7 Dadaists Who Changed The Face Of Art

In 1920s Zurich, an international collective of disgruntled artists blamed the logic of capitalist Europe for the horrors of World War I. Searching for a moniker, they plunged a knife into a French-German dictionary, landing by chance on the word ‘dada’ (French for hobby-horse). The key characteristics of Dada are (a) total opposition to reason and (b) the embrace of chance. Here’s a crash-course on the seven most important artists in the movement.

Tristan Tzara (1896-1963)

Dada, in its rejection of order and hierarchy, had no leader; but if anyone comes close, it’s Tristan Tzara, a Romanian poet and performance artist who served as a sort of spokesman for the movement. He wrote a Dadaist Manifesto in 1918 in which he outlined the philosophy of Dada and the conditions under which it grew: “Logic is always wrong… Its chains kill, it is an enormous centipede stifling independence. Married to logic, art would live in incest, swallowing, engulfing its own tail, still part of its own body, fornicating within itself.” In his own output, he is perhaps most famous for his development of the cut-up technique. A method outlined perfectly in ‘To Write a Dadaist Poem.’ Cut-ups were developed further by American beatnik writer William S. Burroughs, and variations on it have been employed in lyric writing by David Bowie, Radiohead, Kurt Cobain, and even the Beatles (cutting up the very tape reels on Revolution 9).

Jean/Hans Arp (1886-1966)

Another founding member, Jean Arp – or Hans Arp, depending on whether he was speaking French of German at the time – was best known as a visual artist. A painter and sculptor of abstracts, his work was biomorphic (non-representational, yet evocative of natural forms). Just as Tzara employed chance, composing poems by picking words out of a hat, Arp did not start with an idea or subject as most artists do. Instead, he created his forms first and titled them after they were completed, letting the unconscious lead. The result reads like him trying to interpret the meaning of a given piece along with the audience. Arp was a truly unique artist. Not only was he a founding member in Dada, and later a significant surrealist; but he was a movement unto himself, one of those rare artists like Picasso or Dalí with an instantly recognizable flair all of his own.

Hannah Höch (1889-1978)

One of the few women working in Dada, Höch was a collage artist. A pioneer of the photo-montage technique, she took photographs from a variety of sources that would be considered unrelated, and combined them into artworks that were at once striking, surreal, and deeply meaningful. As was the tendency in Dada, her work was politically radical, but she went further than her contemporaries. One of the only women permitted the join the movement, her work dealt with themes of womanhood and feminism that the others did not touch. While the Dadaists paid lip-service to women’s emancipation, she saw the hypocrisy in how they treated her, with most of their accounts erasing her from history, save for Hans Richter, who described her primary accomplishment as the provision of sandwiches, coffee, and beer to the men. Nevertheless, her work was more serious than most, and as vital as any.

Hugo Ball (1886-1927)

Founder of the Cabaret Voltaire and writer of the first Dadaist Manifesto in 1916, most of Ball’s work was in the genre of sound poetry. In the same year as the manifesto, he performed the poem Karawane, which opens memorably with:

jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m’pfa habla horem”

(…and continues much the same until the final line) “ba-umf.

This could be confused with mad ramblings, but sound-poetry is actually a deeply considered method in experimental literature, where sounds of human vocalization – an omnipresent feature, though one usually relegated to the sidelines by meaning – are brought to the foreground by the removal of all else. Ball’s devotion to meaninglessness led to his eventual departure from the group after only two years, finding himself at odds with the overtly political intent of artists such as Tzara.

Man Ray (1890-1976)

As other artists at the dawn of the 20th century liberated painting, sculpture, and poetry from the confines of figurative representation, so did Man Ray liberate photography by developing the ‘rayograph’ (otherwise known as a photogram or cameraless photograph). The technique was achieved by placing found objects on a sheet of photosensitive paper and exposing them to light, resulting in jarring, shadowy images that were totally abstracted from reality. In true Dada fashion, the rayogram was arrived at by accident. While waiting for a traditional photograph to develop, Ray had carelessly placed some equipment on a sheet of photo-paper, Tzara spotted the accidental artwork, dubbed it a “pure Dada creation,” and the rest is history.

