The First English Edition of this Book Visualises Life Under Nazi Occupation

Tragically, Charlotte Salomon—like far too many others—didn’t survive Auschwitz after being deported from France and sent there during World War II. However, her powerful art did, and the late German-Jewish artist transcends time thanks to her uncompromising testament of a twisted family curse, Nazi occupation in France, and choosing murder over suicide.

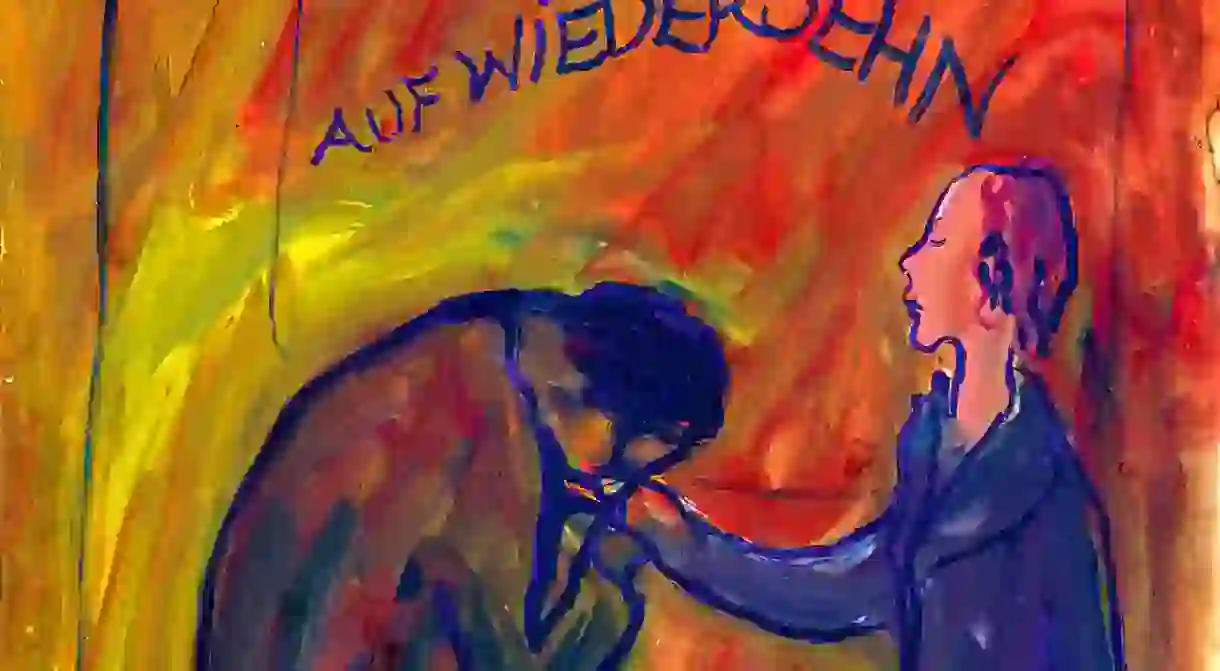

Goodbye Berlin

Charlotte Salomon was born in Berlin in 1917, the only child of bourgeois parents. Her mother died when she was little, and her father, a surgeon, subsequently married an opera singer and socialite. Salomon was attending Art Academy (not many Jews were admitted) but as the persecution closed in around her family, they moved to the French Riviera. After the declaration of war, they were rounded up and sent to a camp in Pyrenées, and later allowed to return to the Riviera, owing to her grandfather’s age and health. It is here that Salomon feverishly put together her opus, Life? or Theatre?.

A diary of strangeness

Since her world crumbled around her, Salomon clung to art as a life raft. When her grandmother took her own life, Salomon finally learned about the family’s curse: she came from a long line of suicides, including that of her own mother. Salomon painted and wrote to ‘create a story so as not to lose my mind’. The work is hard to label since she took to selecting 781 of her gouaches and hundreds of drawings, combined with overlaid text and musical notes in a sort of graphic script/novel that is part biographical and part lyrical. She completed Life? Or Theatre? in a single year with a sense of urgency perhaps arising from the precarious condition of Jews in Europe and a sense that her days were numbered.

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger

Life? or Theatre? is no Diary of Anne Frank. Salomon’s images are not focused on an account of Nazi oppression or the persecution of the Jews. Furthermore, Salomon’s world is painted in a more complex, nuanced, and deeply disturbing approach than Frank’s. Her depiction characters of her childhood, her own development as an artist, and her grandfather as a brutal manipulative and abusive monster are mixed and masked under fictitious names but clearly recognizable.

The poisoner poisoned

Perhaps the most spine-chilling episode is her confession to poisoning her grandfather, who she drew while he lie expiring. Confronted with the choice of following her family’s long line of suicides, Salomon could have easily taken the poison herself. Instead, she chose a different path: she served him the poison and watched him die before writing a letter confessing to the deed. Salomon didn’t kill him to save him from deportation to the camps; she murdered him to finally be rid of her abuser.

An unfathomable legacy

Salomon entered a loveless marriage and was expecting a child in 1943 when she entrusted her life’s work to a friend, saying ‘Keep this safe. It is my whole life’. Shortly after this, she was apprehended by the Gestapo, transported to Auschwitz, and immediately sent to the gas chamber where she and her unborn baby died. Her husband suffered the same fate a few months later. After the war, Salomon’s work made its way to her father, who survived the war by hiding in Amsterdam with his wife. He didn’t know quite what to make of Salomon’s complex, entangled creation.

Salomon’s father and stepmother took the paintings back to Amsterdam and didn’t look at them for years. Salomon’s gesamtkunstwerk or ‘total work of art’ has since been the subject of exhibitions, featured on the Jewish Historical Museum site, and has inspired a novel and a ballet.

Duckworth will publish a new-cased hardback edition of Life? Or Theatre?, and it will be available in English for the first time in September 2017 to mark the centenary of the artist’s birth.