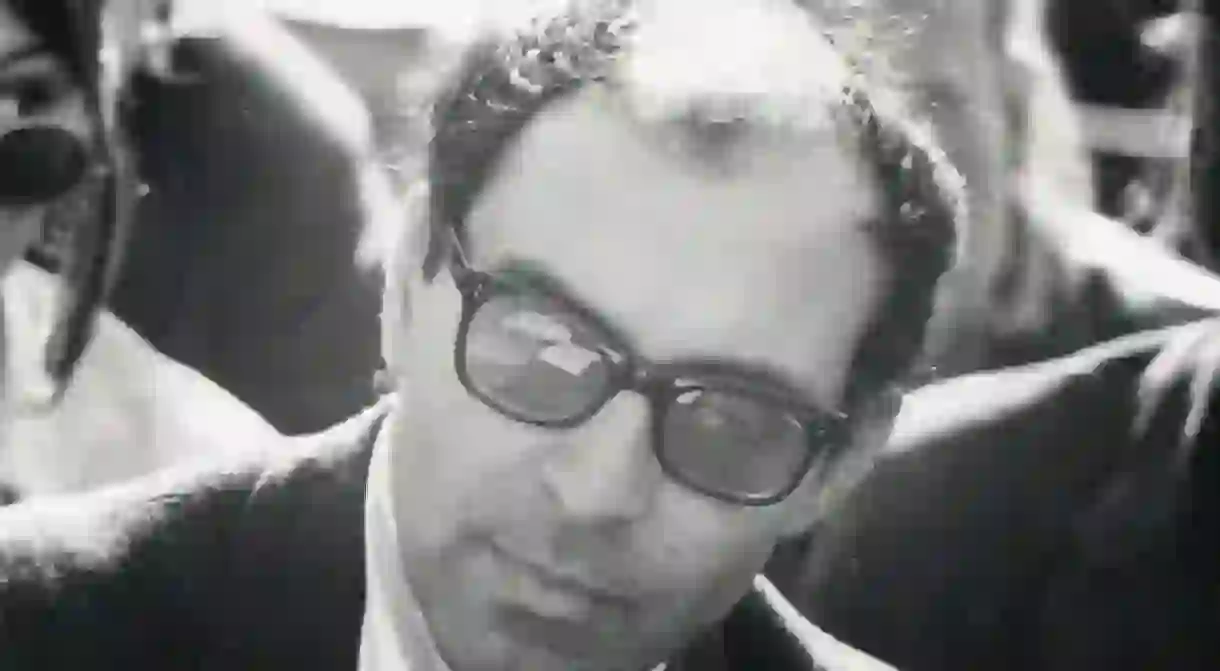

Jean-Luc Godard's Magnificent Seven

The most famous director to emerge from the French New Wave, Jean-Luc Godard was at the helm of a movement that rewrote the very language of cinema itself. We examine the stylistic and thematic contributions of this revolutionary auteur in a journey through his career and landmark films.

Post-war European cinema witnessed a different kind of battle to the one that had ravaged the continent during the preceding decade; with the military conflicts drawing to a close, there arose instead a clash of cultures. It was out with the old and in with the new, as a young, fresh generation of directors rose up, reacting against the stylistic and thematic conventions that had previously dictated the film landscape. Nowhere was this more perfectly captured than in the cinema of the nouvelle vague – the French New Wave – and the films of Jean-Luc Godard.

The New Wave was hardly alone in its re-imagining of European cinema. With the exception of Germany, the film industries of Europe had fully recovered by the 1950s from the strain of the war, and a new phenomenon popularly known as “art-house cinema” was emerging across the continent. Among the popular aesthetic movements in Europe during this time was Italian neo-realism, which rejected studio shooting, the use of stars, overt glamour, and grand narratives – all traits that were to exert a powerful influence on the New Wave directors.

Inspired in part by the sudden influx of Hollywood films following the end of the war-time cultural blockade, the films of the New Wave were truly revolutionary, in both content and form. Beginning their film careers on the pages of the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma – founded by the hugely influential critic and theorist, André Bazin – the New Wave directors developed a collective, reactive cinematic aesthetic long before they took up their cameras.

Their unique style was to have an immeasurable impact on modern cinema, one that continues to this day. Directors like Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut were the first to experiment with this new revolutionary style, but it was Godard who achieved international attention and commercial success with his ground-breaking debut, Breathless (A bout de Soufflé, 1960). The movie catapulted the movement to the foreground of European cinema.

“Photography is truth. The cinema is truth 24 times per second” – Jean-Luc Godard

Godard was born in 1930 of Franco-Swiss descent and spent his childhood years between Switzerland and France. He was an anthropology student at the University of Sorbonne but did not attend classes much. He was first drawn to cinema by a reading of the essay “Outline of a Psychology of Cinema”, and La Revue du cinéma, which was re-launched in 1946.

