A Look Inside Beirut's Art Scene

In between political violence, economic struggle, and geographical distance from the world’s major art centers, Beirut’s creative scene is complex and ambivalent. We take a closer look at the Lebanese capital’s art scene.

Of course Beirut is not London or New York, and although it does have that colonial twisted identity as the Paris of the Middle East, it isn’t like Paris at all. French is spoken along with Arabic and English, interchangeably and with no discernable logic (some words are just spoken in French others in Arabic). Along with, but unlike, the Lebanese multilingualism, there is also an intense sectarianism: religions do co-exist, but always, it seems, on the brink of some kind of turmoil. While the long and painful civil war is still in fresh memory, flashback car bombs and sectarian violence keep these memories alive, the air tense and the city militarised if not mildly panicked.

So, despite the wonderful hospitality of the Lebanese, Beirut is hardly a welcoming city, and it takes a certain madness or courageousness to spend time there, especially as a tourist (threat of kidnap included). However, as an artist, somehow these conditions, threats and these histories are fecund ores for creativity. The city is culturally stimulating, intelligent and most of all deeply politicised. In this, creative context, politics is life breath – unavoidably so.

As an American art tourist it is hard not to make comparisons to Los Angeles, my home most of the time. If Beirut breathes politics, even if it is by way of sectarianism, then LA breathes the oxygenated perfume of amnesia: depoliticised, de-historicised foam that comes on top of seven-dollar almond milk lattes. The artworks produced in each place reflect their socio-cultural conditions: LA art is to celebrity frivolity and blue-sky plasticity what Beirut is to historical analysis and a politics of media-forms. This is to say simply that American art is out of touch, or America is out of touch, despite its foreign policy, which affects so much of this region.

To begin to understand this complex relation, try to imagine the feeling in LA if, by some twist of power an aerial attack on San Francisco was announced (the distances are comparable distance to those from Damascus to Beirut). The ‘good-life’ or the drive for the ‘good-life’ necessitates such being ‘out-of-touchnness’ – it is, of course, hard to enjoy one’s latte if one is all too aware that the coffee beans have (literally) had blood on them.