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971)

Hausmann, though also a poet, collagist, and performance artist, is best known for a work of sculpture entitled Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time), a creation that is immediately striking on first viewing, but becomes even more provocative when you learn of its intent. This manikin head, hewn of a solid wooden block is a reversal of Hegel’s assertion that “everything is mind.” For Hausmann, in his radical Marxist view, the situation is reversed. Man is empty-headed “with no more capabilities than that which chance has glued to the outside of his skull.” In raising such ideas, Hausmann succeeded in composing an image that shatters the Western conventions that the head is the seat of reason, positing instead that it is governed by the whims of brute external forces.

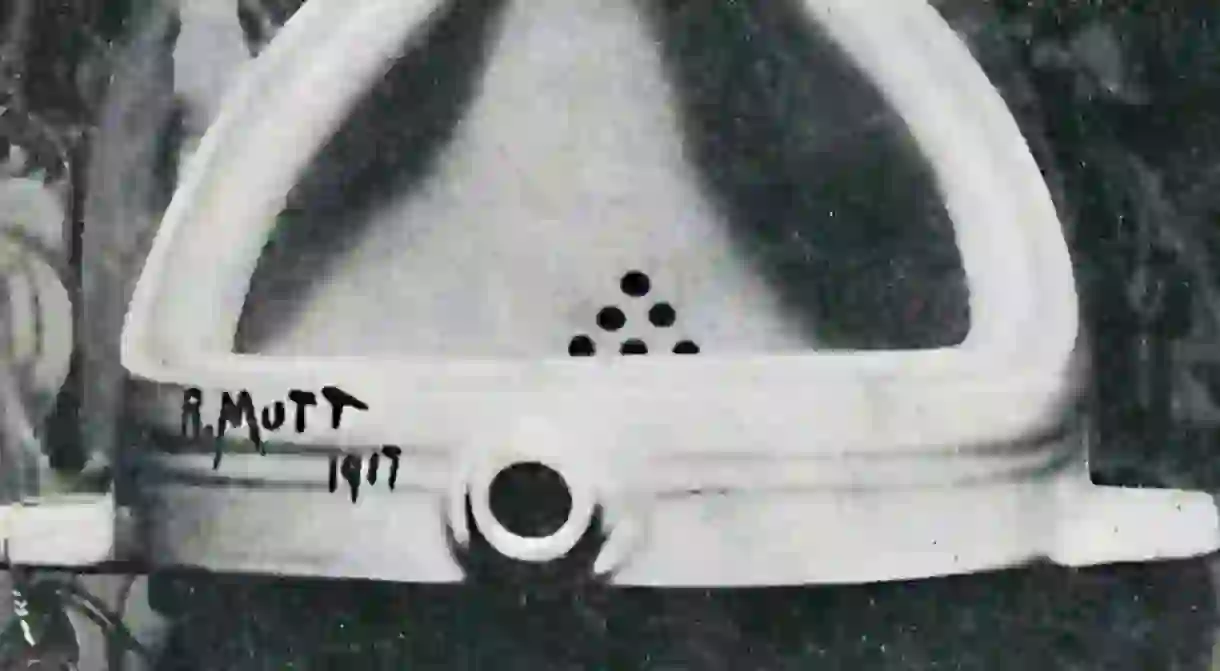

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Marcel Duchamp’s best known piece is definitely Fountain. Probably the best known artwork in the entire Dada movement, well known even to the most devout philistine as “that time some French fella put a urinal in a gallery and called it art,” Fountain consists of…well, a urinal that he found and submitted to an exhibition. But there’s more to it than that. Fountain was one of Duchamp’s ‘readymades’: pre-manufactured consumer goods that the artist signed, dated, and placed in a gallery, thereby turning the object into art. It was one manifestation of Duchamp’s wider purpose, which was to break from mainstream art, which he called “retinal” (existing only to please the eye), and moving instead into the mind. The influence on the Pop Art of Andy Warhol should be obvious, but Duchamp’s legacy goes far deeper, as one of the few people who can be said to have changed the course of history. Wildly successful in his attempts to lead art away from retinal pleasure, he heralded a new era. Where in the classical age, craft was of paramount importance, in the early modern era, it was style and aesthetics. Duchamp gave birth to conceptual art: the art of ideas. Marcel Duchamp asked the question: What is art?’ And we’ve been struggling with the answer ever since.