How 19th-Century French Artists Thought The New Millennium Would Be

Predicting the future is a fickle business, no matter how blithely fortune tellers and city traders go about it. Over a century ago, a group of French illustrators was tasked with imagining what technology would look like in the year 2000. Their ideas weren’t always on the money (how we wish whale-buses, seahorse-polo, and barracuda-quidditch were things) but many have been realized albeit not exactly according to the original drawings.

Jules Verne and the 19th-Century Imagination

If you had to guess the artist that imagined bonneted tourists cruising around the ocean depths in a tram car strapped to the belly of a humpback whale, you’d be forgiven for suspecting one of the San Franciscan members of the 1960s psychedelic art movement like Rick Griffin or Alton Kelley, or maybe even Salvador Dali in his interwar clock-melting days. Then again, the brutality of the 20th century’s world wars does tend to make us forget the optimism and vitality of the preceding Belle Époque.

This was an age when copies of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires, a series of 55 novels written between 1863 and 1905, were on bookshelves in homes up and down France and, despite some shoddy translation work, in households across the English-speaking world, too. Considered still the grandfather of science fiction, Verne fed the public imagination with sensational technological inventions that the age of science seemed to be bringing into the realm of possibility. To an audience not just familiar but obsessed with a story like that of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1869-70), the prospect of a whale-bus, or a life lived under the waves in a myriad of other ways, probably didn’t seem that far-fetched at all.

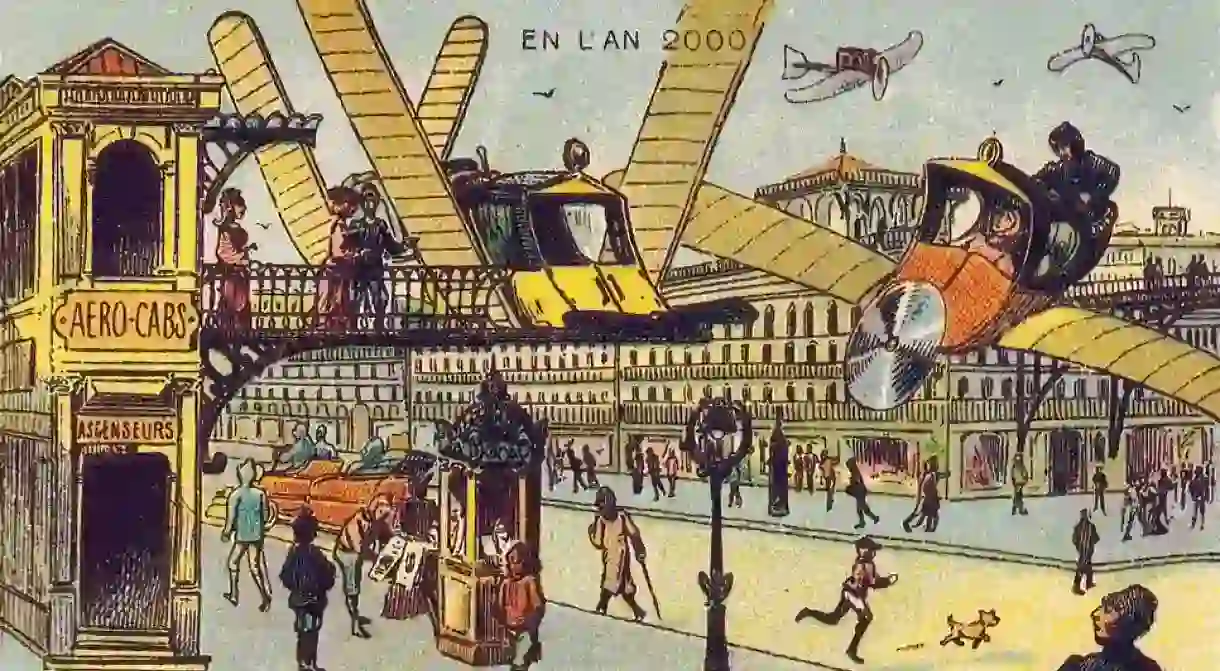

The Origins of ‘En L’An 2000’

No one’s quite sure exactly how the En L’An 2000 image series, which is translated both literally as In the Year 2000 and loosely as France in the 21st Century, came about. Some believe it was the pet project of a toy maker while others attribute its development to a now-defunct tobacco company. In any case, the 87 illustrations were created first in small format, capable of being inserted into a cigarette packet, and later as postcards, though these were never widely distributed.

Though numerous artists are thought to have contributed to the collection, Jean-Marc Côté is the name most often associated with those published in 1899, 1900 (the year in which they were displayed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris), and 1901 and Villemard with those that appeared in 1910. In any event, they were all forgotten for the better part of a century until the American science fiction writer Isaac Asimov stumbled across a preserved set of them, which he later published in his 1986 book Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000.

Which predictions have come true and which haven’t (yet)?

If you can look past all the levers and pulleys (which, along with propellers, dominate most of the illustrators’ designs), it’s not difficult to discern modern-day cleaning robots like the Roomba in a postcard of an electric scrubbing device.

While you’d be hard pushed to find quite such a frilly maid’s uniform in a Paris hotel these days – which isn’t to say you wouldn’t have luck in some of the velvet curtained stores up in Pigalle – the getup of flat cap, waistcoat, puffy shirt, and culottes has persisted out in the rural provinces. (Okay, maybe not the culottes, sadly.) What is undeniable about farm life in France and elsewhere, however, is the rapid, job-robbing rise of mechanization over the past 100 years.

Another premonition which has (unfortunately) come true is that of the mobile home. Admittedly, Côté’s rolling villa – with its pinstripe awnings and observation deck – is quite a bit more elegant than the road-hoggers we 21st-century road users have to put up with, but the idea was bang on.

Obviously, even though major strides (or, more accurately, leaps) have been made in the field of human flight we are still some way off having airborne postal workers. However, at the end of 2016, residents and businesses in the Var département in south eastern France became the first anywhere in the world to receive mail by drone on a regular commercial route.

Schoolwork may still be a metaphorical grind for most of today’s children but this illustration does contain the nuclei of the ideas behind audiobooks and digitized information generally. We may not yet be able to download information directly into our brains but if the makers of the Matrix can dream it then surely there’s an inventor out there who can make it a reality.

What can we learn by looking at the past’s future today?

According to Tom Standage of The Economist, writing in an introductory chapter of the 2017 book Megatech: Technology in 2050, technological innovation comes about thanks to a combination of the past – the insights offered by reactions to similar inventions in previous eras – the present – the acceptance of a product in one specific market prior to a global rollout – and the future – the incredible things that science fiction writers are able to dream up and explore the implications of in the controlled setting of an imaginary world. So, even if the wildest of these 19th-century drawings (more of which can be viewed on Wikimedia Commons) don’t provide a blueprint for success, it never hurts to look back when trying to think of the next big thing.

But, before you scurry off into your basement laboratories to work on your game-changing invention, take some time to reflect on the far-from-complex ideas that society is taking far too long to implement. Case in point: equal pay.