Godard got deeply involved in the film societies of the Latin Quarter in Paris, like the Cinémathèque, the CCQL, and Culture Ciné Club toward the end of the 1940s. At these film societies and clubs he met fellow film enthusiasts and critics like Chabrol, Truffaut, and Jacques Rivette.

Godard said of this time, “We watched silent films in the era of talkies. We dreamed about film. We were like Christians in the catacombs.” He was the first of the young critics to be published. His “Defense and Illustration of Classical Découpage,” published in 1952, in which he criticizes an earlier publication by Bazin and defends the use of “shot-reverse shot technique”, is one of his most significant early contributions to cinema.

In the early 1950s he concentrated mainly on his work as a critic for Cahiers and helped his friend and editor, Éric Rohmer on “Présentation ou Charlotte et son steak”. In the late 1950s he made short films and collaborated with other directors like Truffaut. He burst onto the scene in 1960 with his first feature, Breathless, commencing the period between 1960-67 that was the most productive and important of his career.

Godard has reinvented himself dozens of times over a career spanning more than half a century and is still going strong. Below is a closer look at seven of his famous films from his productive early period.

Breathless (1960)

This was the film that changed the face of cinema forever. It is an unpolished masterpiece, a risqué deconstruction of the conventions of cinematic storytelling, that broke every rule in the book. Breathless is the story of a hoodlum, Michel Poiccard, who steals a car, kills a police officer, goes into hiding in Paris, and eventually attempts to escape with his young American lover, Patricia Franchini. Godard used no real script, shot without permits using hand-held cameras, used mostly natural lighting and, above all, showed a complete disregard for the classical style of continuity editing. His effervescent young actors, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, were allowed to wear clothes that they felt comfortable in, and used little makeup. The effect was fresh and invigorating.

Godard’s excessive use of jump-cuts and non-conventional styles of editing captured the spirit of post-war Paris: an overwhelming sense of freedom, an obsession with modernity, a dismissal of authority, and detachment from conventional moral frameworks. Intensely Parisian though it may be, the influence of film noir on Godard’s is also made explicit; iconic American posters can be seen splashed on the walls in several scenes; his protagonist Michel nurses a borderline infatuation with Humphrey Bogart, unashamedly emulating the mannerisms for which the star is so well known; crowds can be seen cheering for President Eisenhower during his visit to France. The intertextuality is rich and flagrant, but Breathless has a magic all of its own.

A Woman Is a Woman (1961)

In this film, Godard flirts with the American musical style, delivering a playful tribute but with his usual intellectual sarcasm. Featuring Anna Karina, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Jean-Claude Brialy at their peak of popularity, it is endearing and funny and uses the vibrant music of the renowned composer Michel Legrand. It tells the story of a love triangle between an exotic dancer, her lover, and his best friend, and it flirts with gender politics and questions of female identity, though in an admittedly androcentric manner. This is Godard’s most light-hearted work and Anna Karina is a delight to watch.

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This is one of Godard’s landmark films, a dynamic and poignantly tragic character-study. It is also the most accessible of all his films, with a haunting, recurring theme and beautiful visual design. Anna Karina plays a young Parisian with starry-eyed dreams of being an actress who makes poor life choices, ending up as a prostitute. It is Karina’s best performance; the film is a timeless tale, an exploration of expression in a detached society.

Contempt (1963)

Godard’s first venture into commercial filmmaking, this is a star-studded drama with big-budget backing and Brigitte Bardot setting the screen on fire. Contempt stars Michel Piccoli as a screenwriter torn between the demands of a proud European director, an arrogant American producer, and his disillusioned wife, Camille (Bardot). This is a brilliant study of a fragile marriage falling apart under pressure. Breathtakingly shot in CinemaScope and technicolor, Contempt is visually stunning with elegant tracking shots and beautiful red tones in every frame, an example of Godard’s obsession with the color.

Band of Outsiders (1964)

A second and more radical gangster themed movie, Band of Outsiders is a story of two young men and their common love for Anna Karina, who helps them to commit a robbery. It is an extremely entertaining story, effervescent, youthful, and charming. It features some of the most memorable scenes from Godard’s films – a race through the Louvre and a very cool Madison dance sequence.

Pierrot le fou (1965)

Pierrot le fou is a gem of the French new wave. Starring Godard’s Breathless lead Belmondo and Anna Karina, the director’s wife and muse, the film is a stylish, satirical, romantic road movie with an explosive finale. It is the story of a man who is frustrated with his life and marriage and decides to go on a trip with his ex-lover and babysitter. In casually breaking the “fourth wall”, acknowledging the audience, and shattering the illusory nature of cinema in a memorable car scene, Godard made Pierrot le fou the perfect New Wave rule-breaker.

Weekend (1967)

Weekend is a chilling satire – a black comedy that portrays a society that is selfish, consumption-oriented, and greedy. Godard’s Marxist voice rings loud through the narrative as we follow a young couple traveling through the French countryside to get an inheritance from a dying relative. The film features a very famous tracking shot through a traffic jam.