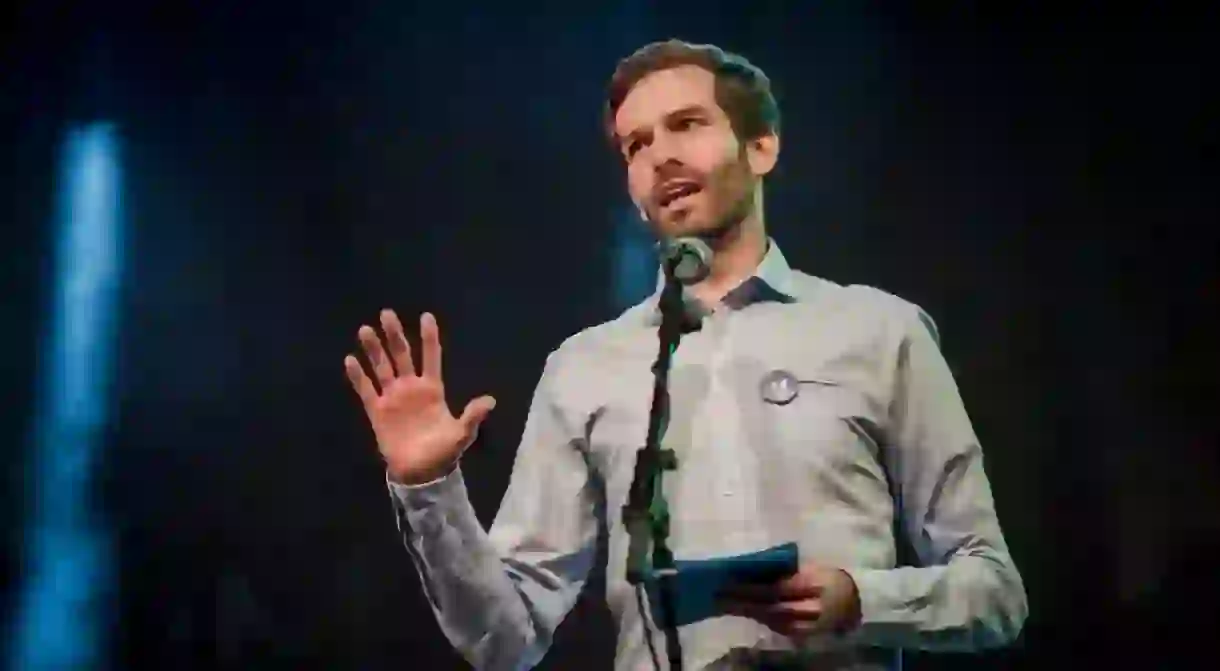

The country’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who threw his support wholeheartedly behind the bid, insisted Hungary could have won the referendum, and blamed the group for destroying the country’s Olympic dream. The campaign’s success suggested otherwise and was enough to propel the group behind it onto the public stage: entitled Momentum Mozgalom (Momentum Movement), it gained an audience for its message and its leader, András Fekete-Győr, became a popular interviewee. But what exactly is Momentum – and what do its members want?

Created in 2016, Momentum is a young movement formed of the self-described ‘new political generation’. Failing to identify with any of the parties which existed in Hungary at the time, the group was born from a desire to provide an alternative. Its members have been dubbed ‘hipster patriots’, and there are now around 1,100 of them; the party’s offices are found in a basement in Budapest’s seventh district, while discussions and events are often held in bars, parks and outdoor gardens across the city. The group often organises festivals, at which live music, political speeches and discussion groups can be found alongside one another.

Their campaign to stop the Olympics, entitled NOlimpia, centered around a petition to force a referendum on the issue. 138,000 signatures were needed; 266,000 were obtained. It was an almost unprecedented success and gave Momentum the opportunity to promote both itself, and what it stands for as a party. With the initial rush of victory subsiding, the movement has a new goal – and its sights are set on parliament.

Hungary’s current government is the conservative Fidesz party, led by Viktor Orbán. A politician who cut his teeth with the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, comparisons have been drawn between him and András Fekete-Győr, thanks to their shared status as young activists at different times. The Fidesz party currently holds a strong position in power, with government-friendly media outlets and a voting system which works in its favour. Nevertheless, Momentum has made it its mission to challenge this authority. The country will hold parliamentary elections in 2018 and the small party hopes to make its entrance into government, even though Fekete-Győr acknowledges that considering a long-term plan is more realistic. To get votes, however, they will need to convince people they’re worth supporting. So, what exactly does Momentum want?

For starters, the movement hopes to give a voice to those ‘political orphans‘ who feel unrepresented by the options previously available. A strongly pro-European party (something the current government is not), the group holds five issues at its heart: healthcare, education, transport, housing and the economy. Its campaign against the Olympics was based on the premise that the country cannot afford to spend such a huge sum of money on the games when it has many domestic issues to take care of first. They refuse to work with any other political parties, speak out against the perceived political elite, and hope to lead Hungary into the 21st century, modernising its infrastructure and emphasising the importance of the digital world.

The movement is no doubt attractive to those who currently feel left out of Hungarian politics, alienated by the increasingly conservative policies of the current government. Viktor Orbán is keen to promote the idea of an ‘illiberal state’ and has put forward a number of protectionist, nationalist policies. Over the last few years, the government has run tax-payer funded campaigns against immigration; in 2016, it held a referendum asking whether Hungary should accept the EU’s refugee quota. Having already built fences to keep refugees out of the country, the government campaigned for a ‘no’ result; turnout was ultimately less than 50%, lower than needed for the referendum to be valid and hinting at a dissatisfaction with the government’s stance.

In the spring of 2017, disappointment with the country’s current leadership bubbled to the surface in the form of a number of protests against its plans to introduce legislation which would effectively close the Central European University, located in Budapest. Many see the government as corrupt and increasingly controlling; press freedom is restricted, with many news outlets controlled by pro-government organisations.

http://instagram.com/p/BS0V1qpBP0U/?tagged=istandwithceu

In this climate, under an increasingly right-wing government, it is perhaps unsurprising that a party such as Momentum should achieve some level of popularity. The younger generation, many of whom have spent time living abroad, are rebelling against the perceived elitism and conservatism of the current system: something the movement speaks out against. However, Fidesz still enjoys widespread support throughout the country and challenging its power is likely to be a long process. The party regularly maintains a 20-point lead in opinion polls; the far-right party Jobbik is currently its closest competition.

This isn’t stopping Momentum: while polling at under 5%, the party still hopes to gain ground over the next year and into the future. With a number of Orbán’s current policies having Europe-wide consequences (including his anti-refugee policies, his anti-EU stance, and his effective closure of the Central European University – which has prompted calls for Hungary’s European membership to be suspended), the emergence of an alternative is something which could have further reaching impact than just within Hungary’s borders.