A Brief History Of The Circus In France

While the history of other performing arts is well documented, serious attempts to delineate the evolution of the circus are few and far between. There is a popular misconception that spectacles of acrobats, clowns, stunt riders, and exotic animals are a direct descendant of Roman entertainment, sustained across the centuries by traveling communities and their shows, but the reality is a more modern affair.

In truth, the similarities between the Circus Maximus in Rome and the Cirque d’Hiver (Winter Circus) in Paris begin and end with their names and the ‘circle’ or ‘ring’ shape that this denotes in Latin. Antiquity’s largest venue is actually a much closer ancestor of the Longchamp Racecourse. The modern circus is just 250 years old and the invention of an Englishman named Philip Astley. During the Seven Years’ War, fought between 1756 and 1763 and out of which Britain succeeded France as the world’s dominant power, Astley distinguished himself as a talented horse trainer. He went on to found a riding school in London, whose 62-foot circular arena he called the circus (today’s international standard is 20 feet smaller). Astley taught in the morning and in the afternoon performed his ‘feats of horsemanship’, the first on January 9th, 1768.

The leap from equestrian show to full-on circus act was made two years later when Astley added acrobats, rope dancers, jugglers, and clowns in order to keep the crowds coming. In 1772, he traveled to Versailles to perform for Louis XV. The king’s reaction was such that Astley endeavored to open a permanent circus in Paris, a feat he achieved in 1782 with the Amphithéâtre Anglais. By the time of his death in 1814, he had established 18 more circuses in cities across Europe.

The traveling menagerie seemed the natural complement to the circus. Trained exotic species, especially big cats, soon entered the ring. It was at the Franconi family’s Cirque Olympique in Paris that the first performing elephant, Kioumi, was displayed to the public in 1812.

Well into the 19th century, acrobats remained the stars of the show. At first, they swung from slack ropes and later from a bar affixed between two of them: the trapeze. In 1859, French gymnast Jules Léotard presented his new act to the audience at the Cirque Napoléon (what is now the Cirque d’Hiver) in Paris, La Course aux Trapèzes, in which he flew through the air from one swinging bar to another. The flying trapeze made him famous across Europe as did his skin-tight outfits, which remain popular with dancers and extroverts.

In Europe, the circus – which had since become a global phenomenon – enjoyed its peak between the World Wars. At one time, Paris had four permanent circuses, all of which drew huge audiences. By the 1970s, all this had changed. Cinema and television had replaced it as the preferred form of entertainment, few performance innovations had been seen for decades, and animal rights had emerged as a societal concern. It was a time of crisis and many big names in the business went bankrupt. In 1978, the French government stepped in, transferring the responsibility of this 210-year-old tradition from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Culture. As well as a symbolic shift, this gave circus performers the same rights, such as access to funding, as other artists. Individuals were then able to take the time to develop new acts and through them the art form experienced a renaissance.

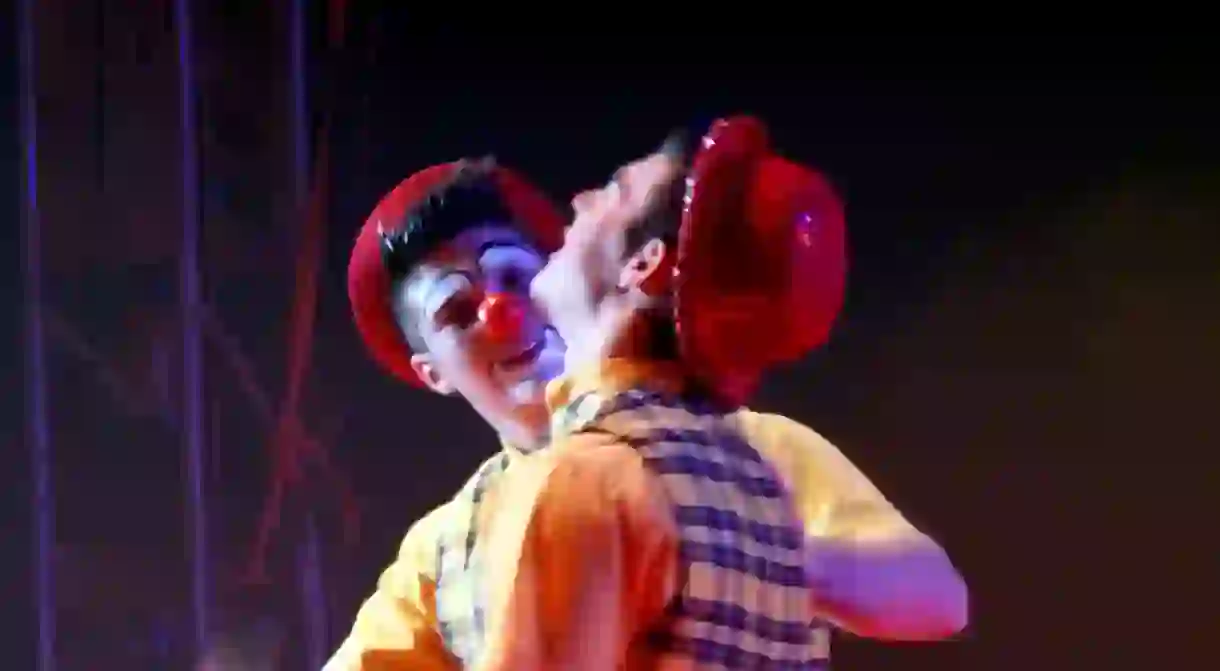

Contemporary circus, or nouveau cirque as it was called, was showcased at newly created festivals such as the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain (The World Festival of the Circus of Tomorrow) and young talent nurtured at schools like the Centre National des Arts du Cirque. Current estimates put the number of working circus artists in France at 450 and there are somewhere in the region of 1,000 shows per year. Traditional circuses still exist but it is the contemporary alternative – something more akin to a night at the theater or ballet – that draws the crowds to the big top today.