This Virtual Museum Allows Armchair Travellers to Explore Nepal

The innovative Global Nepali Museum connects Nepalese people with their heritage and helps travellers confined to their homes because of the Covid-19 pandemic to experience the country through its art, culture and history.

In a beautiful pencil sketch entitled Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, the focal point of the old city is frozen in time, buzzing with activity. Street traders tout their wares in the shadow of a classic Nepali three-storey temple. Nearby groups of locals huddle together for a chat, while a cook sits crossed-legged in front of a smoking fire, rotating kebabs above the flames. In the foreground, a pair of elderly women with large, heavily laden wicker baskets strapped to their backs slowly make their way to market.

To the west, just out of view, is Kumari Chowk, home of a young girl who is worshipped as a living goddess. If you click onto another page a chunky V-shaped gold necklace with turquoise gemstones, once worn by the Kumari herself, will appear. After scrolling through a series of photos, viewing the artefact from all angles, you can move onto a fresh page. A colourful, 15th-century mandala (a geometric Buddhist meditation aid) might pop into view, or a tiny silver amulet dating back to the early-19th century, or even a fearsome shamanic mask.

A museum in the cloud

The Durbar Square sketch, the Kumari’s necklace and all the other items can be viewed in the Global Nepali Museum, wherever you are in the world. Launched in January 2019, the website of this innovative virtual museum – or, to quote its founders, museum in the cloud – has a collection of more than 3,000 Nepali items, all of them owned by overseas museums and galleries. They include sculptures, statues, icons, paintings, drawings, books and manuscripts, as well as rare cultural objects such as ritual daggers, rice bowls and oil lamps.

For each exhibit, there are high-resolution photos and panels with contextual information, as you would find in a physical museum. Unlike a physical museum, though, there are no crowds to wade through. It is easy to get a close-up view, you can stay as long as you like, and there’s no entry fee.

The Global Nepali Museum is a response to the fact that many of Nepal’s finest artworks and artefacts are held overseas and, as a result, out of the reach of ordinary Nepalese people, explains co-founder Roshan Mishra. “I thought it would be a good idea to create a virtual museum where the Nepalese people could go and find out about what we don’t have – our artefacts displayed in different museums around the world,” he says via Skype from Kathmandu.

Illegal art trafficking

One of the main reasons why so much of Nepal’s cultural heritage is now outside of the country is illegal trafficking. Nepali law prohibits the buying, selling or trading of objects aged 100 years or more, but is routinely flouted. According to the 2018 Al Jazeera documentary, Nepal: The Great Plunder: “Since the 1980s, [Nepali] authorities estimate thieves have plundered tens of thousands of Nepalese antiquities. About 80 percent of the countries religious artefacts have been stolen and sold into the $8bn-a-year illegal black market in art.”

Temples, monasteries and shrines are often broken into – sometimes with the connivance of their supposed safe-keepers – and antiquities stolen and then spirited out of the country through unscrupulous traders, before being sold for huge profits on the black market. “Many of our cultural objects are very easy to transport: most Nepali objects in collections around the world are less than 3ft (0.9m) – they can go in a suitcase,” explains Mishra, who is also director of the Taragaon, an architectural museum in Kathmandu.

Few of Nepal’s historic sites have detailed inventories of their artefacts, so it is difficult to keep track of what has been taken. In any case, government monitoring and enforcement is ineffective, says Mishra. Once they are out of the country, objects are even harder to track down, not least because many museums, galleries, art dealers and auction houses are decidedly opaque about the source of the items in their collections and catalogues.

Mishra believes that the Global Nepali Museum could make the process easier. “When you have this huge database [on the museum’s website] it is easier to track where objects came from and how they travelled from Nepal.” But he emphasises that he is not calling for a repatriation campaign. “If someone wants to use [the museum] to do a repatriation campaign, that’s up to them. From my position, I probably wouldn’t do that. For me, in certain ways, it’s good to have Nepal represented in lots of different countries. Otherwise, Nepal might not be known at all.”

A virtual trip around Nepal

As well as connecting Nepalese people with aspects of their lost heritage, the Global Nepali Museum also allows armchair travellers unable to visit Nepal in person to do so digitally through its art, culture and history. Mishra recommends starting a virtual trip around Nepal in the Exhibitions section of the museum. “At the moment, we have the Hodgson collection of drawings by artist Raj Man Singh Chitrakar, produced in the 1840s,” he says. “It’s a very significant collection that is owned by the Royal Asiatic Society in London.”

