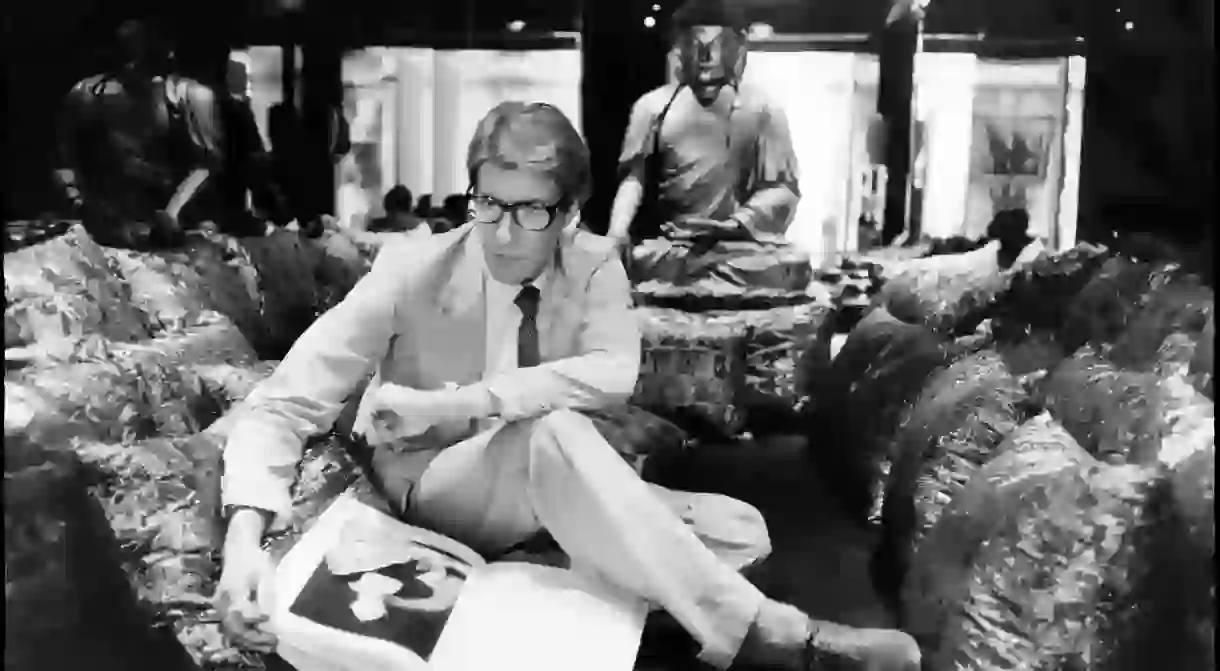

Yves Saint Laurent’s Exploration of Asia Was All a Dream

As the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris opens its doors to the 2018 thematic exhibit Dreams of the Orient, Culture Trip explores the prestigious designer’s interest in a continent he never experienced in person.

“Yves Saint Laurent never actually visited Asia before he started designing clothes that were influenced by its heritage style,” says Olivier Flaviano, director of the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris. But Chinese, Japanese and Indian influences infiltrated the late couturier’s work throughout his career. Dreams of the Orient is the museum’s 2018 thematic exhibit and it highlights the ways in which these inspirations manifested in his collections.

“I approached every country through dreams,” Saint Laurent once said. To the untrained eye, his lack of direct cultural experience may be hard to identify, but perhaps that’s because of the hours of detailed research he did ahead of each collection. “Saint Laurent’s designs were dreams, but they were awakened dreams,” says Falviano. “We have collated over 7,000 artefacts as evidence of that.”

Whether it be a reimagining of a floral design on a Chinese vase or the Indian-inspired precious jewels that the designer used as buttons, Asia and its art forms were present in varying degrees from as early as 1962 until 2002, when he died. Saint Laurent drew from art, film, music, text, theatre and home décor to create a vision of each country in his mind and the inclusion of these artefacts in the exhibit highlights his acute attention to detail. However, no matter how exacting Saint Laurent’s execution was, there is no denying that this exhibition celebrates a European designer who appropriated styles and influences from countries he never visited. For some, this will feel out of step with our more culturally conscious age.

Saint Laurent’s autumn/winter 1977 collection, Les Chinoises, comprised two contrasting interpretations of China. The first, named Imperial China, focused on the style associated with high social status. Fabrics were luxurious, colours rich and embroidery intricate, with plush fur trim adding further texture to already opulent designs.

The second – a “floral China”, as Flaviano calls it – was less steeped in grandeur but equally impactful, adorned with bird motifs, floral pattern and fruits. With this dual collection, Saint Laurent did not intend to directly recreate something historical, but to refocus it through a modern lens and make it wearable for the Western consumer.

“He was the only designer doing this kind of thing with such depth and meaning at the time,” says Flaviano. “Yes, he created beautiful clothing, but he also addressed social and political issues within his work.”

His spring/summer 1982 collection was inspired by India. “At a time when only men wore turbans and passed them down through family generations, Saint Laurent transformed them into a fashion piece for women. It was his way of giving women power,” says Flaviano. The same is true of his most iconic look, Le Smoking, which revolutionised the perception of the tuxedo as a womenswear look in 1966.

What Yves Saint Laurent did was so much more than design clothing. His collections were meaningful and designed to inspire and empower women. Each was historically authentic as well as culturally relevant, but it was the designer’s sense of creativity that brought the pieces to life.

“A picture book is all my imagination needs … to blend into a place or into a landscape,” the designer once said. “I don’t feel any need to go there. I have already dreamt about it so much.”

Dreams of the Orient is at Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris until 27 January 2019.