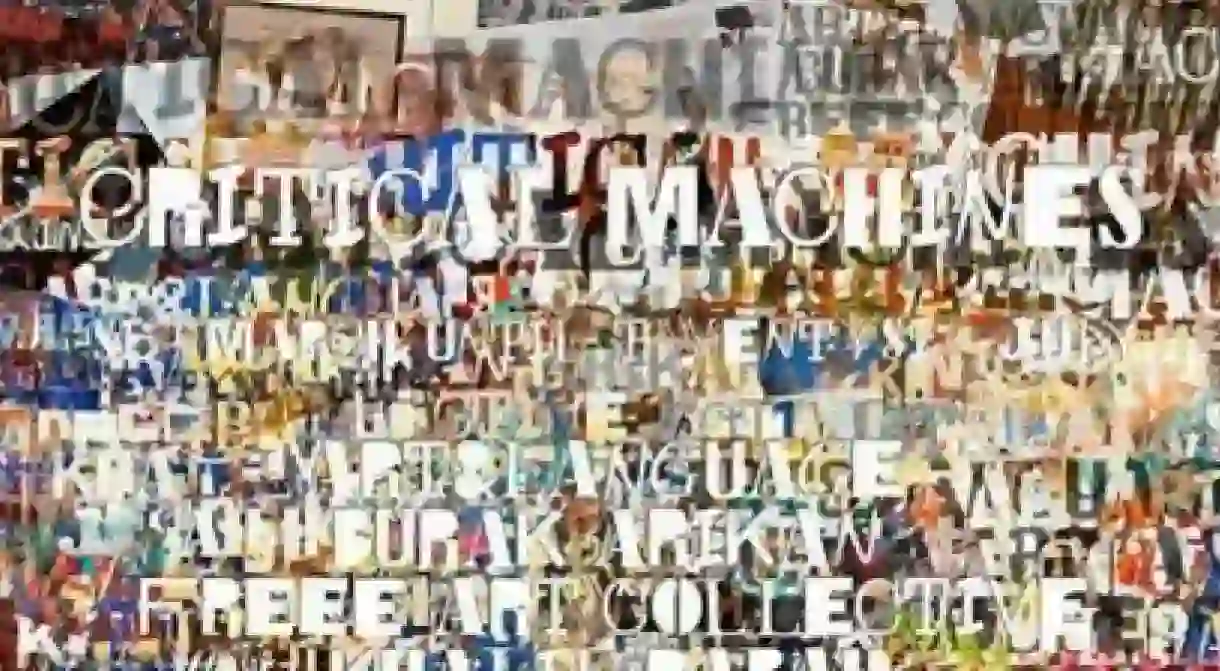

This dichotomy, between the American (or even Western art world) and parts of the Middle East (or even developing world) was brought into extreme focus during a conference at the American University of Beirut; half of whose buildings have been constructed by the US State Department – a possible hotbed for spy breeding? The conference was part of an exhibition titled Critical Machines: Art Periodicals Today – in which a selection of art journals from around the world were invited to critique themselves – in the context of the contemporary bankruptcy of critique as a politico-aesthetic strategy.

At the beginning of the conference Octavian Esanu, the curator showed an example of the way critical theory was being re-deployed in managerial manuals for corporate organisations. The last panel was perhaps the most interesting as the Brooklyn-based Cabinet was pitted against Bidouin(a post-colonial initiative based in New York and LA), Al Ahkbar (the culture section of the Lebanese newspaper, for lack of any actual journal), and Gahnama-e-Hunar from Afghanistan. The difference of concerns was most pronounced between the self-described decadence of Cabinet’smission to re-instate curiosity, and the periodical from Afghanistan, which had to go black and white and underground during the all out art-ban under the Taliban Regime.

But to come back to the question of why Beirut is receiving a certain attention from the global discerners of culture (such as Phaidon) – it is certainly not because of its wealth and that abundance of cultural outposts, institutions and publications that keep the New York art world buoyant, let alone sky-rocketing market prices. In fact, Beirut suffers from the opposite – to name the few spaces on two hands, there is 98 Weeks, Mansion, Plan-Bey, Ashkal Alwan, Dawawine, Arab Image Foundation and Beirut Art Centre. There are also a handful of commercial galleries where the more successful ones have outposts in Europe to survive. This is not of course to belittle the cultural infrastructure of Beirut, which technically seems advanced compared to the social infrastructure of daily power cuts and a distinct lack of public transport or postal services.

What does make Beirut a global art centre, or at least a place worth paying attention to, is simply the high quality of art that is being made here, which reflects a high level of discourse and a sophistication of forms and aesthetic strategies. This excelling and concentration of talent is no doubt due to contextual reasons: the dearth of history, or rather: agreed upon history; along with the trauma of the civil war all provided the right conditions for a new-conceptualism in art to be born outside of historical precedence.

In Beirut Alex Israel didn’t learn from Baldessari who didn’t learn from Goddard – rather the post war artists: Walid Raad, Akraam Zaatari; more or less discovered a radical political aesthetic within a vacuum, or at least at quite a far remove from Western 1970s conceptualism that goes back to Duchamp, who is still The Daddy Artist of the West today. And that sheer innovation is dangerous as much as it is exciting, because the critique isn’t inherited and therefore not subject to generational stylisation (think of Alex Israel as a deeply diluted Goddard, and that’s such a generous description at best).

Of course the post-war generation of artists that came to prominence in the 1990s in Beirut have created enough of a solid tradition that is slowly turning into a style, both in the Middle East and abroad. Think of photographs with hand written text, or war-images deteriorated through media… That said, there is also enough distance between now and then, that artists working today in such a Lebanese art tradition are finding both new ways to respond to its concerns and forms, as well as beginning their own modes of critique and protest that are more appropriate to the socio-political conditions of today, see Tareq Atoui, Rana Hamedin or Marwa Arsenios.

Without wishing to fetishise a more basic style of living; the socio-political conditions in Beirut are only a taste when compared to more diabolical and desperate situations around the world. Nevertheless, unlike Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq, Beirut currently has the means to disseminate and transform these grave concerns into works of art that capture and communicate the important geo-political as well as ideological questions of our time. Accounting for these, and not slogan-embossed sunglasses or another celebrity performance, should be the mandate and the motivation for an avant-garde art. Despite the failure of the Left in the West and the sad demise of the Occupy movement, there is, for me at least, still a viable resistance emerging from non-Western regions such as Beirut – and these voices, in art, politics, cinema and music, should be paid close attention to.