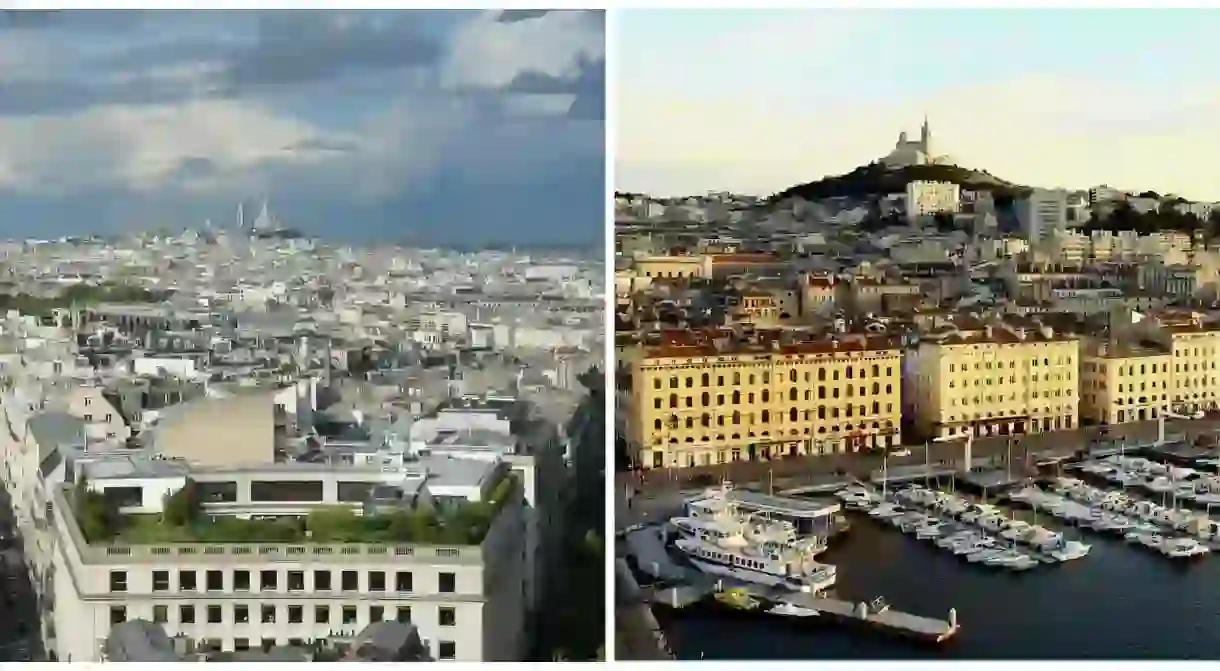

Paris Vs. Marseilles: A Rivalry On And Off The Pitch

On the surface, the rivalry between Paris and Marseilles is a pitched battle (sometimes quite literally) between two opposing football teams and their legions of die-hard fans. However, beneath the derisive chanting, flag-waving, and occasional parking lot scuffles, a genuine cultural divide exists between the two great cities of the north and south of France, one which encompasses issues of class, economics, governance, crime, and social integration.

Le Classique, or the Derby de France, is the most visible manifestation of the enmity between Paris and the self-proclaimed ‘real capital’ on the Mediterranean. Not only are the games between Paris Saint-Germain and Olympique de Marseille the most fiercely contested in Ligue 1, they are reputedly violent grudge matches between groups of supporters. A tough stance by the national league has all but stamped this out, but fixtures during the 1980s and ’90s often saw hooliganism usually reserved for the films of Nick Love. For Marseilles, a city with unemployment and municipal finance figures badly out of shape, the sporting excellence of their home side has been a persistent source of civic pride, one certainly worth defending.

The caricatures of Paris and Marseilles – peddled by the domestic and international media, as well as by a good number of locals – are drawn crudely along class lines. The first is a city occupied entirely by the bourgeoisie; a snobbish, elitist mass for whom the rest of the country is either a barren wasteland or seasonal playground, depending on the area’s suitability to leisurely pursuits. The latter is staunchly working class; the home, at best, of the cheeky chappy and chappettes and, at worst, the stomping ground for mobs of lowlife yobs and dangerous criminals, whose bizarre accents, in any event, render them incomprehensible. The reality, of course, is far more nuanced.

Until the 1960s, in addition to being France’s second city in terms of population, Marseilles also had the busiest port in Europe, through which the riches of the colonial empire flowed. Decolonization essentially emptied the city of its industry and it has yet to fully recover. The local unemployment rate remains stubbornly above the national average and it’s estimated that up to a quarter of the city’s population lives below the poverty line. The Paris region, on the other hand, produces approximately 30% of French GDP and 5% of the European Union’s. This regional disparity is largely due to the fact that France remains the most centralized country on the continent despite recent provincial infrastructure investment.

Its designation as the European Capital of Culture in 2013 represents the most significant recent effort to reverse Marseilles’ fortunes. The waterfront has undergone a €7 billion regeneration and now boasts Rudy Ricciotti’s MuCEM, the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée – the principal cultural element of a push to transform the city into a regional business hub. Serious numbers of jobs have yet to materialize.

Nevertheless, the choice of architect – an Algerian-born, Italian immigrant who studied at the local architecture school – is telling of the Marseilles character: the ingrained determination to celebrate its own successes regardless of the faults outsiders might see in it. For the design of Paris’ latest museum, the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the renowned Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry was chosen. Buildings on this scale, public or private, impact how residents think about their city and, while Gehry’s might symbolize Parisians’ outward-looking mindset, it’s hard to imagine they will ever connect with it in the same way their southern counterparts do with Riccotti’s.

It is said that in the Parisian imagination – which is to say, that of the white, wealthy, and wizened – Marseilles is a city run by North African gangsters, corrupt to its core, and where one is as likely to get murdered as looked at. It’s true that in its most impoverished districts, drug trafficking remains a problem but, globally, its crime rates are no higher than in other French cities and, by numerous metrics, it is safer than Paris. The fact that Marseilles locals embrace their reputation as the bad boys and girls of France has more to do with bravado than reality.

In fact, Marseilles’ homegrown rap scene, which celebrates the city’s cultural and racial diversity, has created social cohesion sorely lacking elsewhere in France. On top of this, the city’s patchwork of poor and better-off neighborhoods means that no one is left feeling cut off. On the contrary, Paris’ surrounding motorway has for too long acted as a physical barrier to effective social integration between the residents of the city and the suburbs. For proof, consider that in 2005, when rioting broke out in outlying parts of the capital and spread across the country, Marseilles remained uncharacteristically quiet.

Whether Paris or Marseilles makes for a better capital city is not something their residents are ever likely to agree on. That being said, it would be remiss not to mention that when the French sing their national anthem, it is La Marseillaise that fills their eyes with tears of pride.