Carrying the Weight of Genocide Through Photography

At first glance, The Blue Skies Project seems to be an artful contemplation of atmospheric serenity. Helmed by Belgian photographer Anton Kusters, the photographic venture is a profound curation of over 1,000 Polaroid images bearing fair weather and corresponding coordinates; but beneath each of those fine blue skies, innumerable atrocities have taken place.

The Blue Skies Project embodies Kusters’s personal quest to preserve memory of the Holocaust: an abominable stain on human history that is rapidly evanescing with time. The assemblage is comprised of 1,078 images, photographed between 2012 and 2017 at the precise locations in which “that genocidal act” was carried out. Despite their pleasant outward appearance, each of these silent skies has played witness to the unspeakable events that unfolded below.

“Like all of my projects, Blue Skies was personal,” Kusters told Culture Trip. “I became aware, in 2012, that the Holocaust had literally brushed past the door of my family.”

Kusters’s grandfather—a Belgian national who was not Jewish, nor is he thought to have been part of the resistance—was one of five villagers for whom the SS mysteriously embarked on a mission to seize and deport. In 1943, Hitler’s paramilitary army stormed his town and knocked down his door, but “through a miracle of circumstance,” as Kusters put it, he managed to escape and was never found—though he spent the remainder of the war in hiding. Kusters’s grandfather died in 2007, and having uncovered fragments of his story posthumously, the photographer never got the chance to ask him, why?

“The only thing I could do was imagine what would have happened if they had taken him,” Kusters explained. “Where would he have gone? What would he have seen?” Without the possibility of answers from the source, Kusters set out on his own mission: through art, he would resurrect the millions of Holocaust narratives lost to time.

Thus, The Blue Skies Project began on March 6, 2012 at Auschwitz in Poland, one of the largest and most infamous sites of human annihilation in history. There, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, approximately 1.1 million prisoners were massacred between 1940 and 1945.

The project became Kusters’s effort to understand the repercussions of trauma. He visited every concentration camp of that “industrialized genocidal system” in Europe, and photographed the skies above each site where so many victims perished en masse.

“Visiting these places was my way of trying to understand [the Holocaust],” Kusters said. “It’s so important to engage with collective memory. If everyone starts forgetting, no one will believe that it ever even happened.”

And that’s a plausible danger that future generations face. In February 2018, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany commissioned Schoen Consulting to interview 1,350 American adults aged 18 and over for a study coinciding with Holocaust Memorial Day. Their research yielded a disturbing conclusion: that two-thirds of American millennials are unaware of what Auschwitz is, while 22 percent of American millennials have never—or, at the very least, are unsure of whether they have—even heard of the Holocaust.

Kusters hopes that The Blue Skies Project will provoke a renewed awareness of this still-recent cataclysm, and combat the risk of erasing it from collective memory. But the danger of forgetting is one that follows all landmark events, and Kusters nods to the frailty of remembrance through his decided use of Polaroids.

“The Polaroid, in and of itself, is deficient in that you need to take care of it—otherwise, it fades,” he noted. “The use of Polaroids is strongly connected to the fading of collective memory. All of these Polaroids are fragile. They require the intervention of curators or whoever possesses the work to keep it safe.”