These evocative pencil sketches depict the key historic, religious and political sites in the Kathmandu Valley, some of which have changed remarkably little over the last 180 years, as well as scenes from everyday life. In one sketch, lines of pilgrims make their way along the gently curving banks of the Bagmati River to the Pashupati Temple, the holiest Hindu site in Nepal. In another, a group of villagers toil in a network of rice paddies, with the ancient city of Patan rising in the distance. A third sketch focuses on the elegant golden gate and finely carved latticed windows of the vast Royal Palace in Bhaktapur, an architecturally rich Newari city.

Mishra also directs armchair travellers to some of his favourite exhibits in the museum, a group of gold, triple-tiered, jewel-encrusted crowns dating back to the 13th century and once worn by Buddhist Vajracharya – Master of the Thunderbolt – priests. “They’re now in the British Museum in London and the Rubin Museum of Art in New York,” he says. “They’re the most fascinating objects.”

Although you can explore the museum thematically, it is generally more rewarding to hopscotch randomly from one exhibit to the next and see where you end up. The crowns of the Vajracharya priests might lead you to a 15th-century painting of Swayambhu, the great hilltop Buddhist stupa (domed temple) that overlooks Kathmandu. From here, you could stumble upon a bright, parrot-filled painting from the lowland Terai region, before ending up on a conch shell decorated with an image of the Hindu god Vishnu.

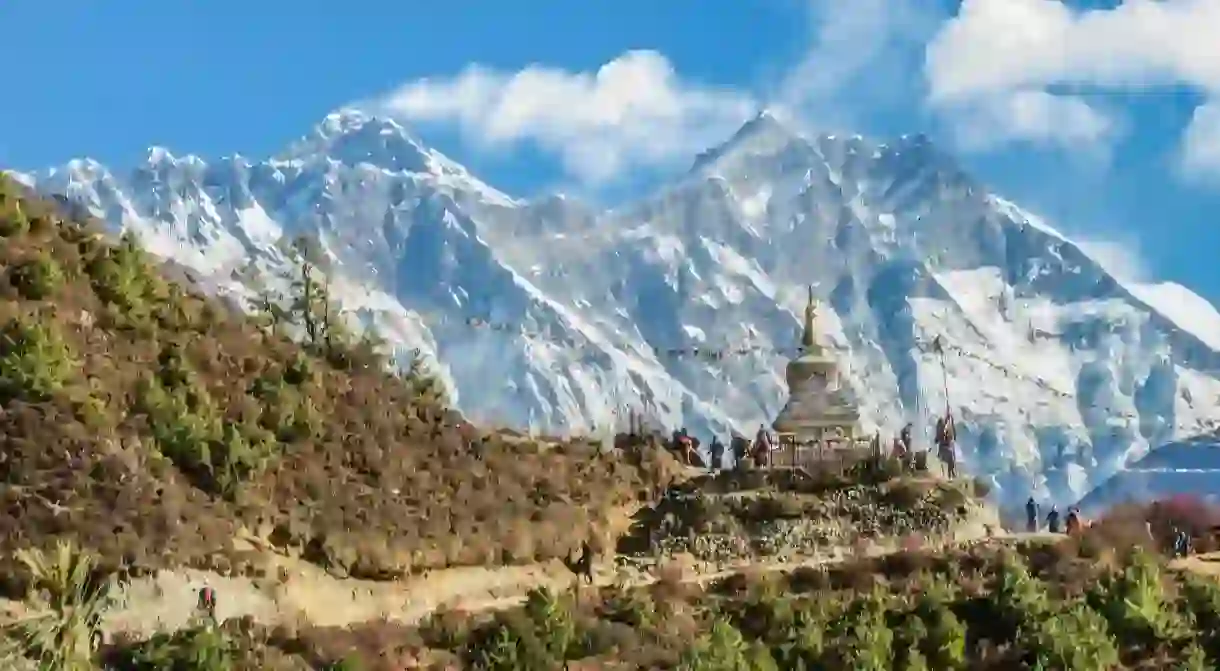

Although physical travel remains a tricky prospect for many, the Global Nepali Museum can transport you, if only for a brief period, from your home to the foothills of the Himalayas.