Explainer: Why the Director of Oldboy Has Been Banned from State Art Funding

Amid South Korea’s presidential scandal, involving numerous cases of corruption, lies and other various controversies, new evidence concerning a government-backed artist blacklist has surfaced. Read on to learn more about the reasons behind the list, and the repercussions it has had for both the artists on the list and the government officials who created it.

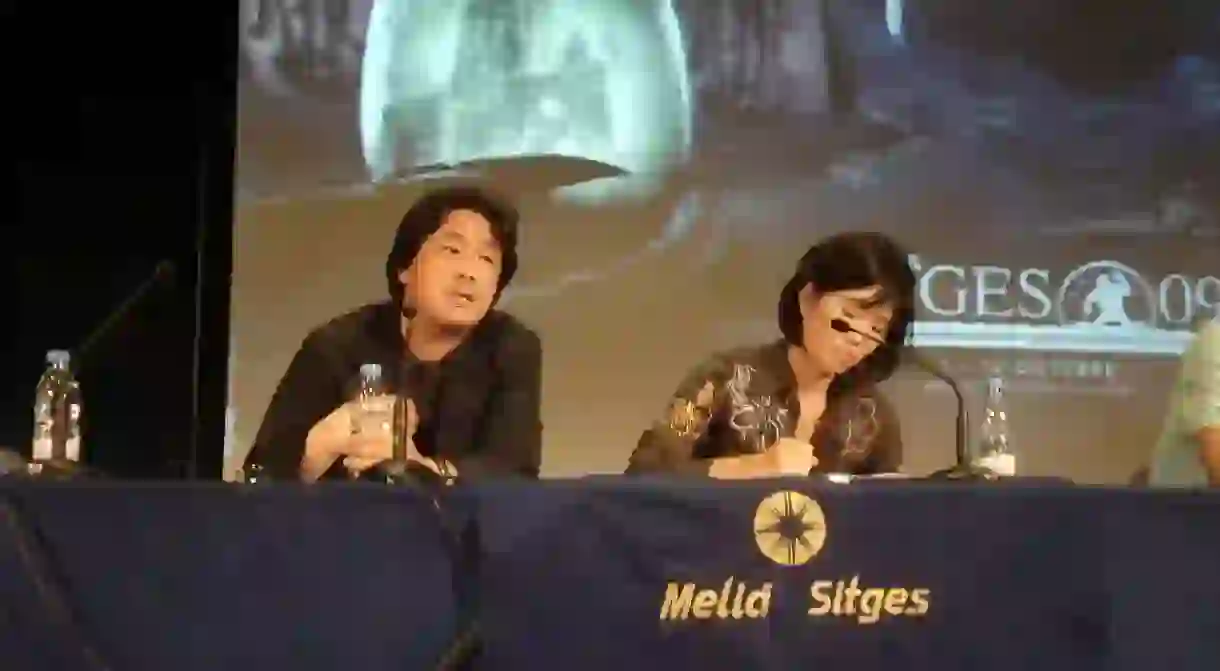

Park Chan-wook is without a doubt South Korea’s most celebrated film director. His controversial 2003 hit Oldboy made waves across the globe, landing some 35 awards at the world’s top film festivals and recognition ceremonies. More recently, his film The Handmaiden became the most internationally acclaimed Korean film of 2016. Despite this, Park is among those on just-impeached, South Korean president Park Geun-hye’s blacklist of artists who have been banned from receiving financial and logistical support from the government.

Park is not alone. In fact, he is among some 10,000 Korean directors, actors, artists, authors, musicians and publishers on a supposed blacklist of creatives critical of President Park.

Recently discovered evidence of the list is yet another twist in a shocking scandal that has both shaken the nation, and led to Park’s impeachment.

In January 2017, a prosecutor investigating the scandal arrested Kim Ki-choon, Park’s former chief of staff, and Culture Minister Cho Yoon-sun on suspicion of abusing their positions by imposing the blacklist.

President Park refutes any involvement and recently sued a reporter at the Joongang Ilbo, a Korean newspaper, for stating that she ordered the creation of the blacklist in response to intensifying criticism following the mismanaged rescue of the Sewol, a ferry that sank in 2014, killing hundreds of citizens, mostly high school students.

Following the recent arrests of Kim and Cho, the blacklisted artists claim that the Korean Film Council Director Kim Se-hoon and former Busan Film Festival chairman Suh Byung-soo should also be condemned. In fact, more than 1,000 South Korean filmmakers have already come forward to sign a petition demanding the expulsion of the two, who are said to have endorsed the government blacklist.

In October 2014, Suh attempted to unsuccessfully prevent the Busan Film Festival from screening The Truth Shall Not Sink With Sewol, a controversial documentary about the sinking of the ferry. Filmmakers denounced Suh’s censorship attempt, while festival organizers assert that they were subjected to extreme funding cuts and unprecedented audit reviews following the premiere of the documentary. Recent evidence shows that these orders came directly from President Park’s office.

In the following year, the government halted support for theaters showing independent films, instead granting the funds to those screening movies endorsed by a state-financed council, including recent patriotic blockbusters.

In response to growing opposition and protests fueled by their actions, the culture ministry earlier this month pledged 8.5 billion won (approximately $7.3 million) to support art projects that had been halted by the blacklisting.

The ministry also announced that it would move forward with legislation to safeguard artists’ freedom of expression and protect them from political censorship going forward. Authorities are also planning to allow artists to elect the heads of state-supported arts organizations – positions that had previously only been assigned by the ministry.