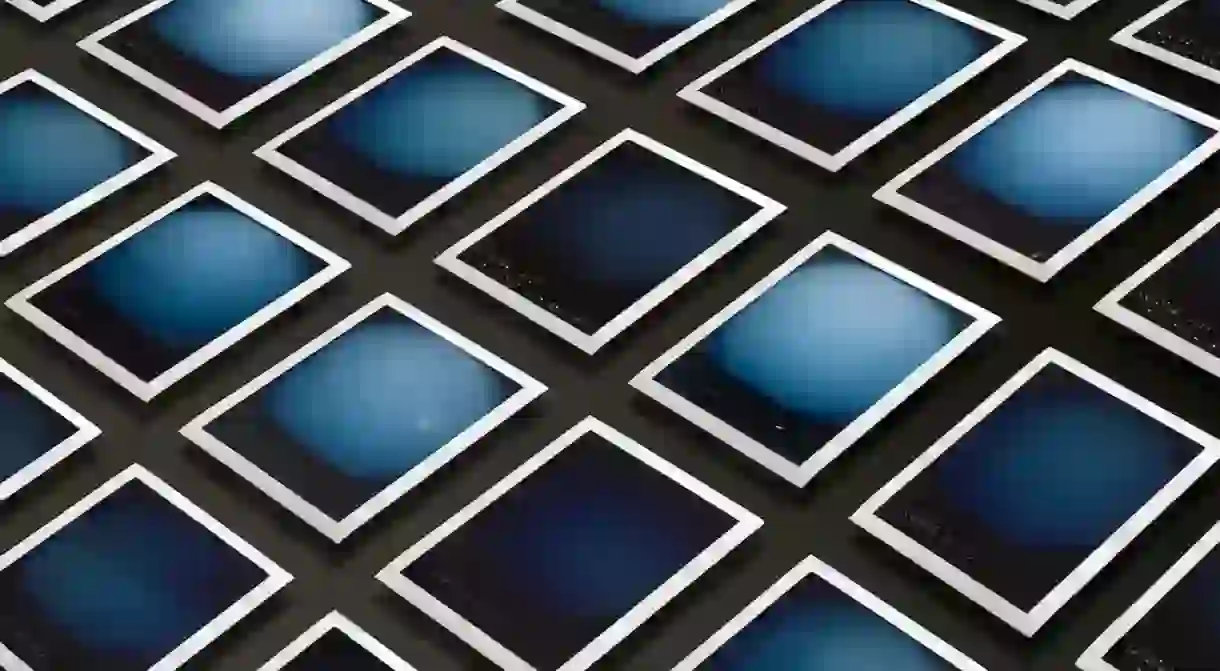

Assembled in a neat grid, the Polaroids literally reflect the viewer in their glossy sheen so that visitors become a temporal part of the installation. “The photographs bring the past in front of you,” Kusters said, “and you’re suddenly confronted with something you don’t really understand. Nowhere is it explicitly stated that the project is about the Holocaust, but you slowly find out.”

In its exhibited state, The Blue Skies Project is accompanied by a sound installation designed by Ruben Samama. “I met Ruben when I was three years into the project, but by luck, I happened to be in Tokyo and meet him on the other side of the world,” Kusters recalled. And the project’s aural component—a soundtrack, computer-generated by Holocaust data—rivals Kusters’s photographic assemblage in poignancy. It’s an independent, autonomous piece, Kusters says, but when conjoined with the photographs, both elements become one immersive, all-encompassing work of art.

“Samama’s audio piece is 13 years long. It mimics the period of time between the opening of the first concentration camp and the closing of the last, which was about 13 years from 1933 to 1945,” Kusters informed. “It’s played live, and every time a sound is generated, it represents a victim. You can literally re-live, in audio format, this entire period of trauma that was the Holocaust. You’ll hear a ‘ping,’ and then another a few seconds later. You might hear two at the same time. It becomes really personal because suddenly it could be your father or your wife or your children.”

The truth is, Kusters argues, that most contemporary viewers will be simply unable to fathom the extent of this trauma—himself included. “It was impossible to reminisce upon the full extent of what happened in each place,” Kusters said of visiting the concentration camps. “I would never be able to complete the project.”

As it stands, the project is still incomplete. Its first formal presentation was held at New York City’s International Center of Photography in mid-April 2018; and while he made his “final journey” in September of last year, Kusters considers Blue Skies very much ongoing. For starters, he plans to release a colossal, 2,200-page book with Lars Müller Publishers in Switzerland this autumn. “It’s a small book in size, but [the seriousness of the content] is a huge, senseless thing. This book is my way of asking the reader to help carry the weight of what’s happened.”

In addition to the book, which is slated for distribution in September/October 2018, Kusters is developing an open-source app. “The data is open-source, so another artist could create something completely new with the numbers. And because the app is open-source, you could use it to chart another trauma,” he said, offering the example of police brutality victims in the United States. “It could be adapted to show blue skies above any location, and bring that trauma to the attention of the people.”

A series of exhibitions are also on the horizon. Kusters hopes to house the original Polaroids in one museum’s collection so that reproductions can travel to institutions around the world. Negotiations for both the permanent installation and traveling shows are currently in the works.

When asked how he’ll know when the project is finally done, he replied, “I don’t know! I think I will feel that I’m done when I feel that enough people are carrying this weight with me. Memory can’t exist by petrifying it like a statue. It can only exist by allowing the next generation to talk about it, to engage with it, and to see it in their own way. We have to entrust it to them. That aspect of the work is the most important part.”

Purchasing a Polaroid is another way for the world to share this “weight.” At each concentration camp, Kusters created three images: one is included in the installation, one is placed in storage for safekeeping, and one is framed for global distribution.

“You have two maps,” he said. “You have the original map of trauma where the concentration camps were built, and now, you have a new map of people all over the world who buy a single Polaroid to keep the story alive. This is a positive map of hope. I suppose I have to continue this project until all of the Polaroids find a new home.”

The International Center of Photography is the first institution to purchase a Polaroid. Following the project’s inaugural presentation, the director stood up in the audience and said, “We don’t want you to carry this alone. We take responsibility to carry it forward with you.”

Kusters hopes this project will remind the world to think of the victims’ lives, their stories, and their fates when we look up at blue skies overhead.